Architect Christopher Benninger narrates the experiences that moulded his life and shares these learnings from his travels in the Third Edition of the Cyrus Jhabvala Memorial Lecture held in September 2018 at India International Centre, New Delhi.

THE STORIES FROM MY JOURNEY

Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow

Prologue

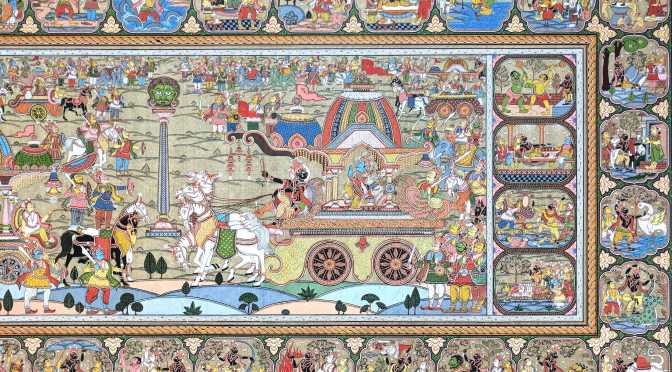

India is the land of storytelling. Since time immemorial oral narratives have been the medium of India’s learning and self-awareness. Oral traditions are kept alive by temple artisans and priests, by wandering minstrels, and dramas in village fairs and tamashas.

Stories can be conveyed through songs, dances, paintings, and of course dramas. Indian stories often share spiritual meanings, but like the Harikatha stories of Andhra Pradesh, they also educate people about ‘self-atma’ through stories showing us paths of liberation. The British and the Nizam banned Burra Katha stories of South India because they used satire and new ideas to raise questions about justice and rational governance. The post-Independence age needed stories of hope and romance, as well as apprehension. The nation needed a vision and a new identity. Pandit Nehru was a great storyteller, uplifting everyone through his stories of hope, and a path into the future, while our present Prime Minister gifts the nation narratives of a better life to come!

The human settlements we have lived in, and the buildings we have lived in, have moulded and tempered the way we think about space, form and urban structure. In a way, these buildings and spaces are stories too. Experiences in urban and built space generate deductive rationality about the way the world is, and gift formative logic about the way the world should be!

These are neither static experiences nor single shot photo images of a context embedded in our thoughts. Rather, these experiences are narratives that have beginnings and endings, openings and closures, even conclusions and lessons. So, there are stories that lie in our subconscious being, stories are drawn from the choreographies of our lives, from the places where we have lived, all telling us who we are, what the world is like and giving us hints of the logic of why things are this way or that. Most of our paintings, dramas, and even our buildings betray autobiographical stories about their authors that moulded their existence and determined their designs. Through these creations, we are searching for the reality of ourselves! Within these stories crafted in built form, and histories laid out in our city plans, we are leaving eternal footprints of our being on this earth.

Architects are very different from other professionals: lawyers fight cases over misdeeds of the past and each case is a story with protagonists; accountants and auditors try to put last year’s figures in an appropriate order, becoming dry prose with only victims; doctors try to save us from our past recklessness, or bad fate, and these become high dramas. But these are stories of the past.

Architects and urban planners are always working in the realm of the future, doing something creative today that will not happen tomorrow, or even next year, or even many years later. Dealing with the future is more uncertain than dealing with the present or past.

Our stories are therefore more complex, messy and even chaotic. They are a journey through the unknown toward an untold destination. So, before I begin to tell you my stories, let me confess that architects write their stories backwards! That is, they begin with the end in mind!

Maybe in telling you my stories, I am telling you narratives of my future, and yours too?

To give you an idea of what I am pondering, let me tell you the first story, that I’ll call Adventure.

Story One

The Story of Adventure

Bringing things into order, finding patterns generic to things, and making templates into which things can be ‘ordered’ are the unique feats of the human brain, driving our strongest emotional compulsions. Yet, this ordering project leads one to something I call the human conclusion, wherein almost all human societies come back to a common set of concerns in an interesting closure of the human condition. To make this short, can I say we all get trapped into the same rites of passage, and the same predictable samskara? In other words: life is a trap.

Perhaps, because of my identity as an ‘outsider’, my life has been a story of escapes seeking alternative meaning systems, and freedom from oppression. Or, perhaps I found middle-class American stereotypes just too mundane and boring to commit myself to.

So, I began a search, even as a child, doing poorly in studies, yet finding myself immersed in art. I found montage paintings more compelling than realistic landscapes. I liked chaos and the secrets of order deep within disarray.

I call people who are on lifelong journeys of self-discovery ‘travellers’, because real travel involves a bit of risk and even danger; it works without foresight, making decisions on the spur of the moment, and asking oneself each morning, “Where should I go today?”

As opposed to a traveller, a tourist seeks a planned schedule of visiting pre-planned sites and events. For the tourists, reservations are a must, always craving safety and predictability. Tourists are buying ‘canned experiences’.

In our daily lives, we are either travellers or tourists. The known is the friend of the tourist, and the unknown is the friend of the traveller. Being a traveller of the spirit, and seeking adventure of the mind, are metaphors of one another.

My first adventures were in playing hooky from primary school. I’d use these escapes to cycle off alone into the wilderness discovering raw nature or walking over to the university student centre, watching abstract art films, which were often very negative, about concentration camps, ethnic cleansing or prostitution. They exposed me to the lives of the oppressed, and I came to know that there was ‘another world’.

In 1963, I travelled from American coast to coast, through Arizona visiting Taliesin West. After an inspiring afternoon, another idea struck me: there was a crazy man in the desert who made bronze bells I’d read about in TIME magazine. Recalling his name was Soleri, I thumbed through the telephone directory, finding a Paolo Soleri, and immediately telephoned him. He answered, “Come right over.”

The next few days were spent exploring in the desert with him, visiting underground shelters, experiencing manmade cave-dwellings, and learning how, in the backyard of his ordinary house, he made bronze bells that sold for thousands of dollars! Years later, he became very famous for ‘Arcosanti’, his utopian city in the desert.

During that visit, Paolo Soleri shared with me the concept I now call, ‘the culture of construction’. He taught me that every building has a place, and each place has its unique materials, climate, craftspeople and construction technology. So, travelling sparks one’s imagination! Travelling knits enriching friendships, and introduces one to gurus, who expose the true personae within oneself; and new possibilities of who you can be. One learns innate truths and concepts that will be carried through a lifetime. These insights are what we call inspiration.

My roommate reached Harvard in 1966, arriving from a 15,000-kilometre bicycle journey around the borders of America, making him my guru of adventure. The next summer we bicycled 1,500 kilometres from Paris to Athens, where I attended the Delos Symposium. We entered countries with no visas and we survived on the hospitality of simple villagers and of friendly small-town people who took an interest in our life’s journey. In the summer of 1967, along the back roads of Yugoslavia, I became a global citizen. I learned of humanity travelling down back roads forbidden to foreigners in a Communist country; everywhere making friends out of strangers. In Athens, and on board Doxiadis’ yacht, I befriended Margaret Mead, Buckminster Fuller, Arnold Toynbee, and my patron, Barbara Ward, and other thought leaders of the 20th century. Ten days in the Aegean Sea, hearing their stories and learning of their worldview, inspired me eventually to settle here in India.

In the afternoons, our small group would explore classical Greek sites. One evening at Samothrace, Professor Toynbee requested me to assist him in climbing up the hill behind the famous ‘Winged Victory’, temple, where he thought an undocumented crusader fort would lie. Sure enough, when we reached the top of this hill his eyes lit up with joy as we saw the ruined walls of an ancient site. Looking to the East I saw a massive black sky, appearing as a mighty thunderstorm headed our way. When I cautioned the professor of the impending deluge, he smiled and said,

“Oh no, that’s just Asia.”

A huge, dark, dust cloud was hovering over Turkey, and little did I know that this symposium sealed my fate to spend my life in Asia. Then the professor said to me, “Go there and you will discover yourself!”

On that day in June 1967 Arnold Toynbee had turned my hazy information into knowledge: he had fixed my sights on the destination of my life! A year later, following Professor Toynbee’s suggestion, I applied for, and won, a Fulbright Fellowship to India.

I travelled around the world to India by plane, visiting Cambodia on the way as the only American visitor who was not in prison! The other 14 Americans were air force pilots, who had been shot down for intruding into Cambodian airspace. Cambodia and America had no diplomatic relations. My comrades in the streets of Nhom Penh were Viet Cong fighters, on breaks from the war in Vietnam.

Another long adventure occurred in 1971, traveling overland to India from London to Mumbai, crossing Europe, Turkey, Iran, Afghanistan and Pakistan, spending eight weeks teaching a studio with Balkrishna Doshi in Ahmedabad, plotting with him to found the new school of planning, and then moving on to Mumbai to meet a man named Charles Correa.

It was the exhilaration of this overland adventure that lured me to India, informing me that this was my new home. One can travel on one’s feet, or travel through reading with one’s eyes. But travel one must! Travel and adventure are catalysts of imagination and friendship. They are creators of self-knowledge and inner awareness.

Story Two

The Story of Compassion

Traditional societies strive for the happiness of the group, while modern societies teach us to be self-sufficient, to succeed, and to strive for happiness through individual achievement. Traditional societies work with compassion as the driving emotion. Advanced societies work for the happiness of the individual, with competition as the driving emotion. Individual ambition, and the innovations it breeds are unique feats of the human brain, driving strong emotional compulsions, known as greed and pride. Regrettably, the resulting ‘success pyramid’ concludes in a counterintuitive outcome: most people are unhappy, while the few successful are lonely!

This ‘competition project’ informs us to brush aside inequality and poverty as obvious human conclusions: perhaps something the government might deal with! ‘Winner takes all’ becomes the closure of the modern human condition.

To make this short, can I say we get trapped into an endless struggle for success, justifying inequality: life is a trap.

When I was a child in Florida we lived in a segregated society where black people sat in the back of buses, and their children attended segregated ‘black schools’. They lived in shanty towns, and whites lived in manicured suburbs. This was a form of institutionalised untouchability.

On a visit to Medellin, Colombia in 1965, where my father was setting up a new school of business administration, I noted that the population was divided into a first city for the rich, and a second city for the poor, whose unplanned, illegal barrios grew up the mountainsides, while the bungalows grew through the valley into distant suburbs along expressways. My economics professor at Harvard, John Kenneth Galbraith, described this to us as a ‘dual economy’, with two alien societies coexisting in the same space, living parasitically off one another.

Walking on the streets of Medellin I noticed young beggars in rags sleeping on the footpaths. One night I observed an amazing thing. Seeing that a boy had no food, another ragged, unshaven man divided his meagre rations, sharing the little he had with his worse-off fellow street dweller. This gesture of compassion filled me with shame, and I felt bound that I must use my skills as an architect to make the world a better place to live. A beggar man become my unsuspected guru in the streets of Medellin!

At Harvard in 1967, Jose Luis Sert gave us a thesis problem to design housing projects in any country we wished. I choose Colombia, and created a shelter system called ‘site and services’. My design envisioned very small plots, whose services would be enhanced by the local government, and the inhabitants would build their own homes in accordance with their capabilities.

In 1968 when I was on a Fulbright fellowship, I volunteered to design a shelter project for Sanatbhai Mehta, a social worker in Vadodara, but it could not be built. As good luck would have it, in 1972 Sanatbhai became Gujarat’s Minister of Housing, just when HUDCO was formed, and he invited seven architects to design low-cost housing. The other architects found this uninteresting, but my Jamnagar housing project became the first Economically Weaker Section Scheme funded by HUDCO. Seeing this project emerge, the World Bank approached me to work in Madras, and I drew on my thesis, creating an effective site and services program, resulting in thousands of plots becoming accessible to homeless people. From Madras, the World Bank carried this concept around the world.

Vasant Bawa, the founder of the Hyderabad Urban Development Authority, then engaged me to design low-cost housing for the Class IV Employees’ Federation of Andhra Pradesh, where I created small core houses on plots large enough for ‘growing houses’ to emerge. The owners added extra rooms, renting them out to kinsmen migrating into the city. This became a model for a self-managed urban rental system, reaching lower into the income strata to those who could not afford any monthly instalments; they became tenants!

The fees from this large project became the seed-fund for creating the Centre for Development Studies and Activities (CDSA) in Pune. CDSA prepared an innovative integrated rural development program in Ratnagiri for the governments of India and Maharashtra, supported by the United Nations.

Working with local people in Ratnagiri, micro-level, participatory, social input plans were drawn up. Through the Lead Bank Program, banks piggy-backed economic assistance on the social services schemes. This evolved into the Social Inputs for Area Development, a decadal program of the Ministry of Social Welfare, GOI, supported by UNICEF.

Out of this work in the late 1970s and early ‘80s emerged CDSA’s unique micro-watershed development approach, pioneered as a counterblast to the huge Green Revolution watersheds being promoted by the World Bank to increase cash crop production on flat, irrigated basins. Cash crops needed massive irrigation, hybrid seeds, fertilizers and pesticides. Ours was an environmental sustainability approach, employing re-afforestation, Nala bunding, contour bunding, percolation tanks, and small lift irrigation in micro-watersheds, enhanced by local NGOs called Pani Panchayats, who managed their own water accounting systems.

From the early 1970s, until now we have employed architecture as a social tool, building orphanages, and a network of social facilities for the Dalits of Maharashtra, centered at the Nagaloka campus in Nagpur. Empathy and compassion are catalysts of imagination and friendship. They are creators of self-knowledge and inner awareness.

Story Three

The Story of Imagination

Without our awareness, digital media, art critics, architectural historians and professors collectively promote a knowledge system inculcated within our meaning systems. These messengers are the high priests of our thoughts, and we believe what they say is good and correct, and like all gharanas, we promote this belief system, passing on ‘truths’ into the future.

Thinking within knowledge systems and designing our ‘creative works’ within their meanings are the unique feats of the human brain, driving our strongest emotional compulsions, through conformity, gifting us meaning.

If we are successful, our creations will be exhibited in the temples of our culture: within museums and exhibition halls. Yet, this meaning system leads one to something I call the human conclusion, wherein almost all architects and urban designers revert to a common formula in an interesting closure of their minds. To make this short, we all get trapped into the same belief system and the same predictable way of finding solutions within its knowledge system. Imagination is thrown to the winds and we are not conceptualising things that we cannot see or touch, but rather copying images from the media. We are seeking the approval of the ‘high priests’, most of whom have never designed anything! In other words: life is a trap.

As a child, I lived in a suburban house, next to similar houses, all laid out on well-drained, paved roads, each almost as ugly as the next, confirming the equality and homogeneous social status of the neighbourhood. What was called variety and freedom of choice came down to Ranch style, Spanish Colonial style or Classical styles; take your pick! This urban fabric was mind-numbing and mundane. Everyone shared the same bad taste! But our knowledge system spoke to us, telling us this was ‘good’. I saw analogies between our popular taste, common wisdom, and mass ignorance; all fed by stereotypes, forms of racial, gender, class and regional biases.

One Christmas morning I opened a magic gift that was the talisman of my future; a book, titled THE NATURAL HOUSE, by Frank Lloyd Wright, which changed my life forever. The book unravelled my thoughts and gave me a sense of vision for my future; a new knowledge system gave me a sense of meaning, as it told me of a path I could follow to self-discovery. It was not the images of dwellings integrated within the natural landscapes, but the credo, espousing nature, human scale, honesty of expression and functionality. This knowledge system fit well into my love for the great wilderness, rivers, lakes and the ocean. This sparked my thoughts, kindled my spirits and catalysed my imagination! For the first time, I could dream of alternative worlds, concepts and of objects that were not visible through my immediate senses.

One day I saw a large newspaper spread with photo-images of Le Corbusier’s forms and sculptural buildings in Chandigarh. It was love at first sight, carrying me on to romances with Ronchamp, La Tourette and the Marseille Block! But this was a ‘turning’, from one knowledge system to another, from a meaning system based in the organic language of nature to an abstract language of ideologies in the brain. Falling Water grew out of nature organically, while the Villa Savoy floated above, and away from nature, with all the trees around it cut down, creating an intellectual setting or abstract landscape within which this abstract object could sit! The American and European knowledge systems grew out of different contexts and meanings. Americans worship earth goddesses, and Europeans sky gods; Americans idealise log cabins in the forest and the Europeans idealise white marble temples on hillocks.

I resolved this conflict, dissecting the true meaning of architecture. First, I came to know that the truth of architecture is ‘place’. Each place has its unique cultural history and symbols. Each place has its own milieu and ambiance. Second, I realised that architecture is poetry; architecture speaks of intangible moments of ecstasy, resonating our deepest feelings.

My early works like the Alliance Française, CDSA, and the Mahindra United World College of India were all catalysed by Wright’s credo of human scale, kinetic choreographies of moving through space, and integration with context. My later works drew inspiration from what I now call the ‘culture of construction’.

In Bhutan, I wanted to use the culture of local materials, local craftspeople and their simple construction management, guided by monks. In Pune, creating a large industrial pavilion, I drew on the culture of our steel and machine manufacturing technologies. I think it is important that we realise that we all think, imagine and create within knowledge systems and that different knowledge systems are competing with one another. There is cultural imperialism trying to invade our minds and place alien meanings within us. As the suburbs of my youth, we are victims of popular taste and common wisdom.

Star-chitects are creating monumental stunts and making dramatic follies, all yelling, “Look at Me!” By applauding these inane fabrications, we are succumbing to insipid cultural colonialism. I find it perverse that no major architectural critic is speaking out against monstrosities like the CCTV Tower in Beijing, ugly urban spaces such as La Defence in Paris, or the terrible museums emerging year after year across the globe. In India, our own IT giants have spread ugliness in Bengaluru, Hyderabad, Pune and Gurgaon, missing an opportunity to gift us a new spirit of built form. Even the ‘high priests’ seem to have their mouths sealed in front of their own knowledge system!

Architecture and urban design are potential catalysts of imagination and intellectual friendships. They can be creators of self-knowledge and inner awareness.

Story Four

The Story of Inclusiveness

City plans are not artefacts of accident, but rather arrangements of contrivance, with urban slums being direct results of elite urban policies, foreign planning models, automobile and real-estate-driven concepts, and an amazing lack of public imagination. We design cities as if they are tinker toys, not as all-inclusive socio-economic systems!

Yet, our cities are the unique feats of the human brain, driving our strongest emotional compulsions. City planning around the world leads us to something I call the human conclusion, wherein almost all urban societies come back to a common set of urban crises, in an interesting closure of the human condition. All city plans, directly or indirectly, ironically exclude most urban citizens.

To summarise, can I say we all are trapped into the same urban conundrum, and the same predictable inhumane city, be it Mumbai or Manhattan!

In other words: life is a trap. Or, is it? Modern city planning theory and practice can trace its origins back through history, even to Greek cities and Roman garrison towns, and to royal oriental capitals. Modern city plans, campus plans, information technology parks are just slight variations of British Cantonment plans, where the military area created a unique social space, defined by one’s race, occupation, gender and rank! The Indian jawans, at the bottom of this socio-economic pyramid, were, in fact, part of an elite minority admitted into this unique urban estate, characterised by potable water, sewerage systems, storm drains, paved roads and social services. The real cities of India were left to rot!

This model is one of the precursors to ‘globalisation’ in urban planning where gated communities and malls have replaced the lively, informal public domains of traditional settlements. The loss of social space is a metaphor of the loss of community and indigenous identity.

An undeclared strategy of city planners is to replace ‘vernacular culture’ with institutional culture, right from the plan of the city to the architecture of the buildings. Uniforms have replaced platforms, which once gifted personal cultural richness and identity. In 1979 I embarked upon an adventure into the Kingdom of Bhutan, crossing the no-man’s-land from Bagdogra to Phuentsholing, where foreigners were forbidden! Not more than five other Caucasians were in Bhutan when I arrived, and I had a mission to prepare micro-level plans to enhance the quality of life for isolated villagers. His Majesty concluded that no one could participate in Bhutan’s development without personal knowledge of the kingdom, ordering me to head across Bhutan by jeep, over roads cut from cliff faces, running deep into the isolated mountain wilderness.

Upon my return to Thimphu, I quickly befriended the small group of young officials, and we set upon a strategy involving the deputation of students to Pune, and my setting-up a small planning office in Thimphu.

We were fighting the global strategy to introduce cash crops into the valleys, creating nutritional problems as mono-cropping replaced self-sufficient food cropping. Bengali truck drivers introduced STDs along roadside hamlets, and cash crops like cabbage dominated daily diets, stimulating iron imbalances and related diseases.

During this stay in Bhutan I noted the healthy social life wherein department directors, ministry secretaries and seniors in the military all played archery each afternoon with their drivers, office attendants and maintenance staff. They all laughed and danced and drank chhaang! Everyone was a part of one social group, and there were no divisions. They were bonded together out of compassion for their community.

Over the years I watched Thimphu grow from 5,000 to 8,000 and then to 37,000 people when in 2001 I won a competition to prepare the capital plan of Bhutan. The Bhutanese Prime Minister, Jigme Thinley, who was initiating the concept of Gross National Happiness, took a special interest in this activity.

We struggled together with a small team of young Bhutanese architects to discover pathways to make our capital plan more inclusive, resulting in the Principles of Intelligent Urbanism. These principles acted as a charter through which to filter decisions in all our discussions, regardless of whether in a village meeting or a cabinet meeting. We immediately set out to involve villagers in planning their own watersheds, transforming them into what they called Urban Villages, through land pooling.

This charter of working guidelines grew out of our concepts of gross national happiness, and from my earlier work preparing plans for provincial capitals in Sri Lanka; housing communities in India; development plans for cities like Thane and Kalyan; and for other human settlements in South Asia.

Lyonpo Jigme Thinley used the fate of Bhutanese archery matches as a backdrop to our planning work. He rekindled memories of my first visit, when the working day was from eight in the morning until two in the afternoon, and the free time was used to meditate, and to play archery with traditional bows and arrows, bonding people into close-knit communities.

One day a foreign consultant arrived carrying a ‘power bow’, made of fibreglass, with slick arrows, shooting twice as far as any traditional bow!

That day changed Bhutan forever, dividing every archery range into two parts: one part for the power bows and the other for traditional bows and arrows; one for the rich and one for the poor!

A class-based society was born on Thimphu’s archery grounds! Soon all senior officials were returning from foreign tours with power bows, costing the annual salary of their drivers and office attendants.

Thus, the archery matches evaporated as a binding social force, globalising the entire city into a divisive, competitive society.

This parable taught me that defining factors in traditional societies emerged from within diverse societal components, expressing themselves to society as an inclusive collage of plural forms, from the inside outwards. On the contrary, in our contemporary institutionalised global cultures, the uniforms are imposed from the outside inwards, suppressing down from the top, on down into the parts. Our vernacular dress and built forms are ‘expressions’, while our institutional uniforms are ‘suppressions’! This system of articulated stratification lives with us as urban planners, tempering the way we think, how we deal with ‘others’, and even our self-images.

Inclusiveness is essential for the evolution of civilisation, yet we seem to be moving backwards!

Inclusiveness is the catalyst of urban planning imagination, and the creator of civility. It gifts communities self-knowledge and raises inner awareness of ‘the right to the city’!

Story Five

The Story of Reflection

Collecting memories, attaching subjective meanings to these recollections, and arranging these past events that have faded from reality into virtual concepts, are unique feats of the human brain, driving our strongest emotional compulsions. Yet, this subconscious archival project leads us to something I call the human conclusion, wherein almost all human societies place values on their memories grouping them into a common narrative of popular wisdom in an interesting closure of the human condition. To make this short, can I say we all get trapped into the same story of life, and the same predictable outcomes devoid of imagination?

In other words: life is a trap. Or, is it? Architects, urban designers and artists are writing stories of the future, drawing on memory and reflections of the past while creating new narratives.

Our compulsion to deal continuously in future scenarios leads to a kind of schizophrenia where we are creating choreographies of future scenes, with people moving in our imagined spaces, yet drawing on past references as building blocks for our ideas.

Unfortunately, most of the design production we see today is plagiarised from the web, or even cut and pasted in the spirit of commercial proficiency!

Urban public policy experts, urban planners, and architects, per force, end up writing reports, and as life proceeds, we learn that fiction goes down better than prose with our clients, and a new kind of creative license emerges. Good professionals write well, and successful ones learn the art of weaving conceptual fictions into the prose of clients’ budgets and functional needs.

Sooner or later, some of us leap out of our professional writing into expressing our reflections and observations in artful forms of literary attempts, like my book LETTERS TO A YOUNG ARCHITECT that has now been published in four languages. Frankly, that was a counterintuitive outcome, as I never imagined that my writing would figure on the Top Ten Best Selling Non-fiction Books in India, and be read by people of all ages and dispositions.

The lesson is that more of us must write and we must teach our students to write! One of my successes at CEPT University was to influence the curriculum, requiring all incoming students to take a writing laboratory course, beginning in the first semester. My own education required me to take writing classes, and that led me into publishing in EKISTICS and Habitat International, and authoring chapters in books published by the RIBA, Rutledge and numerous Indian publishers. I say this only to encourage educators to do the same across the country and to make our young professionals truly literate citizens who can express important opinions and thoughtful views on our society. Writing and editing is a part of my daily life, and I remain an unwilling member of the Editorial Board of CITIES Journal in UK, and others.

My career as an institution builder and public policy analyst led me into major writing projects. In 1983 I was asked by the United Nations to write their Theme Paper for the upcoming Seventh Session of the United Nations Commission on Human Settlements.

This was an arduous task defining the goals and strategies for urban management that 58 member nations would mutually ratify. In addition to writing, it was incumbent upon me to present the draft to each of the United Nations Regional Commissions so they could assess the possibility of my offending a member state’s sense of propriety. This task stretched over months in Nairobi at the UNCHS (Habitat) Headquarters.

About a year later the Ministry of Urban Development, GOI, requested me to represent India at a Non-aligned Conference on Urban Development in Sweden, where I was asked to make a major presentation to the 300 or so international delegates.

At the end of my presentation, a senior Finnish official arose grabbing much attention with a strongly worded question to me, which took the form of a major accusation! Before coming to the point, she laced her attack with several insinuations, and then said, “The paper you have just presented is an insult to this gathering! Most of us sitting here were signatories to the Charter of the Seventh Human Settlements Commission Meeting held in Angola. The paper you have just presented diametrically opposes the values and principles that we have debated and agreed upon! What do you have to say for yourself?” There was a hushed silence in the large auditorium, with deadly glares directed my way from fellow speakers on the podium! I got up, walked slowly to the rostrum, and said, “Madam, thank you for your wisdom! I am the author of the paper you have signed! Do you have any more questions?” The large audience broke out into howls of laughter and applauded my rebuttal enthusiastically.

So, writing can have euphoric moments as well as depressing ones. In 1986, I wrote the Asian Development Bank’s White Paper on Urban Development, arguing to the Board that the ADB should open their lending to urban infrastructure investments, alleviating health and nutrition stresses in Asia’s cities.

After presenting to the Board, and receiving cautioned acceptance, I suggested they assemble a conference of experts, documenting their support, and allaying their doubts.

Until that piece of writing, the ADB restricted its lending to rural and agricultural development, based on the popular wisdom that urban investments catalyse urban migration. It was a moment of euphoria for me when I learned that the Board of the ADB passed a resolution, entering the urban sector of development.

So, life is not a trap after all! For the true artist, there are secret moments of transcendence, and moments of inspiration when the profound arches unhampered over day-to-day trivia. Within that momentary sliver of self-realisation lies one’s eternal truth and being.

Writing, urban planning and architecture are creative catalysts of imagination. They are creators of self-knowledge and inner awareness.

Epilogue: Jhabvala Lecture

Born in America, my karmabhoomi is here in India. I was drawn here to the subcontinent through subconscious dreams and primordial urges embedded in my soul. Yes, narratives hidden within my primordial being were calling out to me to come and live in India. Once I set foot on Indian soil, I knew I’d found my home.

I have been blessed to know India through its many ‘living layers’, of times that float one above the other, sharing geographical space and time simultaneously in the form of real people and friendships.

Through my princely friends in Gujarat in the 1960s and Bhutan I lived the stories of medieval lives, and I designed places appropriate to their heritage; through my friends in the bureaucracy I lived the lives of the socialist state, and I designed towns, re-planned cities and created large housing estates in the spirit of a ‘supply-side economy’; through my friends who were early entrepreneurs I came to know the meaning of the mixed economy, and its precarious life, and I helped them find identity through their buildings. Now we live in a capitalist global economy, and my clients’ markets spread around the world, and I must work in a culture of construction that is both very Indian, and at the same time global.

Each of these layers has had its own work ethic, it’s own thinking, and its own kinds of human relationships. So, the lesson of India lies in its people and through their relationships! It lies in their stories knitted together into great epics, generating shared happiness and sense of fulfilment. Yes, I found true happiness in India, Bhutan, Sri Lanka, Nepal and Bangladesh. I learned that life is not about the projects we have in hand or our wealth, but life is simply the quality of our friendships that grow into our being along our journey.

If life is a trap, adventure, compassion, imagination, inclusiveness and reflection are our creative escapes! ♦

Image Credits: CCBA Designs Pvt. Ltd.

PROF CHRISTOPHER BENNINGER has studied urban planning at MIT, architecture at the University of Florida and at Harvard, where he later taught. He has worked under the Spanish architect Jose Lluis Sert and has studied planning under Kevin Lynch, Herbert Gans, John F C Turner and Constantinos Doxiadis. Professor Benninger has been a consultant to many well-known organisations including the UNCHS [Habitat] where he wrote the Theme Paper on education for the Seventh United Nations Commission Meeting on Human Settlements. He is also an avid writer, who authored the books titled ‘Letters to a Young Architect’ and ‘Architecture for Modern India’. He is a distinguished professor at CEPT University, the President of the CDSA Trust, and has served on the boards of the School of Planning and Architecture, New Delhi and the Fulbright Foundation in India.