The National War Memorial in Delhi by Chennai-based Webe Design Lab is a built landscape that emerges from an unprecedented participatory process, programme, ambition, and typology. In its comprehension, the project creates a space of sanctitude in memory of Jawans, and of pride, and honour for their families and citizens of India, which is respectful to the context.

BACKGROUND & TIMEFRAMES

One of the most enduring images from Delhi since 1931 is the axis of India Gate, forming one of the pinnacles of the ceremonial Vijaypath (the erstwhile Rajpath or the Kings Way) – the currently debated Central Vista. The ceremonial boulevard was designated by Edwin Lutyens as the centre of what he contrived as a ‘modern imperial city’, tethering an enclave of buildings of political eminences such as Rashtrapati Bhavan (formerly the Viceroy’s Residence), Secretariat Building, Vijay Chowk, designed by Lutyens himself and Herbert Baker. Renowned as one of the foremost European designers of war memorials and graves, Edwin Lutyens designed the All India War Memorial, popular as India Gate in tribute to the soldiers martyred in the First World War from 1921-31. Beyond it, since 1972 stands the Amar Jawan Jyoti, an inverted bayonet with a soldier’s helmet – an insignia in homage to India’s victory in the 1971 war with Pakistan and to the brave soldiers who died while serving India’s armed forces. The area surrounding this is marked as the Lutyen’s Bungalow Zone (LBZ) which is also enlisted on 2002 World Monuments Watch list of 100 Most Endangered Sites. Needless to iterate, it is a site of cynosure – an avenue in focus with the ongoing debates around the Central Vista project. It is a landscape of immense cultural, historical and political significance.

The National War Memorial comes at the hem of almost 60 years of contemplation and consideration. Ongoing since 1961, the discussion put forth by the Armed Forces over the years finally saw fruition in 2014, gaining momentum presided by the current Government. In 2006, a conceptual scheme had also presented to the President of India by Charles Correa.

In July 2014, a competition was announced by the Government of India on its online portal for the National War Memorial and Museum. “It is India’s first commemorative memorial for the wars and military conflicts since 1947. Post India’s independence on 15th August 1947, our country has been involved in many conflicts of different magnitudes and participated in innumerable operations both inland and overseas. Our country continues to engage in counter-terrorism operations and proxy war from across the front resulting in number of battle casualties. While a number of area/battle specific memorials are built across the country, but no memorial existed that was all encompassing.,” read the premise in the Brief. It ‘proposed that lawns within the Hexagon, without disturbing Lawns V, VI, Chhatri(Canopy) and Childrens’ Park be utilised as the site’. With unambiguous guidelines, it called for a design that would ‘stand tall between the expanse of manicured lawns and grand buildings […]’must be majestic and timeless.’ At the same time, it emphasised that ‘the design should pay more attention to landscape-based interventions rather than any major construction except for commemorative wall, platforms and minimal public utilities etc.’ and ‘should be in harmony with the existing landscape of the Hexagon.’

The competition was conducted in two stages; it garnered around 427 submissions in an overwhelming response. A multidisciplinary jury comprising of architects, designers, academicians, singers, bureaucrats, social workers, was instituted which selected 9 entries for further discussions. After a closed presentation reviewed by the committee, Chennai-based WeBE Design Lab were announced as winners and coveting the third place for the National War Memorial. The winning entry led by Yogesh Chandrahasan of WeBe Design Lab, was commissioned for construction. Mumbai-based Sameep Padora & Associates (sP+a) was announced as the winner for the National War Museum.

The execution of both the National War Memorial and Museum were assigned guidance by a Special Projects Division overseen by the Chief Administrative Officer (Ministry of Defence), and the Military Engineer Services. The National War Museum dealt with unbidden controversies before it was shelved. A welcome contrast, the National War Memorial was inaugurated and dedicated to the Armed Forces of India on 25th February 2019 by the Prime Minister of India.

DESIGN

The design of this Memorial emerges from a context of legacy – the legacy of 25,000 Jawans (soldiers) who lost their lives in various wars and operations such as ‘the Indo-Pak wars of 1947, 1965, and 1971; the Indo-China war of 1962; the Kargil war of 1999, besides the peace keeping operations in Sri Lanka, counter insurgency operations, and internal conflicts within the country’. It emerges from the remarkably, surprising mature process of a Government-organised competition. It emerges from this historically and politically charged site in the C-Hexagon, India Gate Complex.

Entitled ‘P u n a r j a n m [ पुनर्जन्म ]’ (rebirth), this is a non-building that articulates the legacy and the context, neither partial to one or the other, but bridging both. A quote of Captain Vikram Batra, laid the conceptual foundation of rebirth for the design.

“Either I will come back after hoisting the Tricolour,

or I will come back wrapped in it,

but I will be back for sure.”

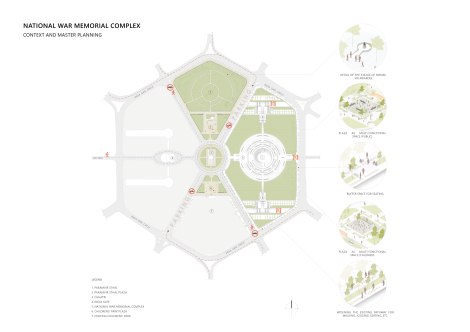

Within 42 acres extended in the C-Hexagon, the design subscribes consciously to the formal rhythm and geometry of Lutyen’s zone and transcends into a plane of layers that traces the lie of the land.

The architects refer to it as a ‘semi-subterranean design’ which respected the governing heritage zone that it was a part of. The planning was delineated across three parts:

- The Param Yodha Sthal: A dedicated walkway connecting statues of the 21 Paramveer Chakra awardees.

- The Rashtriya Samar Smarak (National War Memorial) : consisting of the central zone (Circles of Emotions) and utility complex on both north and southern side.

- Public plazas

Past the crowds that converge and the languorous circumventing of hawkers that one attempts at the India Gate security barricades, the linearity starts to thin as one enters the complex – the Circles of Emotions.

The elements of design – these four circles – namely, the Circle of Immortality (Amar Chakra), Circle of Bravery (Veer Chakra), Circle of Sacrifice (Tyag Chakra), Circle of Protection and the Path of War are profoundly a personal take of the design team, on conveyance of ‘emotion and design: establishing symbol and memory’.

On arrival, one begins their journey at the Circle of Protection. Enveloped by 690 trees, the memorial area is relatively calmer, and protected from the outside. “It personifies the territorial line of control,” write the architects, “The soldiers who are still there trying to safeguard us in places unseen. The ordered arrangement of the trees reflect the disciplined life led by them.”

Subsequently, one finds themselves ushered into a promenade, a wider avenue. It is here that one begins to understand the intrinsic nature of the design, the idea of the pastoral and the ordered landscape. In plan, concentric layers radiate from the core, each manicured and meticulous, inspiring a movement which is curated. The walk is long-drawn but implicit suggestions of the design start expressing themselves along the trajectory. It is a negated ziggurat that moves downward closer to the earth – a deference, restrained posture.

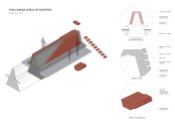

The readability of the circles becomes more pronounced at the Circle of Sacrifice (Tyag Chakra). While making a reference to Chakravyuha, a traditional concentric military formation, the sculpturesque layout inscribes names of 25942 martyrs over 8 segments of 2 walls each. In its simplicity of a precast RCC structure holding up simple self-interlocking granites chiselled with names of the Martyrs with their names, rank and numbers, it offers an experiential way of remembrance. Rows and rows systemised chronologically outline an enormity of the loss, a physical echo of the absence, a memorial for an individual soldier, not a general monument.

The visibility of the layout strengthens as one moves onwards to the Circle of Bravery. At the threshold, one pauses looking down as the Eternal Flame comes into view, and reconciling with the breadth of the memorial that reveals itself. The Circle of Bravery is a semi-open corridor that circumvallates the main plaza. Six bronze murals inspired from the painting of Lt Col A J Arul Raj (Retd), made by renowned sculptor Ram Sutar narrate details from six post-independence battles fought by the defence forces. Considering this is a singular representation, the exhibits leave a lot to be desired. In absence of a Museum, perhaps, these can be substantially curated . Additionally, the architects mention that this circle ‘holds a large semicircular rainwater harvesting tank. The water from the paved areas and landscaped areas in the central zone are collected and reused for irrigation.’

The obelisk carrying the eternal flame finds an eloquent place in the Circle of Immortality (Amar Chakra), the innermost core, the sanctum of the design seen against the tessellations of the stairs. Prosaically, it is the radiating centre defined as a ceremonial space; poetically, it is choreographed with an edificial symbol rising from the earth, meeting the sky, immortalising the memory of the soldiers. “The central obelisk and the opening out of the memorial intends to hold a subtle hierarchy to the India Gate and the Chattri,” say the architects. It is apparent that from here, the comprehensive plan sustains the symmetrical, hierarchical layout of the context.

The circles represent a nexus to the intersection formed by the Rajpath with the Yudhpath (life of a soldier). On either sides, the landscape extends and the edges expand into these subterranean pathways – Path of War. Of this, the architects write, that they ‘were designed as preparation space which displays a brief history of Indian Defence force. The upward ramp from the gallery does not reveal what stays ahead. All that one could see the pinnacle of the obelisk – the destination. On climbing up there is a sudden opening up of the entire spread of the memorial which is a parallel drawn to the war moment.’ These pathways were connecting the site of the War Museum and the lawns. The connections drawn at the central core also illustrated ‘a symbolic intersection of the Rajpath and the Yudhpath- “Path of life” and “Path of war”.’

It is a well-meaning attempt, translating the ‘emotions which a soldier transits through when he/she goes to war’ into a geometric manifestation. Beyond the creation of what the brief called for, by organising separate sections, the design places an emphasis on people to consider each space with its own distinct history.

The material palette used is another conscious nod to the context, and because of that, the space innately responds to the heritage zone, not very inextricably different from the existing landscape. Elaborating on another relevant integration, the architects say that ‘the lighting in each circle enhances its emotional component differently. The lighting in the central court around the eternal flame spearheads sideways and up building a sense of eternity as it fades out. The Tyag Chakra seems floating with a series of small lights which resembles the oil lamps that are light in memory of the beloved ones in any Indian home. The streaks of light on the steps create a sense of transition through the concentric rings. As much as the light brought in emphasis and character, the darkness made the required experience deeper and absorbing.”

At the approximate cost of INR 176 crores, the Memorial was designed and built in a time span of 20 months. Given the stature of the project, it has faced its own fair share of disputations. The proposed site had encroachments and there was concerns raised by the Army about vacating World War II barracks on the adjacent sites. But unlike its counterpart – the National War Museum, this project proceeded in principle.

SIGNIFICANCE

As a project, the Memorial negotiates a wide variety of expectations. How does one build in this incredible monumental core? What does a competition like this mean for a practice in India? What does it mean for the young practice which was appointed with this honour and responsibility? How does one design a memorial that is able to convey such a complex and significant military history? How does one define an identity for such a place/space in public imagination? In fragments of this process, the project’s position gets consolidated, and merely viewing it as an architectural object flatlines it.

For a practice that was established in February 2010, by eight friends/studio partners from School of Architecture and Planning, Chennai, and who won two commendations (first place and third place) in this competition, it compellingly gives credence to an optimistic view of what it means for a young practice to be involved with a project of this scale and import. As Yogesh remarks in his interview, “We were not in a great circumstance at the time of the competition. Especially after Chennai Floods the construction field was completely down. It was the time we were looking for other possibilities and practices to build our portfolio.” In a separate interview with Indian Express, that they were fortunate enough to receive emotional, resourceful and financial support from friends and family.

Whatever the reading of the architecture and its visual matrix, the reality of this Memorial is in the course of its trajectory which provokes reams of conceptual comment and every chance of it becoming a widely debated work. It is noteworthy that despite being a Government-led initiative, the range of the competition was equally expansive. It diverged from the familiar ‘invited’ and ‘closed’ competition template.

To some, in the detailing and finishing of construction, the gaps may seem quite tangible. However, the architecture does not claim overt attention. Nor is it a sudden, jarring change for the landscape, neither does it attempt to emancipate the present context from any history. Even as an insert of over 109265 sqm, it still remains as a background and in deference to the India Gate monument. At this scale, even though the project embraces the vast peripheries of its given site, it is commendable that the invisible becomes visible only by navigating the journey and the power of conveyance that the architecture mediates for the visitor.

Within a landscape that has not witnessed a similar intervention in recent times, and whose appearance could not therefore be anticipated, on many levels, the design also breaks down preconceptions of what a late 21st century building should be. It remains devoid of any trademark approach, of any ‘iconic’ signifiers. Although it absorbs features from accepted historicity such as the Mughal Gardens or the Chakravyuh, but there seem to be none of over-the-top ‘inspired’ motifs or ethics that characterise it. That is a refreshing virtue. Additionally, in its reticence, it sets a precedent of how to deal with a site like this.

As a project, it acknowledges that important beginning of a transition from existing opaque processes of state-sponsored projects. Yogesh admits that except for a rare exclusion, the project itself has not changed from its inception but evolved with discussions with those directly involved. As a rhetoric, it is an assumption that it may not have been easy to follow the Government and Ministry of Defenses’ drift for the finer nuances of the argument but that does not seem to the case here.

In the larger discourse, it edifies a conduct for a competition that was initiated by the Government, and the successful implementation of a programme, especially one where a young firm with limited influence could propose a purposeful, zealous plan which was veritably realised. Relatively, this is in sharp contrast to its correlative programme, awarded fairly to Sameep Padora & Associates, which was dragged into an irredeemable controversy owing to professional insecurities.

At a time when the architectural fraternity in India is debating the vicissitudes of projects of national significance in the same vicinity, one realises that a competition of this kind is too infrequent to claim a space of change. While it is important to see the architecture of this Memorial as a sensitive design, and a product of history, it is also crucial that it is seen as a demonstration of a successful a state-sponsored design competition that empowers any firm through an accessible system of participation.

DISCUSSION

In conversation with MATTER, Yogesh Chandrahasan of WeBe Design Lab discusses the development and curation of the design, the implications of the National War Memorial and the rewarding response to the project.

An insight into the making.

Q: The Global National War Memorial & Museum Competition for India

completely reimagined the way architects could engage with a public project. Could you give us a background on the competition process for you? Please tell us about your experience. Did the composition of the Jury Panel make it different than any other architectural competition?

Yogesh Chandrahasan [YC]: We rarely see such initiatives taken for designing the public spaces in our country. It is one of the successful design competitions conducted that was also executed. We were lucky to see what we envisioned to also be executed. The competition was floated in the Government portal: mygov.in. We were surprised to see that the portal had many open competitions not only for special projects but also varied scales and expert areas giving opportunity for all age groups and fields of work. The Ministry of Defence hosted this as an international two-stage competition. Stage 1, being the concept scheme submitted online and Stage 2, as the detailed design presentation to the Jury panel.

We were not in a great circumstance at the time of the competition. Especially after Chennai Floods, the construction field was completely down. It is the time we were looking for other possibilities and practices to build our portfolio. Working for this competition was one of the best experiences that took us back to our school days.

It was definitely an unusual jury panel consisting of about 20 renowned experts and bureaucrats from diverse fields.

Panel:

Architects: Ar Christopher Benninger, Ar Jaisim Krishna Rao, Ar PSN Rao, Ar C N Raghvendran

Academicians: Prof Chetan Vaidya, Prof Mandeep Singh, Dr K S Anantha Krishna

Actor /Director: Mr Amol Palekar

Artist: Mr Jatin Das

Singer: Ms Hema Sardesai

Social Worker: Ms Sudha Murthy

Ministry of Defence: Mr JRK Rao, Ar Mala Mohan, Lt Gen Anil Chauhan, Lt Gen Rakesh Sharma, Lt Gen Satish Dua, Air Marshal Ajit S Bhonsle

Committee: Ar Divya Kush (IIA), Ar Ashutosh Kumar Agarwal (IIA)

Q: How did the design develop internally within the team – how was the studio organised in the process? How did the design evolve through the competition stages? What were some of the defining moments in the design for you? It is a project arranged in many thematic layers – it is an urban project, it is a project of nation building, it symbolises pride, memory, patriotism, legacy et al. What has been the main approach conceptually to resolve this in the design? What were your main observations?

YC: As a firm we believe in co-working and co-creation. We are a partnership concern. The set-up is interesting and enriching bringing in varied perspectives through the process. We had open feedback sessions on the design with all partners and their teams in our office during the competition process. It was made sure that the sessions were critical and every feedback was taken in a positive way. The design is an outcome of the entire team.

Two entries from our office got shortlisted for Stage 2. The entire office was divided into two of which one half was helping our team and the other was working with another partner, Ar Karthikeyan. Some of our old interns too joined us to help then. The responsibilities were split and given to individuals to manage and execute it.

As part of WeBe’s Process we believe every space should bring in a sense of connection between people, their culture, and the surrounding to build a collective sense of belonging. This in itself had varied aspects that drove the design.

While developing we were also very conscious that the design should:

1) Reflect the brief given in the competition.

2) Be simple and provoke emotion.

3) Have very less built (covered) space.

4) Respect and merge the existing landscape and setup.

5) Create a common connecting point for anyone who walks in to experience it.

Q: Were there any memorials/ influences/ mentors that served as an inspiration or recall for you?

YC: We did study about memorials across the world but that was not an influence. As a firm we believe that every project starts a clean state. We were looking through history, context and the project backdrop for a strong initiation point.

“Either I will come back after hoisting the Tricolour,

or I will come back wrapped in it,

but I will be back for sure.”

This quote of Captain Vikram Batra made us place the design around the concept of ‘Rebirth’.

There were many metaphorical interpretations:

The Rajpath (Path of Life) cuts across the Yudh Path (Life of a soldier). Similarly, each circle has a story and emotion built around it. For example, the Tyag Chakra (Circle of Sacrifice) is inspired from the ancient war formation “Chakrvyuh”. The soldiers form a concentric arrangement to protect their king. Every circle is an interpretation of different acts of a soldier which is translated as different emotions for people to experience.

Q: Located in one of the most significant, and historic avenues of the country, and visited by people irrespective of class, creed, race and religion, context and community must have been one of the core concerns to address. Could you elaborate on the focus of these aspects specifically?

YC: To work on a site like this is a big dream for many. Being rich in history, architecture, culture, people’s footfall, these were all thought through. The design brief was very clear that the Memorial will be designed as a public space. Irrespective of the typology, the space had to be designed and experienced by everyone.

For people from varied cultures and ethnicity a common connection had to be established. As mentioned earlier, the life of a soldier was that common point. We went into looking at it deeper to build the experience around it.

Q: Did the design evolve/change post the competition? Were there any limitations or areas that you were unable to realize or that transformed over the course?

YC: As I said earlier we strongly believe in co-creation. Apart from WeBe we had 8 expert teams working with us on making the project what it is now. Lighting, planting, artworks, information design, structure and services are some of them. Everyone contributed to enrich the design.

Yes. It was not easy to have a dialogue and convince the officials in some circumstances. One of the key components of the memorial, “resurrecting soldiers” reflecting the idea of “rebirth” was removed during the course of translation.

Q: The Memorial itself extends into a permanent exhibition space. Was the exhibition curated by your practice? If so, what were the ideas behind its curation?

YC: More than an exhibition it is a space to experience. In which the Circle of the Bravery ( Virta Chakra) is a gallery holding some significant stories of Indian armed forces for people to think, to know our defence history and more.

The required content was given by the officials and we curated the space along with the help of artist Lt Col.Arul Raj, Sculptor Mr Ram Sutar and Mr Anil Ram Sutar.

Q: Considering the spectrum and typologies of work you were dealing with prior to the competition, what have been some of the challenges and opportunities for you to embark on a project of this scale, in public eye and dealing with a large government project? For the project, and also for the studio.

YC: When we look at spaces through the lens of people, culture and surrounding to build an experience, typology does not matter. However, our portfolio had smaller projects then, partners are specialised to work across varied scales – both, big and small. There are two simple but important aspects around which any project is developed – Every project is unique and begins with a clean slate and Every project needs a unique team. This works across typology and scale.

Definitely the Memorial is a project of different nature and was a new experience. For a firm like ours, the major challenge in working for the Government was on funding, their preset procedures and protocols.

Q: Has the project influenced the way you think about the building, architecture and your practice?

YC: As much as we plan, spaces unfold and are not always the way we think. Subtle but crucial, the spaces should give the scope for adaptations and interpretations. Allowing it to take form naturally. Beauty lies in natural adaptation.

Q: The project was completed in 2016. It is one of the most visited public spaces in our country. What sort of a response and reaction has it received?

YC: So far, the response is positive most times and surprising sometimes. We envision something. Reality always holds something in store. Not everything turns up the way we want. This place ended up being much more than what we had thought it would be. From the silence it brings in everyone, to the patriotic shout outs during wreath laying ceremonies, this space has brought us many surprises. The thanks and blessings showered by the soldiers themselves! By nature, this place carries so much more than anyone can plan for. No doubt that it remained a void in so many’s life. I read the Google Reviews for the project once in a while to understand the thoughts. It is very fascinating to see the translation the space has taken and the emotion everyone undergoes inside the memorial. It is truly overwhelming.

Information

Global Design Competition for National War Memorial and Museum. New Delhi: Ministry of Defence, Government of India , 2016

Plot Area: 42 Acres

Year of Completion: February 2019

Location: C- Hexagon, Lawn 1,2 ,3 4, Central Delhi, India

Client: Executive Agency of National War Memorial and Museum,

Ministry of Defence, Government of India

Architect: Yogesh Chandrahasan, WeBe Design Lab, Chennai

Project Team: (WeBe)

Satish Vasanth Kumar

Udhayarajan

Malli Saravanan

Visuwanathan,

ViJay Prakash

Ranganathan Ravi

Balachandar Baskaran

Abhishek Tiwari

Anjana Sudhakar

Consultants

Project Management: Turner Project Management India Pvt Ltd

Planting Design: Mrs Savita Punde, Design Cell, Gurgaon

Structural: Roark Consulting Engineers LLP, Delhi

MEP Consultants: Edifice – Delhi & ATE – Chennai

Lighting: AWA Lighting Designers

Fountain: Ripples & Mr Premkumar

Signages: Ishan Khosla Design

Artist: Lt Col A J Arul Raj (Retd)

Bronze Sculpture/Murals: Ram Vanji Sutar

Visual Documentation: Maniyarasan

Credits

Photographs: WeBe Design Lab, Maniyarasan, Madhumitha, Government of India

Drawings: WeBe Design Lab

Text: Maanasi Hattangadi

Site-Visits are project reviews on Matter visited by the designer / critic and scripted after a dialogue with the author/architect. Write to us on think@matter.co.in if you wish to review a project you know OR if you wish your project to be reviewed on Matter.