An editorial project by Matter in partnership with Şişecam Flat Glass, PRAXIS investigates the work and positions of diverse contemporary architecture practices in India. Rohan Chavan of Mumbai-based RC Architects elaborates on the events, influences and inspirations he carries within him as he designs evocative spaces in the public and private realm. The interview explores the intents and concerns that Rohan deals with through his engagement with professional practice and academics.

RC ARCHITECTS

Rohan Chavan

Tell us about the inception of your practice, the formative years, and the ambitions it was informed by.

RC: We started in April 2015; I worked for seven years before that with Correa, Benninger and Mehrotra. I was quite fortunate to have teachers like them, from whom I learnt architecture through their experiences and explorations. As Christopher has rightly said in Letter to Young Architects, “there is only one kind of good luck, and that is to have great teachers” – I totally agree with him and I have experienced that.

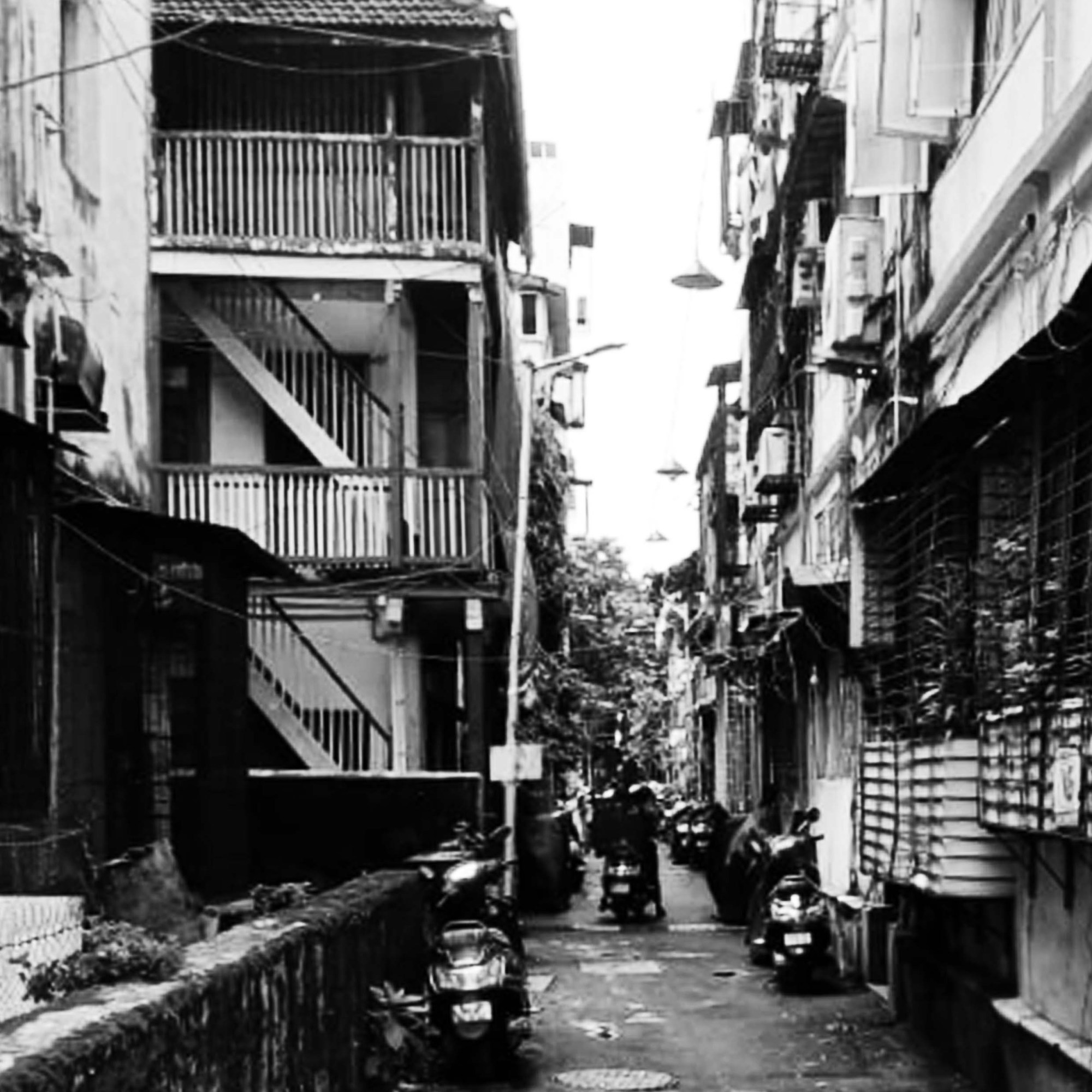

Our first setup was in a small house at Charni road, a typical wadi house (similar to a Khotachiwadi kind of architecture) that had a straight flight wooden staircase that would lead to the first floor. The house had three rooms arranged like a railway compartment. The first room was the studio, the second a sleeping and a TV room and the last room was the kitchen, toilet and storage.

The first few years I worked by myself with no staff; my family friend’s son and daughters who were studying architecture at that time would take part in my projects to help along. It was an exciting phase where everything was raw and fragile; neither were we burdened by any particular architectural style of work as I was more interested in my own freedom and response to the design problem to explore space, materials and climate. The first couple of years we did some interesting work that triggered our imagination on many fundamental aspects of space. From the Charni road studio we did projects like,

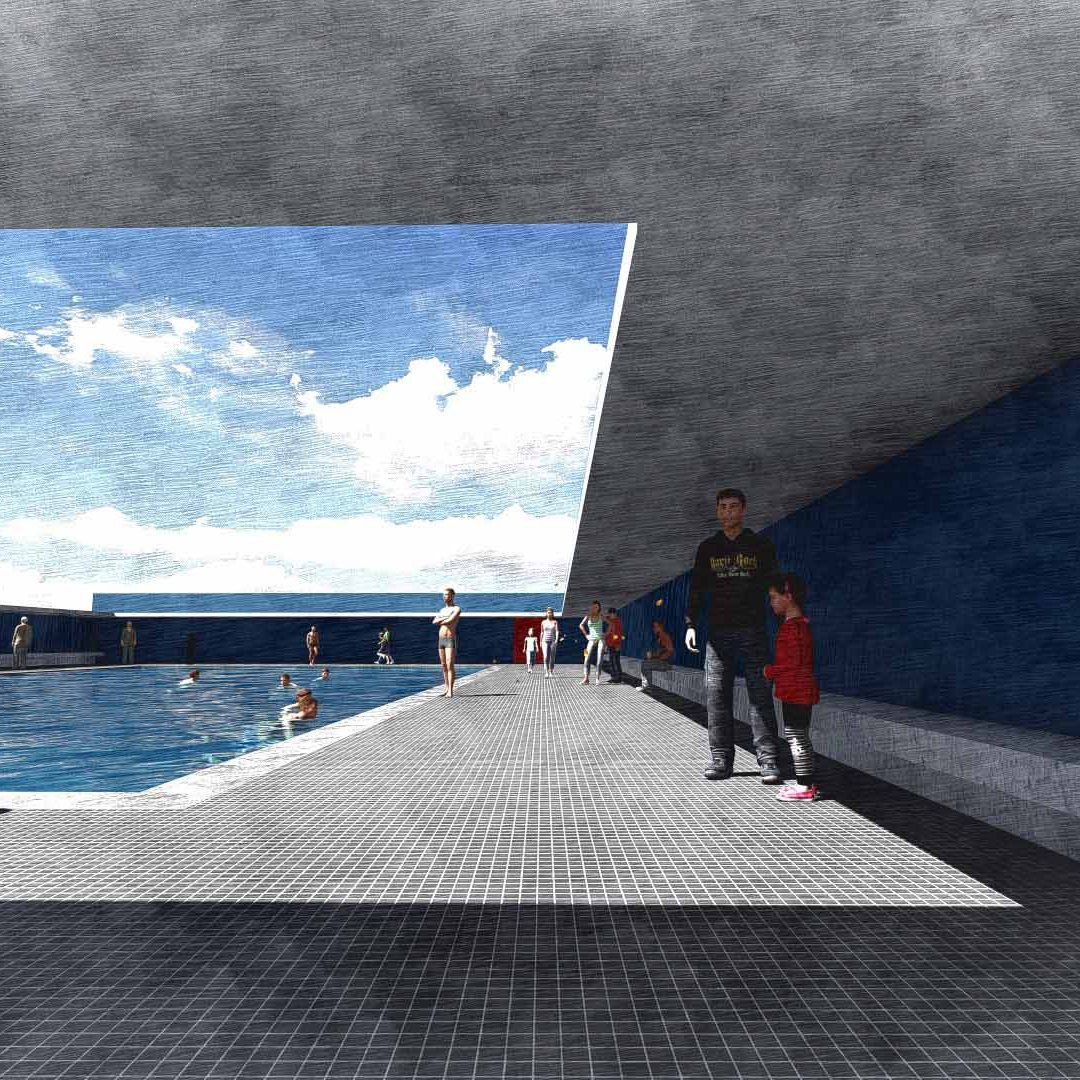

- MILLK – Recreational Centre for Kids and Adults – A place that can engage people of all age groups at a time

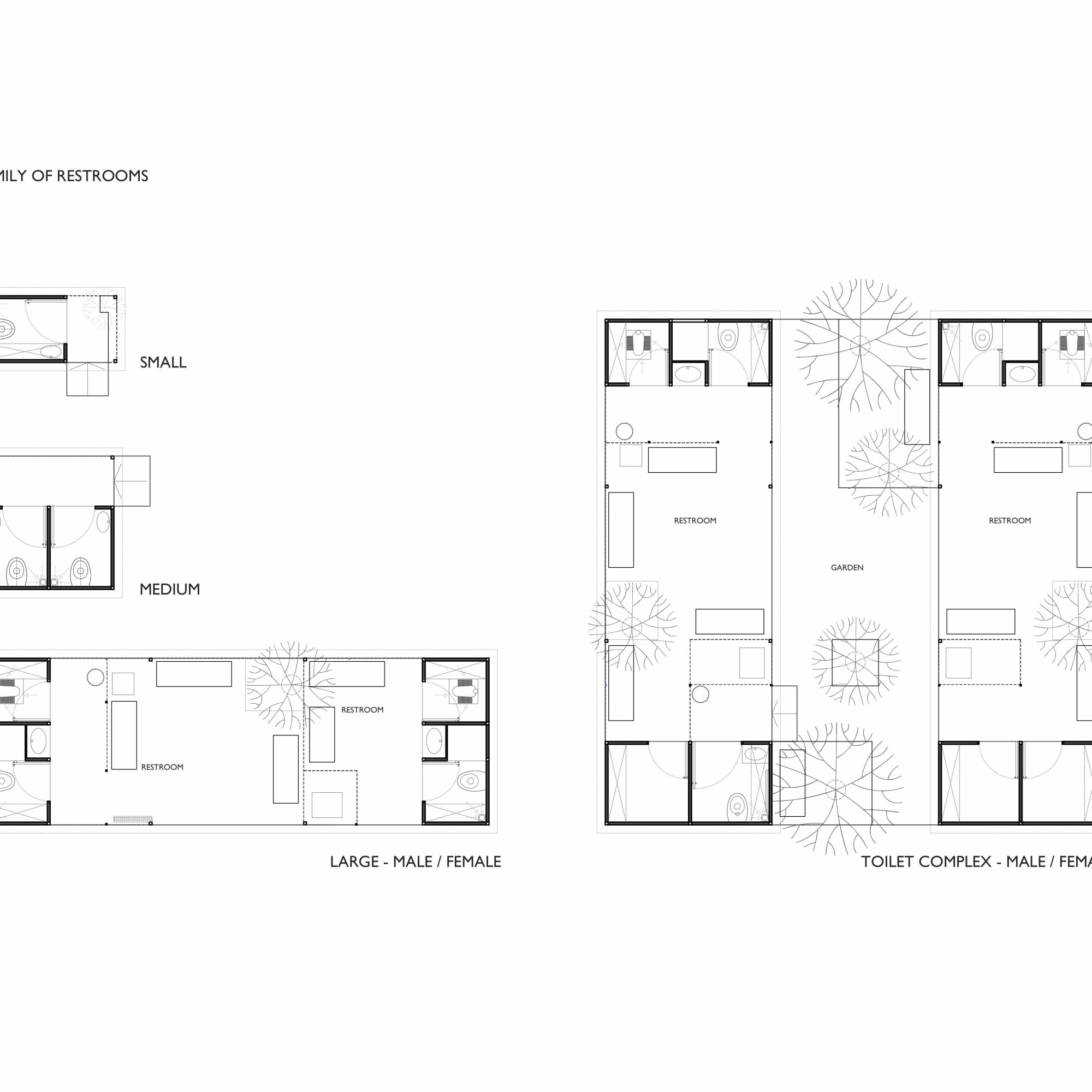

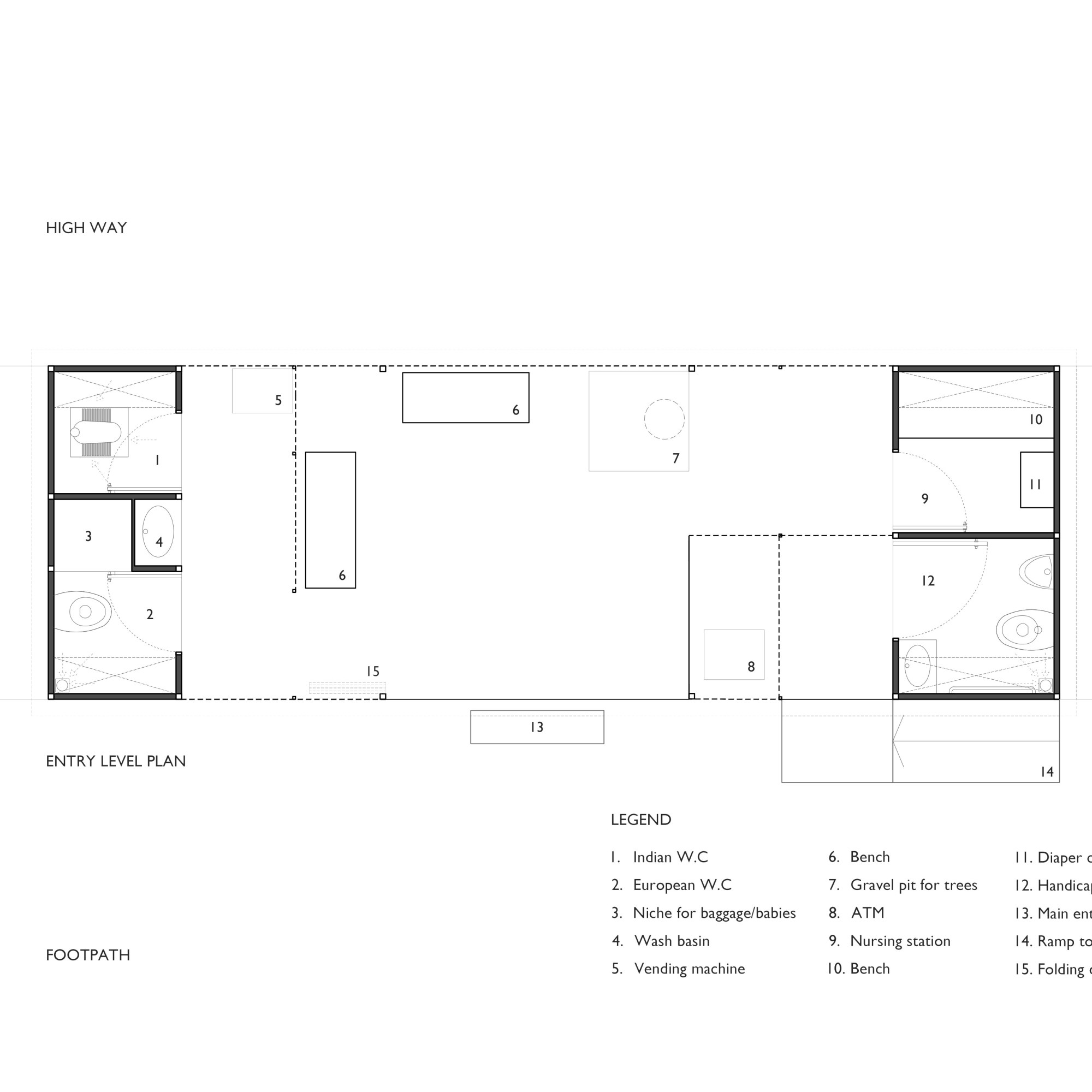

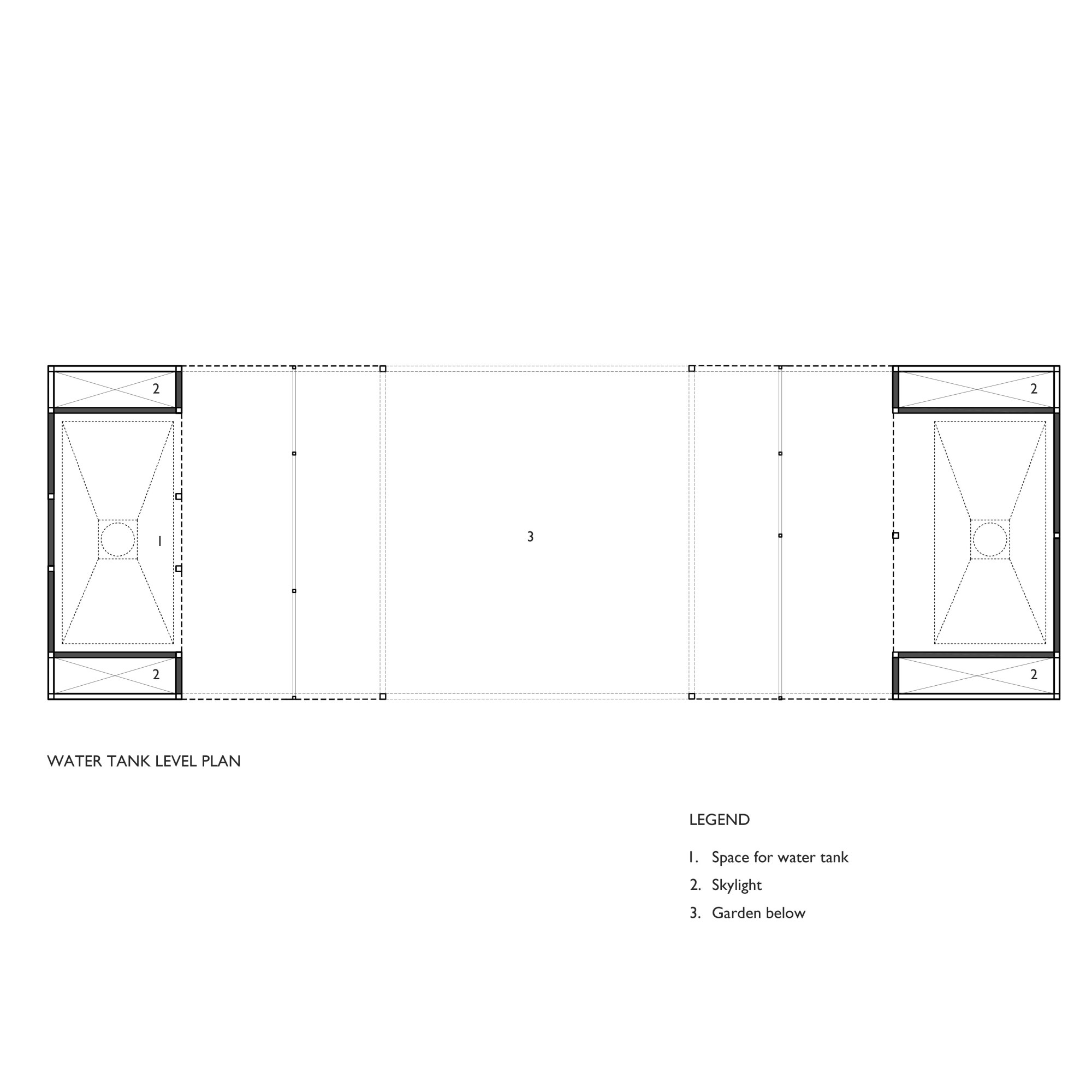

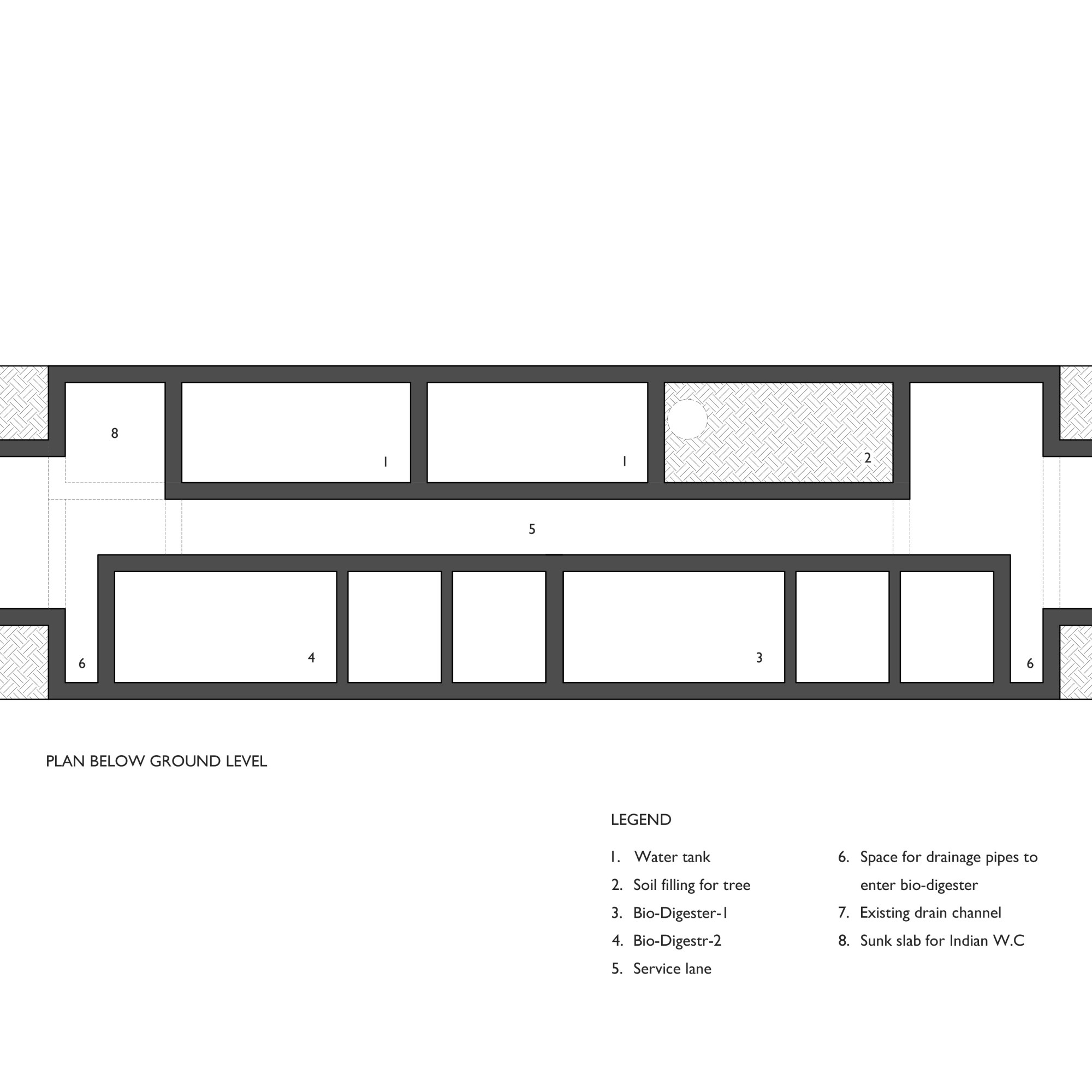

- The Light Box – Restroom for Women in Thane – A public toilet prototype that was replicated in the city in 14 different locations

- The New Research and Resource Centre for UDRI – An additional facility for UDRI for their growing number of books and weekly events

- Framed Habitat – A single family housing prototypes for 2020 that would adapt to climate, family size and activities.

- Modular Habitat – Disaster Relief Housing in Nepal

The ambitions are informed by ideas that we develop during each project and I think it is very organic. With every new project the ambitions are reset as we realise new potentials of our own practice.

What forms the basis of your practice now? What would identify as the main intention of your work? What are the values or principles that the studio is grounded in?

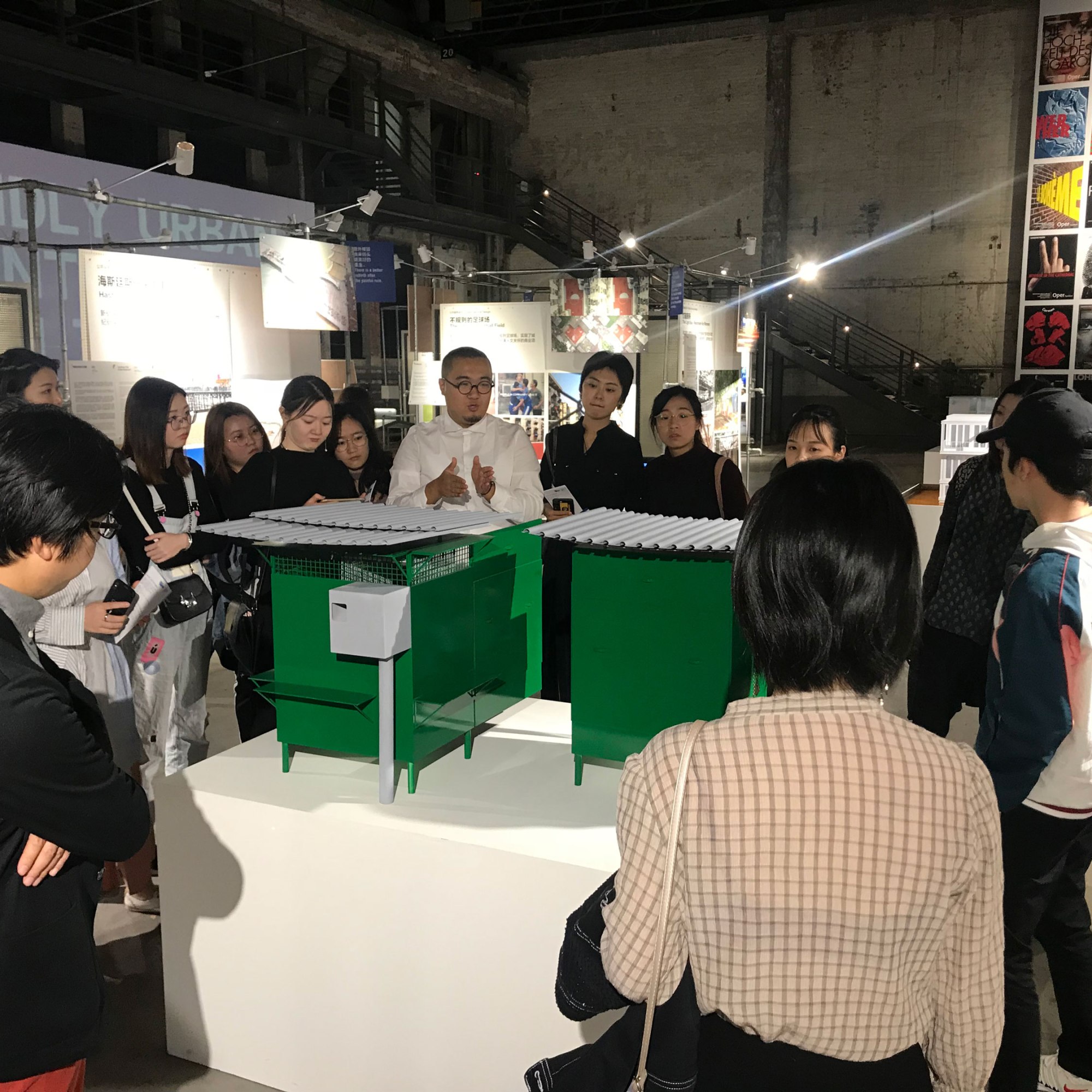

RC: I have always been interested in the idea of a microclimate and its relationship with space and scale. In one of my first international exhibition in Beijing, I had titled my talk as “MICRO” an idea that encapsulates the domestic relationships between space, scale and climate. In every project, we try to use MICRO as a tool to investigate/ address the most fundamental questions. The idea of MICRO varies across projects, in some projects it would be a resting space, or a courtyard or a terrace and this becomes the starting point around which the project is set up.

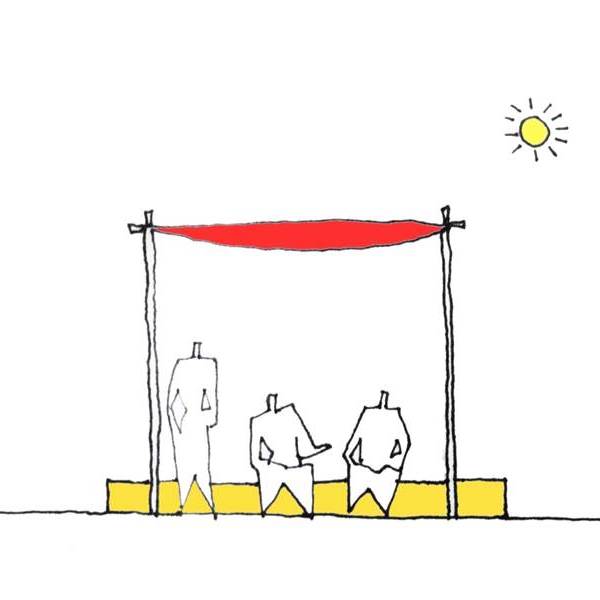

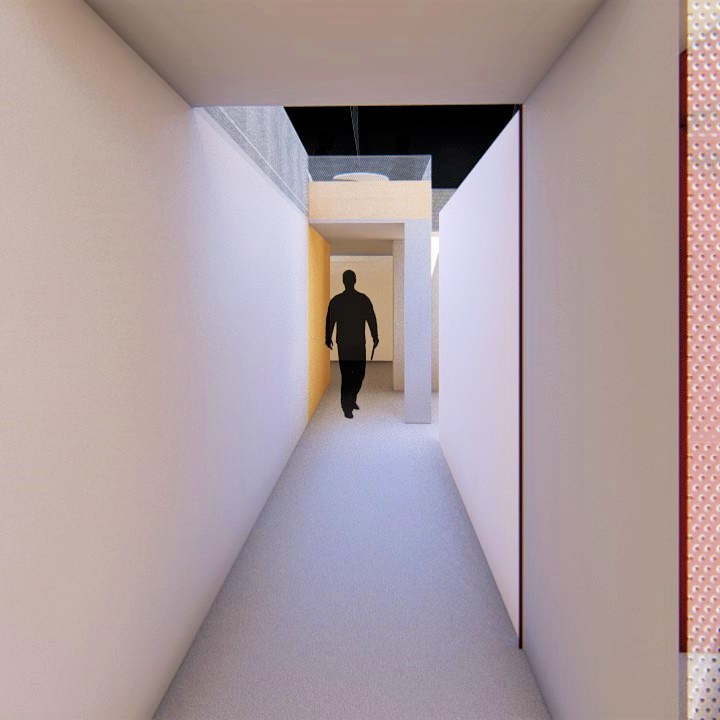

Another important aspect we look at while conceptualising a project is asking the most fundamental questions to the issues that we are looking at. For example: The restroom for women was a simple project to design a public toilet for women, but to me it is very important to express many layers to the idea of a restroom completely than just build toilet blocks. The resting space became the highlight of the project that made this prototype different from the rest. May be such ideas take a project a step further? And the success of a project lies in the answers to these basic questions. Then the kind of materials we used to express light, ventilation and maintenance gave it an expression of “The Light Box”.

The MICRO and the project issues then become the guiding factor for any project we do, but there is one more thing that is at the back of my mind while combining these two aspects and that is the main intention.

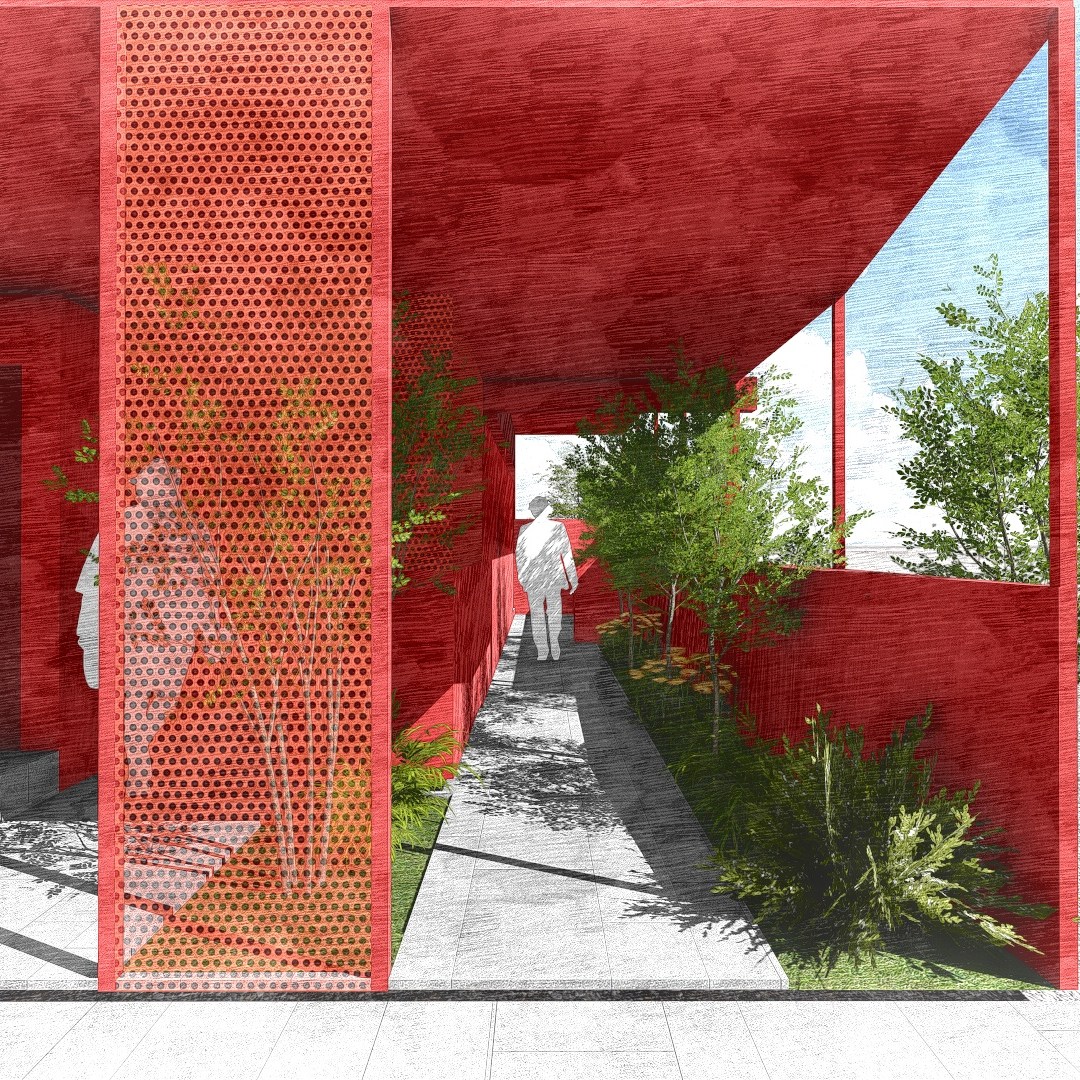

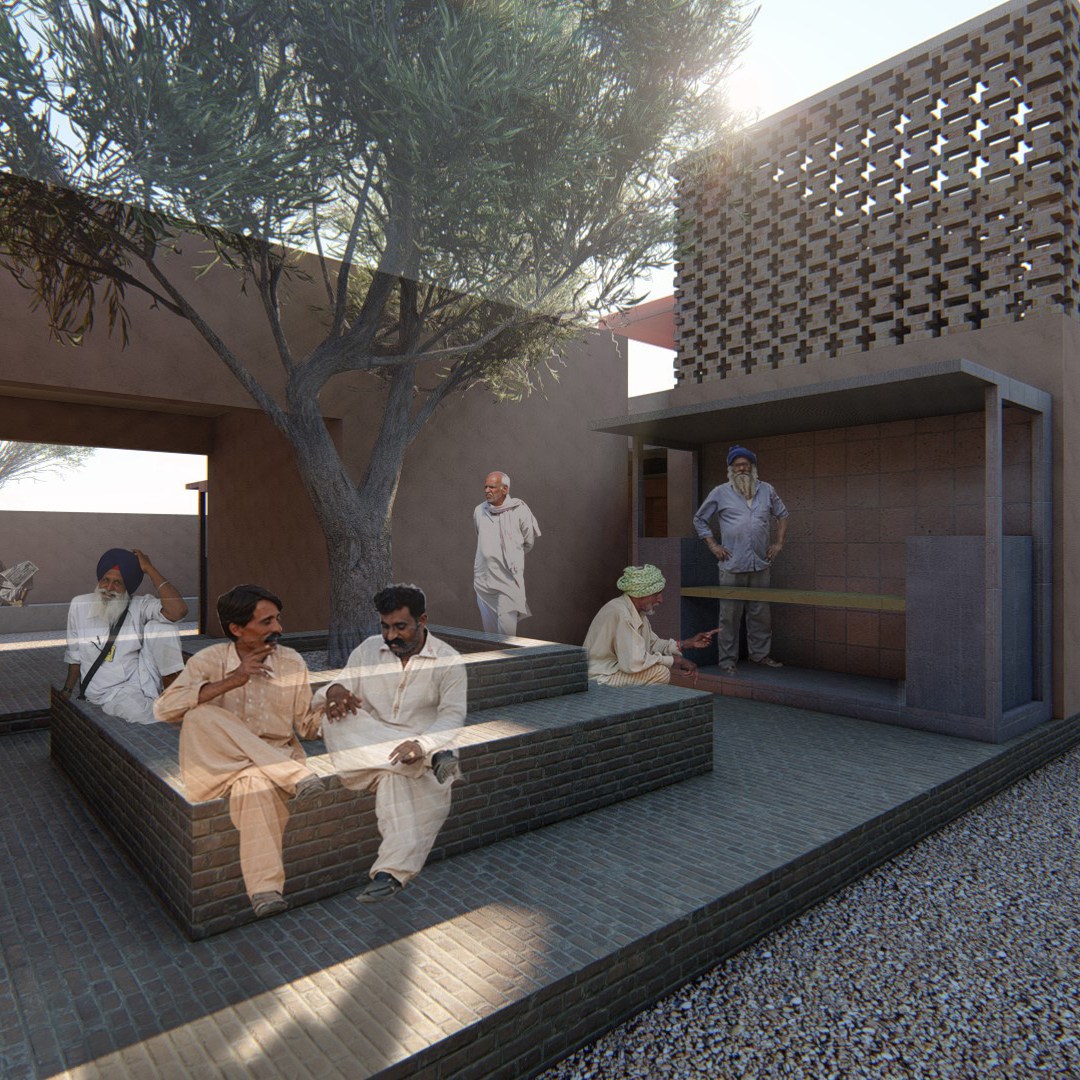

The idea of releasing architecture in a way that it does not come in between man and nature. Architecture as a dialogue generator or a container rather than a performer. This dialogue takes place at the point where man interacts with nature and I do not think anything should come in between them. So how does one create that “Soft dialogue” or that in-between transition where architecture contains man and releases him to the environment that becomes the main intention of the whole process. The soft dialogue then also reflects in all the detail decision making of the project right from selection of materials, colour, furniture etc.

At the outset, how has it evolved, and what is the way forward?

RC: I think the idea of MICRO and questioning the fundamentals has allowed us to investigate into a deeper understanding of the design problem. This process does push our own boundaries and the end results are pleasantly surprising.

When we look at the vernacular architecture, we are able to relate the essence of our work to it, though the materials we use are contemporary but the expression of space feels rooted to the users.

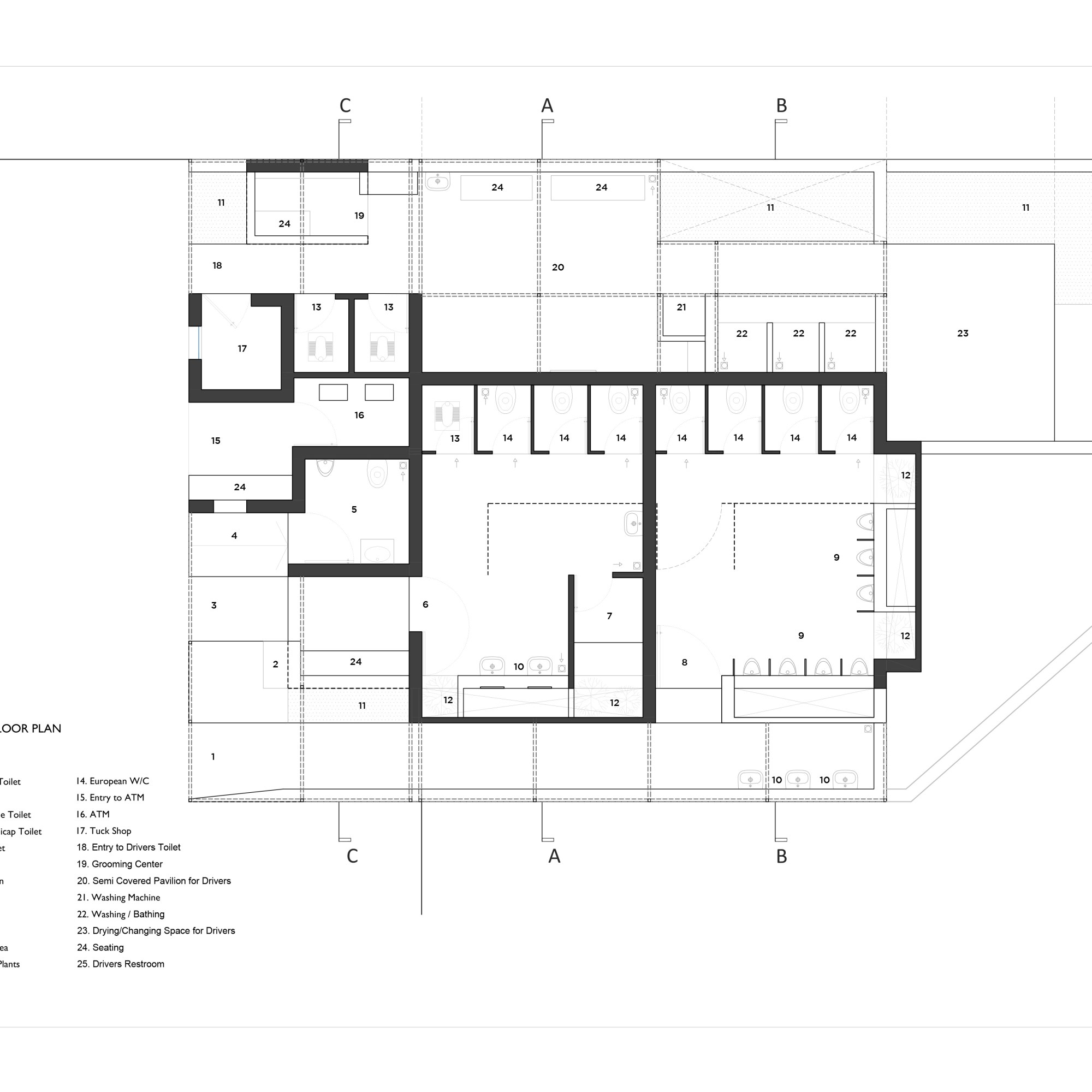

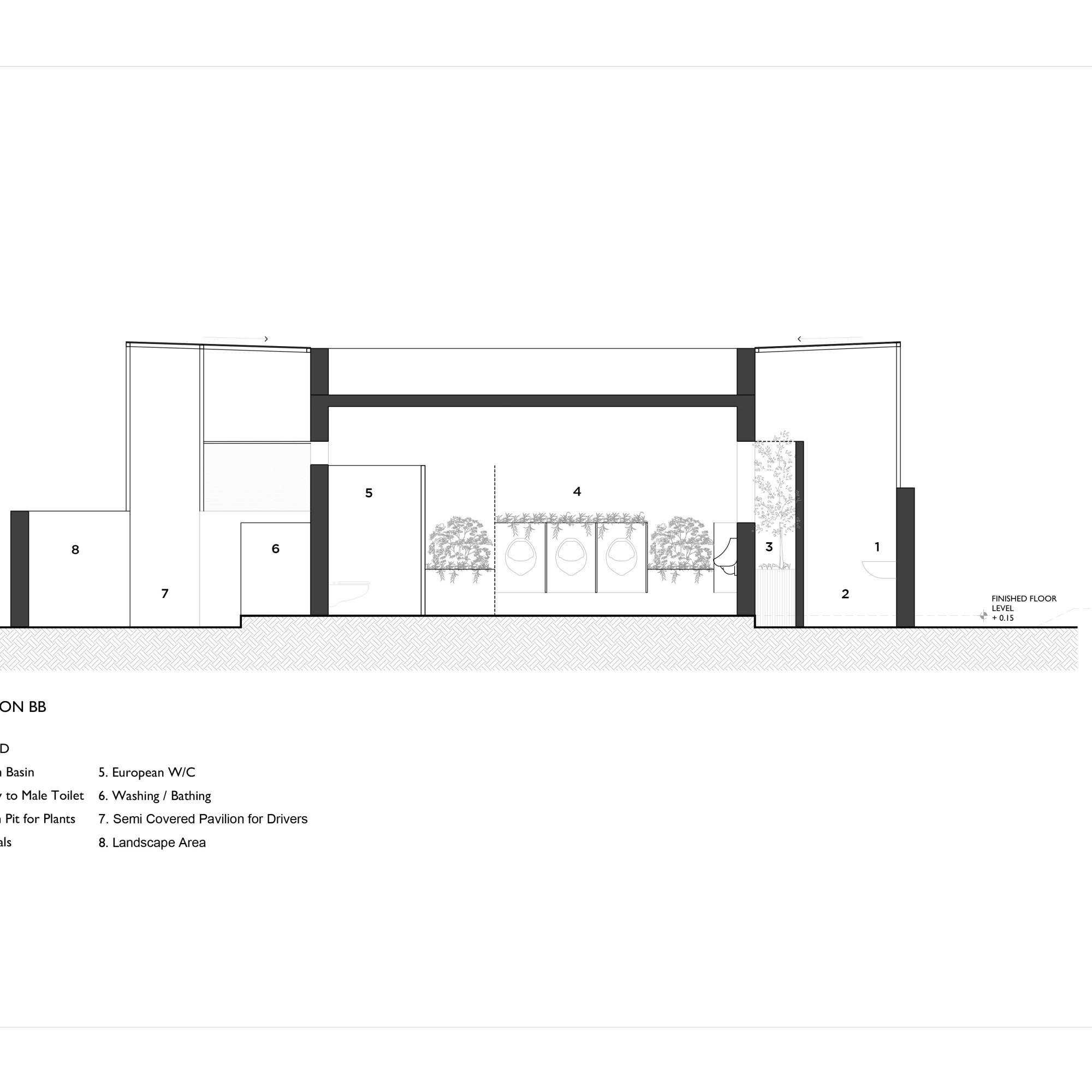

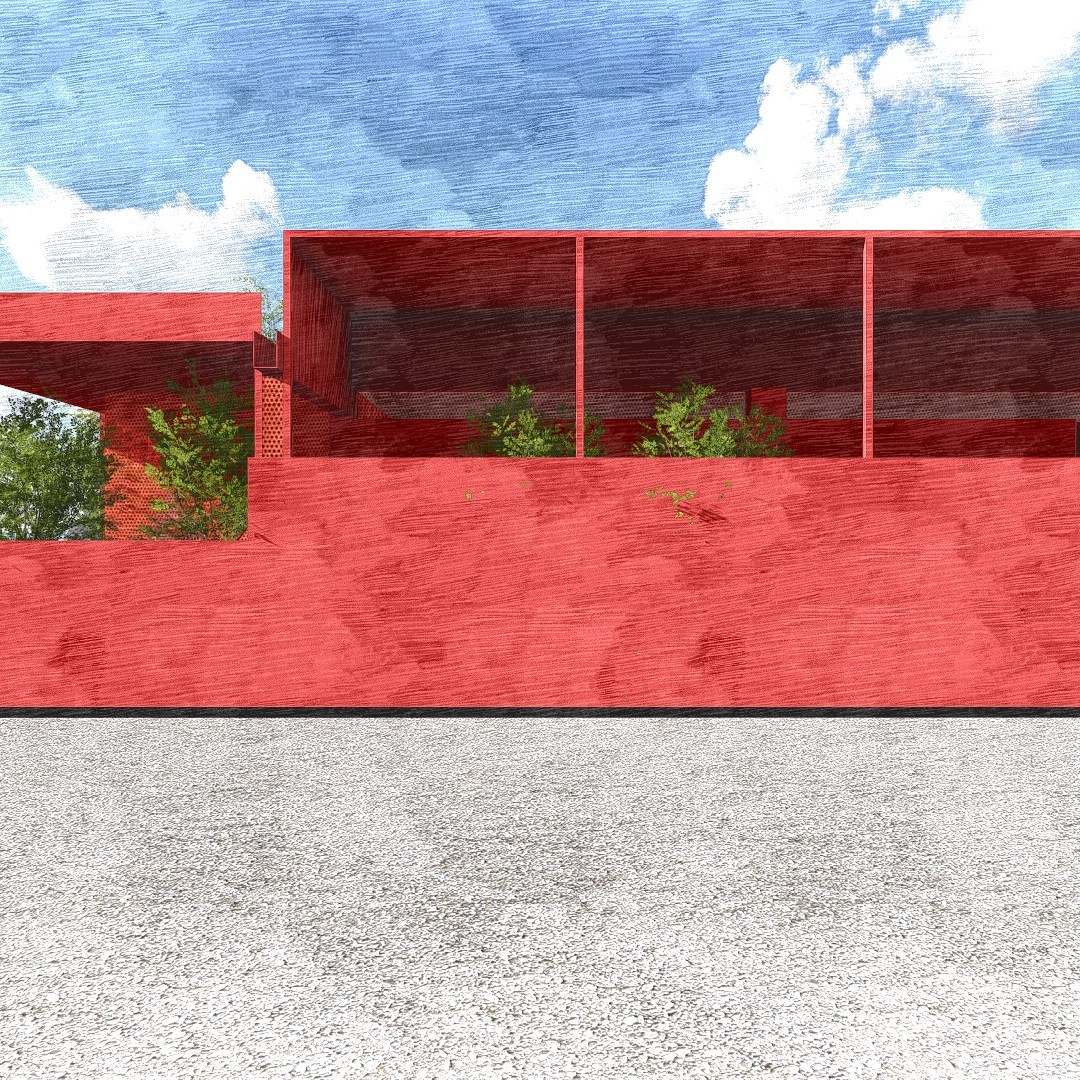

For example: The Pause Restrooms is a stark red contemporary building, after few years I would still find it to be new. But when I look into the nooks and corners of spaces and architecture, I can very well relate it to the domestic nature of vernacular spaces that one can find in a village and I think that is the reason the truck drivers are comfortable in that environment. This is wonderful, the idea of creating a bridge between the vernacular and the contemporary and still expressing what the future might be I would like to term this as “Engineered Vernacular”, the way forward…

What are the typologies and scales that you are currently engaged with? What are your interests and what kind of work appeals to you? What work does your studio actively seek?

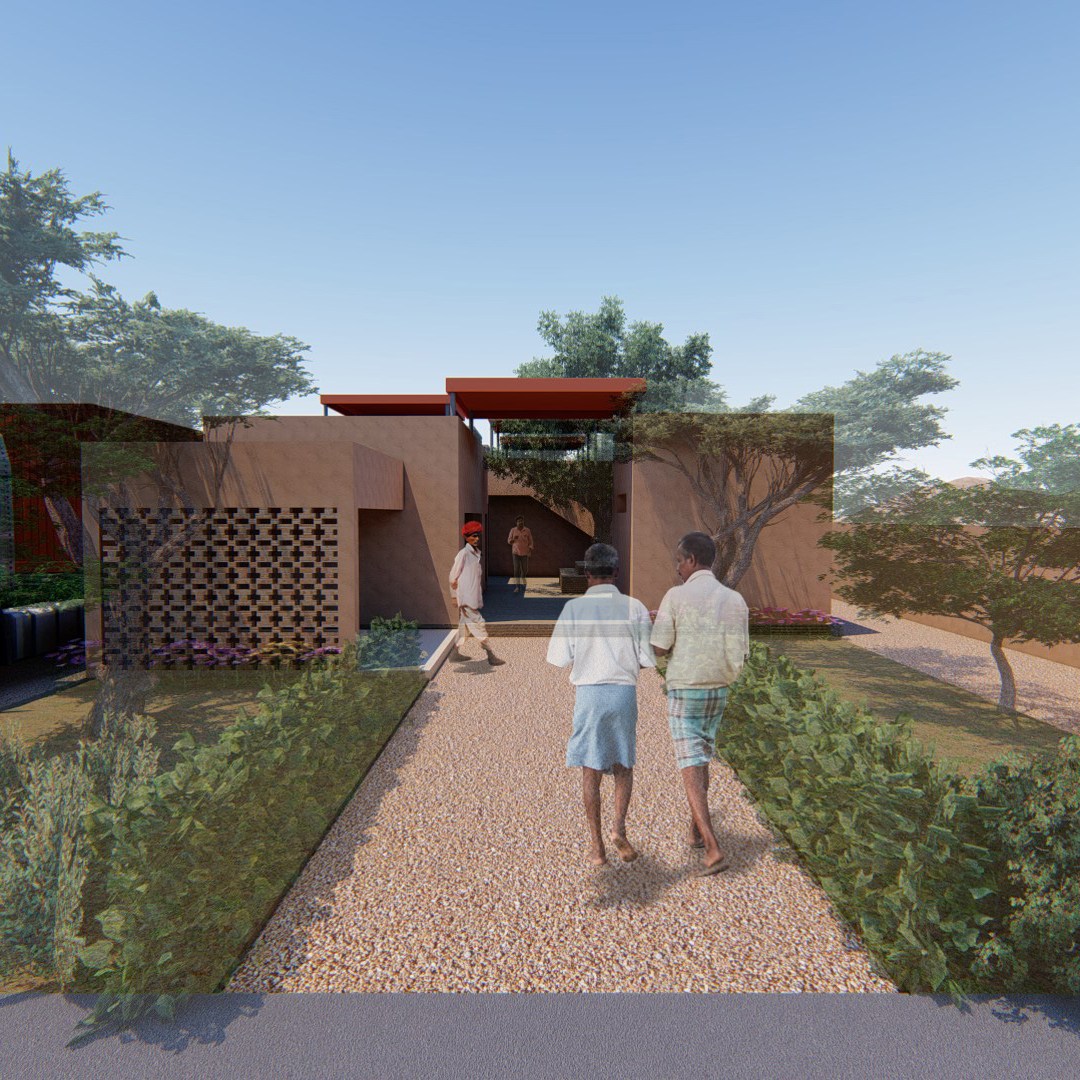

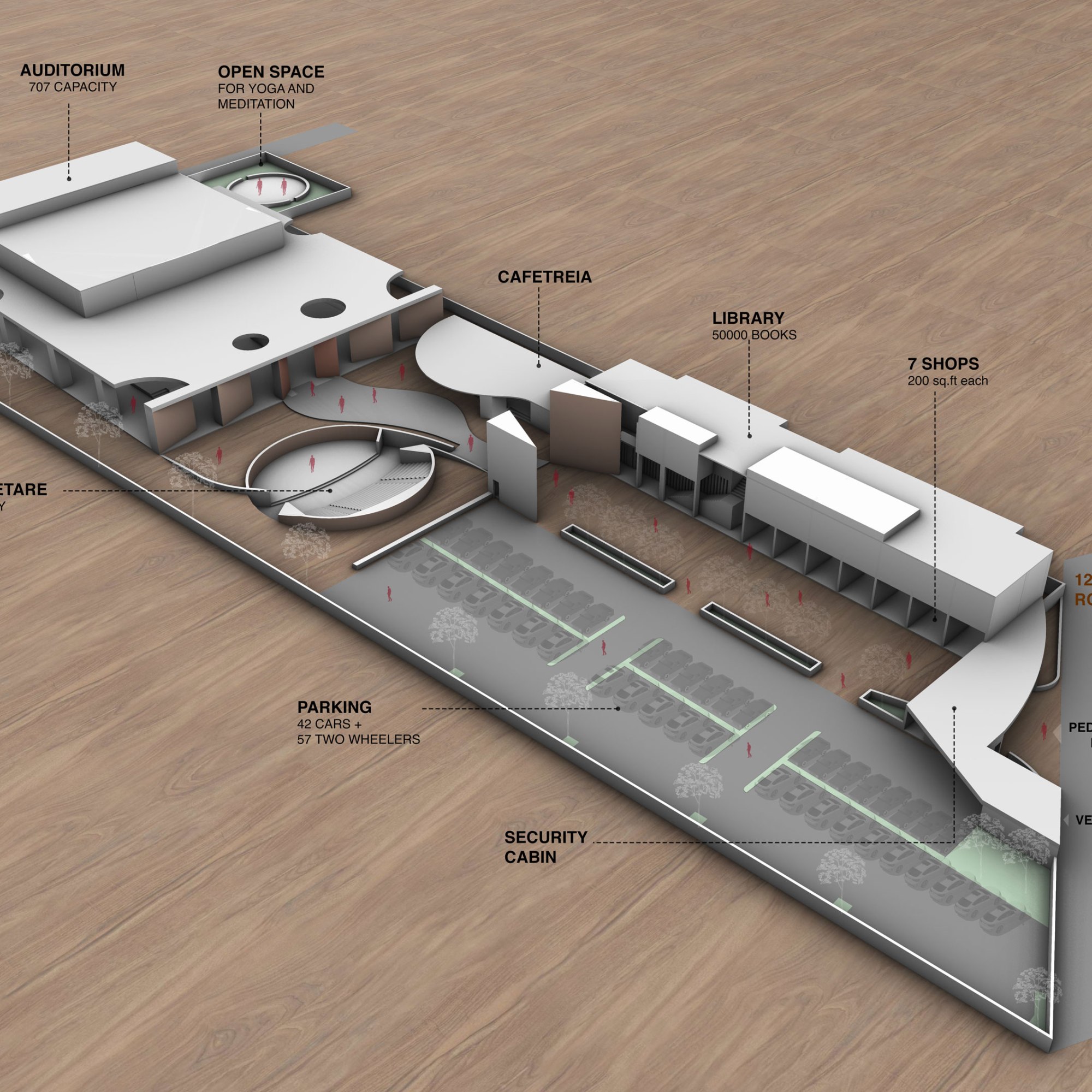

RC: We are currently working on an Affordable Housing in Neral which primarily uses passive lighting and ventilation systems as the main element to configure the design of each unit. A PCB manufacturing unit in Pune that demonstrates the idea of fabrication at a macro level, and also at a micro level where perforated metal screens are used as surfaces for display and utility. Two projects for the truck drivers’ community – one in Chitradurga, that is a village with facilities to eat, stay and entertainment, and other in Rajasthan that is purely a transient housing for their community.

We recently exhibited the Truck Drivers’ Village in an exhibition titled – ‘Design in an Age of Crisis’ at the London Design Biennale. We are working on another exhibition titled Terra that will take place in September 2022 at the Lisbon Architecture Triennale.

We have not restricted ourselves to any kind of typology; in fact, what interests me the most is the situation and the theme of the project. The situation comes out of the design brief and the response to the brief is the theme that we work with.

How did you get involved in such projects in the public domain? How do you deal with projects in the public domain which involve multiple agencies and expectations?

RC: We never had a plan to get into public domain. I think it all came together when the Government launched the “Swacch Bharat Abhiyaan” as a result of which the NGO Agasti initiated the project, and we pitched for it with our designs of “how a toilet should not only serve its primary function but go beyond the brief and explore many possibilities of being a toilet”. That is where our journey started in public domain.

The next project we did was the “Toilet in a Courtyard “for the Western Railways on Platform 1 at Bandra Station. After these two projects, a private client approached us to design the Pause Restrooms and this chain led to many other commissions. We are currently building a Village for Truck Drivers on a 2.5 Acre land on the Pune-Bangalore highway and another one in Rajasthan that is yet to begin.

Cost is an important factor while working with public domain. So, we constantly question, “Is it required?” If you see all the infrastructure projects that we have designed, they never have a 10-foot ceiling height. We try to optimise it by keeping it at 7’6”.

We do have fixed budgets and we have to work within that. It is a constraint and I think that is what allows us to innovate. Through design we are trying to guide the users to use the space in a specific manner; for example, in toilets we never provide windows but have skylights that are mechanically ventilated. Through research we realised that in public toilets windows are stuffed with gutkha packets and sanitary pad wrappers, with no windows and only skylights that are beyond the reach of the users the only place one can throw the waste is in the dustbin inside the toilet – we hope they do. But we try to imagine such situations to bring some civic sense to the people. The reason why people do not loiter on the airports is because a common man feels a sense of respect with those facilities; it is like someone serving you a five-course meal. The same person feels exactly opposite on the train stations or public toilets, a sense of disrespect. I think that is the difference – it is like Newton’s 3rd law “Every action has an equal and opposite reaction”. It is like what the city gives its citizens they will receive the same in return; if you give garbage, you will receive garbage.

What is the nature of the design and thought processes pertinent to your practice? What are the tools of your practice? How have the processes evolved over this decade? How does the studio participate in this process?

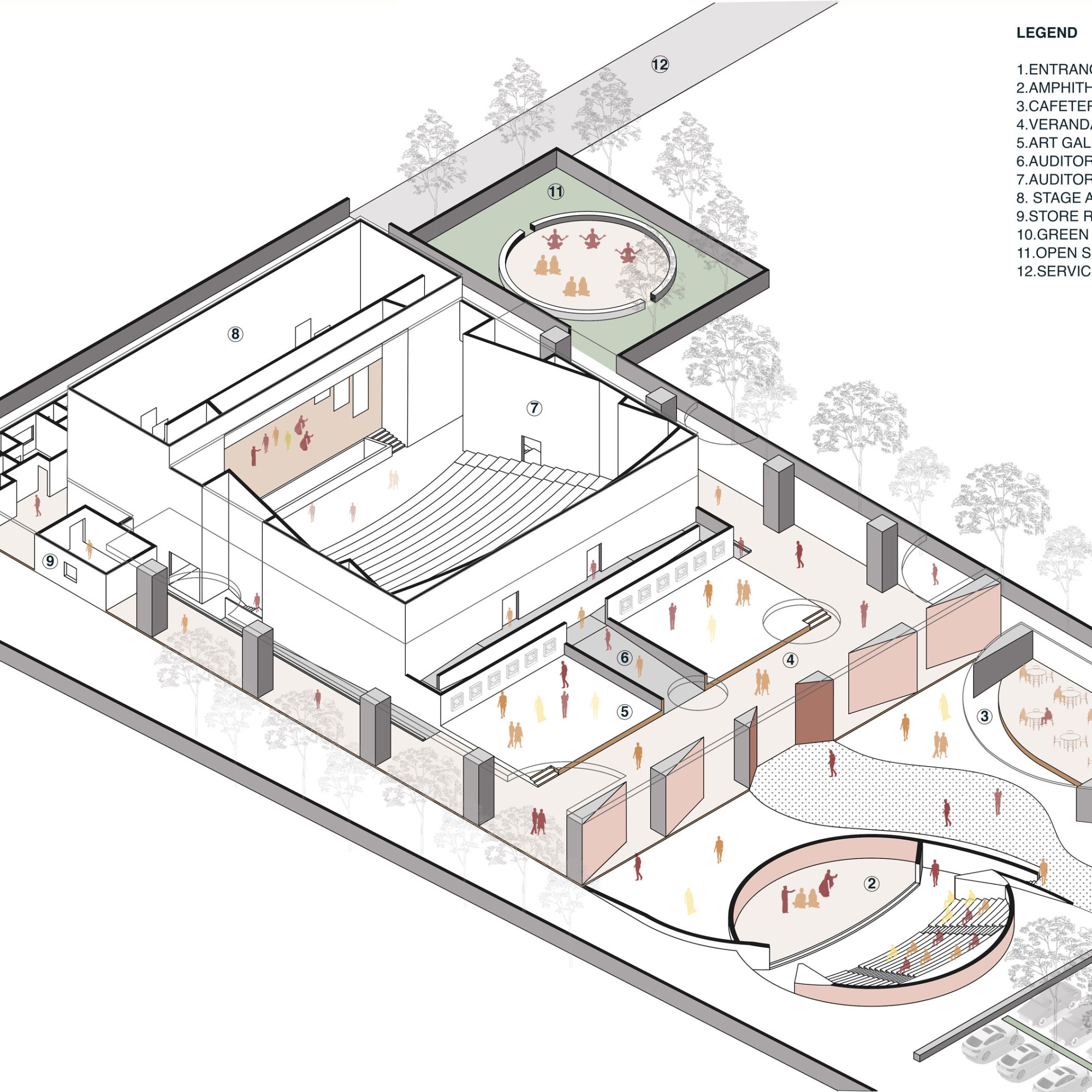

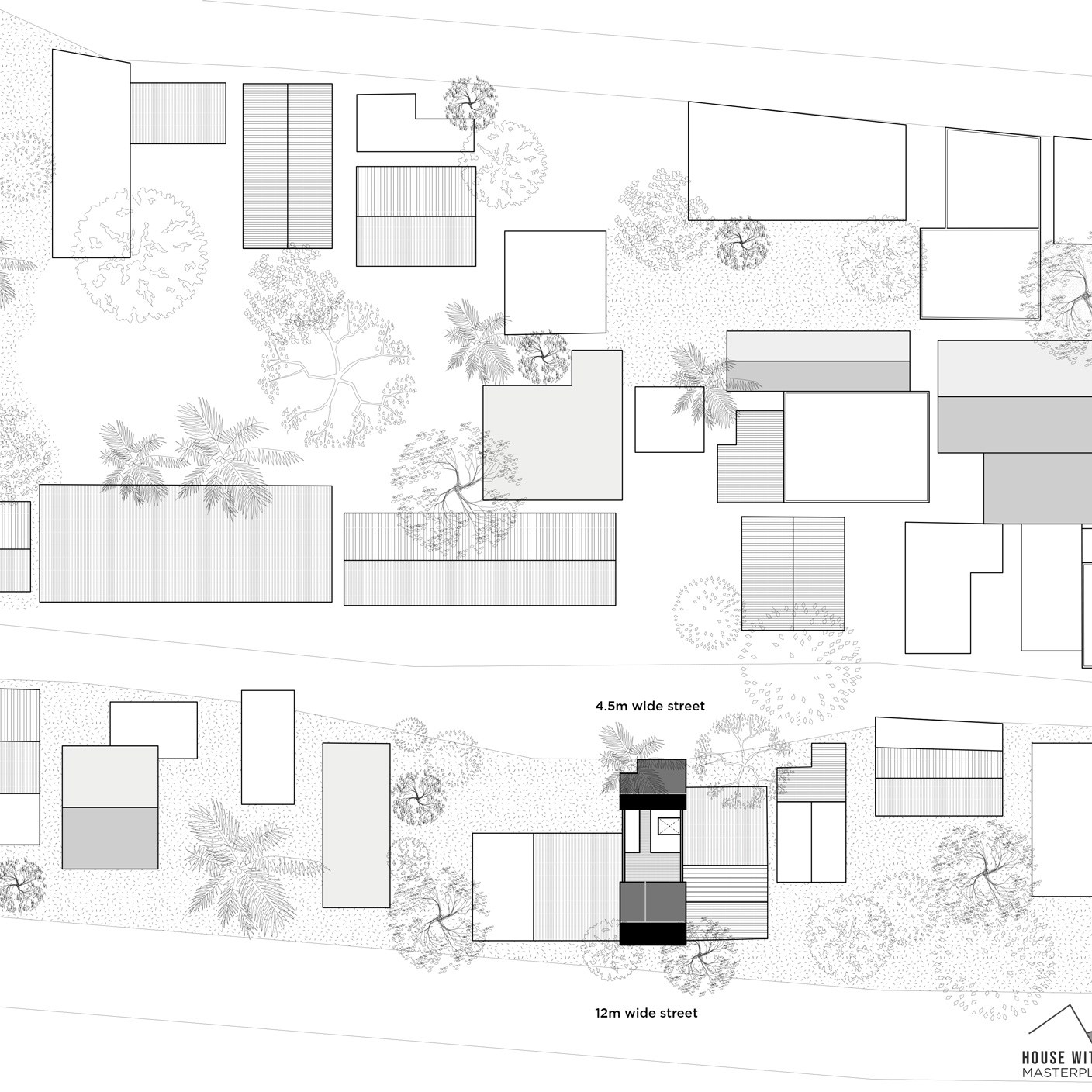

RC: As a thought process we start with a lot of basic thinking, we create diagrams to scale of arranging spaces, more like space management studies. These studies reflect the overall fabric of the project that documents open, semi-open and covered spaces. The organisation of these diagrams is based on the conceptual idea and the project intent. But at the same time, we are exploring MICRO and raising the fundamental questions related to the design problem, along with studies of spaces at eye level. According to me, it is very important to understand what is happening inside the building, for then it becomes quite easy to control the mass from outside.

Within the studio, we compare and discuss all the studies that help us analyse which diagram works the best as a conceptual idea and with the project intent. We then share these diagram studies along with some basic set of renders for each study with the clients along with our preferences to get their reaction. In this process, we understand what works the best, and then we further start detail designing on the preferred diagram or we do a combination of two or three diagrams etc. The diagram study method has been consistent since day one which we even follow today, it gives us a lot of clarity in understanding on the proportion of built mass that we are dealing with.

One of the consistent lines of enquiry you have maintained is to locate your work within the public domain and community-level projects. What are the factors and challenges that affect such a pursuit?

RC: Yes, we have been quite fortunate to locate our work in public domain. A challenging aspect about working in public domain is that there is no fixed client – there are people of different age groups and genders using the space. The design has to be done considering various possibilities of space usage, and there is immense imagination one has to go through while making detail decisions.

The other challenge I see working in the public domain is community mobilisation or convincing the property owner along which the projects is getting built. No one wants a public toilet-built right in front of their house or their property. Then how does one convince the owner? In our country the notion of public toilet is so bad even if we show good designs to them, they do not believe it.

During the construction of Toilet in a Courtyard, every night the slum dwellers along the Bandra station had dinner parties in the courtyard at night, they would spill food all over and use all the facilities without flushing. This repeatedly happened even when our project was abutting the police station!! Every morning, the poor contractors would have to clean the spaces and then start their days work. Taps, tube lights would get stolen, and many such small equipment. We asked for police security and that is when there was a smooth way to work on site.

We had designed a ‘Slum Sanitation Program’ for the slums in Kalwa. The design got approved by the TMC, the budget got approved but the slum dwellers were not ready to get it built so it got shelved. We tried to involve some experienced officials to mobilise the community but it did not work. One thing I have realised, the slum dwellers are always worried when people like us approach them, because even when we have good intentions they think we have a hidden agenda with which we will operate later. That is the reason for their resistance which is totally valid, according to me. I have seen the way they live in the household and sanitation is in a very bad state. Only they themselves have the capacity to better their own positions or they need a leader who can convince them what we are doing is for their betterment.

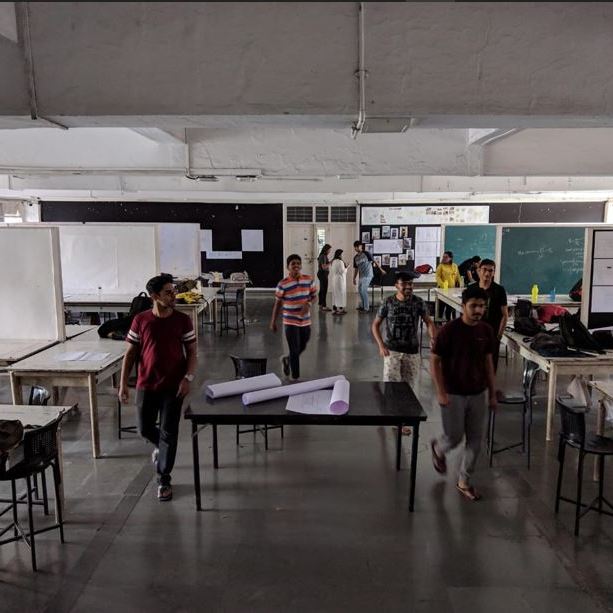

What is the studio culture and dynamic like? How does your studio participate in the process? What kind of environment and scale do you imagine this sort of practice to have further?

RC: I think any project is built with many ideas coming from various sources. Ideas come from clients, fellow architects, interns, contractors, masons, carpenters on site etc. In this situation the concept and the theme become an important guiding factor to align all the ideas together. I believe in this kind of a practice, something I learnt from Charles in my early days of working. In the office, he would ask everyone their opinion no matter how naïve we were. I think he felt in every opinion there is an idea, I may be wrong but that was my reading of him.

The studio is very democratic in that sense, if you see architecture is also a democratic art when one is working in the public domain. We are not sure who the user groups are, so one has to design for a universal condition and that I feel is very challenging. For example, a house is an aspiration of a family of four to six and those aspirations are pretty much informed by the client. A public project is an aspiration of the city and these aspirations are not informed by anyone. The architects thought process becomes important and he/she is responsible for creating those aspirations that work for the city. In this situation the architect may succeed or fail.

Are there any influences you see from the teaching/academia you are invested in?

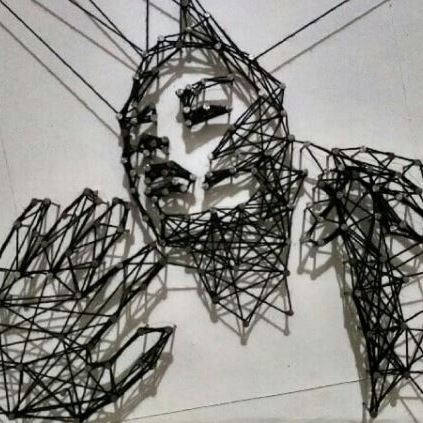

RC: I think teaching helps to validate my own thoughts. In academia, there is a lot of conceptual and thematic thought process which I try to pull towards reality. In this process, the students push their boundaries of thinking and analysing their own ideas. In practice, I try to do the exact reverse where the reality is pushed to a more thematic and concept-based approach.

I think these two approaches help maintain a balance between thought and execution.

What is the aspect of work that you value the most? What are the critical parameters of a project that make it successful for you?

RC: I think “honest expression” is something that I value the most.

It may be the honesty of intention of creating a space, or an honest expression of material, structure, or the complete honesty with which the building is crafted using local materials and labour. For example, we are doing one house in Pune on a sloping site facing the valley; for me, the truth of that site is the journey where one starts descending down the slope of the land and reaches the edge to see the valley. The house should inhabit this journey, the movement and the view, that becomes very important as a concept. Or in the Truck Drivers’ Village, the truth is the kind of spaces the user group inhabits, the materials that they feel comfortable with or the kind of openness they experience when they are at home. I think the success of architecture lies in these aspects.

Where one is honest in the complete process of a project where one does not have to play any special tricks to make a project successful, the project succeeds by itself.

Where do the challenges of your practices lie?

RC: To create architecture that is true to its intent and the site is the greatest challenge that we face and that is what we try to do in each project.

What is your reading of contemporary architecture in India? How do you seek to position your work and your practice within the larger conversation on architecture in India?

RC: I think in India the contemporary architecture is moving towards the idea of craft and working with locally available resources. As a result, we see a lot of architects breaking out of their own style and producing projects of a different quality. This is also pushing the architect to think differently and come up with new details and a new design language that is not standard to their practice.

I am not sure how would I seek to position my work; instead, I would say if my projects are doing justice to the space and the intention for what it is built for and at the same time, I am able to bridge the gap between the vernacular and contemporary. It is important to have an architecture of our own, an architecture that belongs to us without which there will be no culture or identity. Only machines are culture-free, life of people revolve around culture and religion ♦

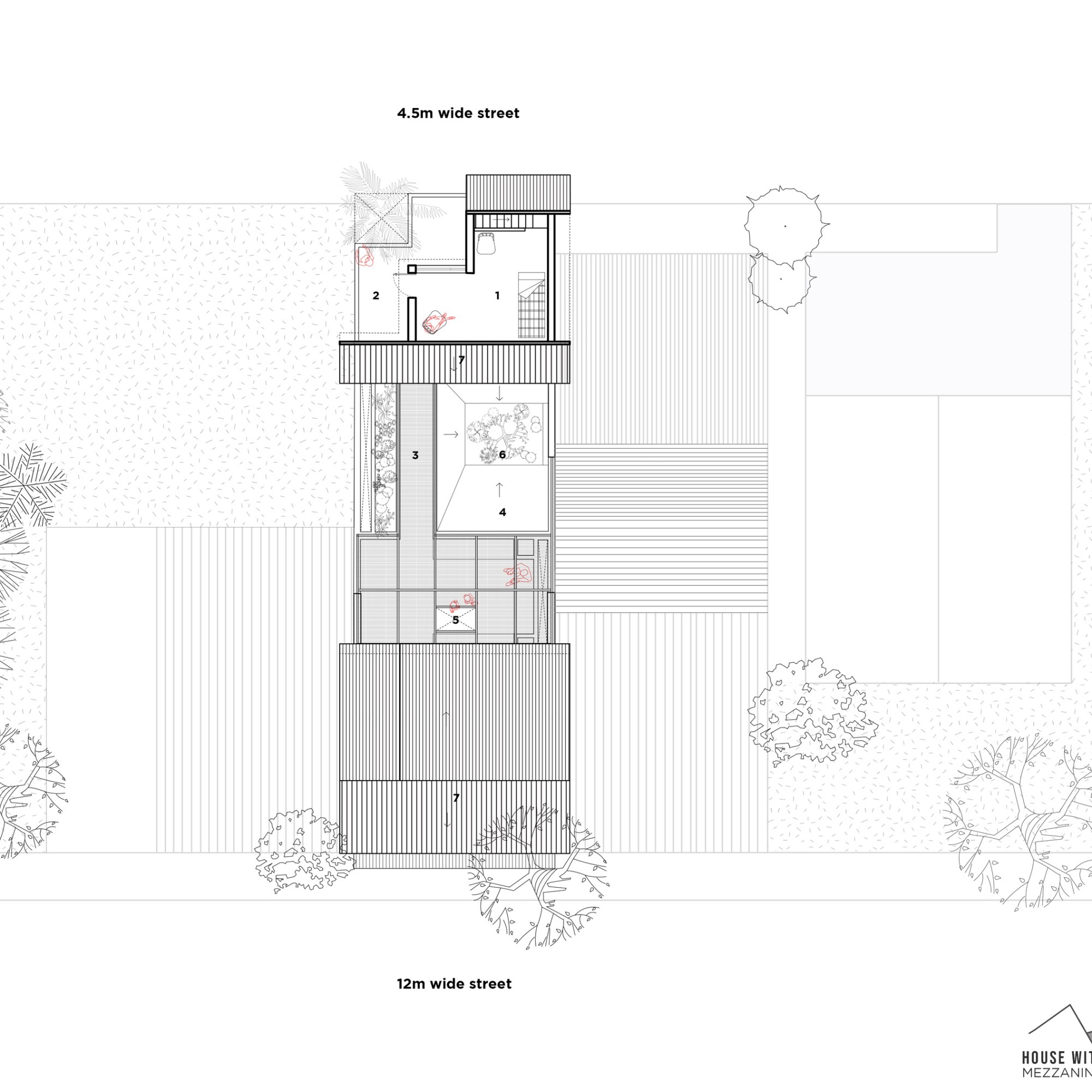

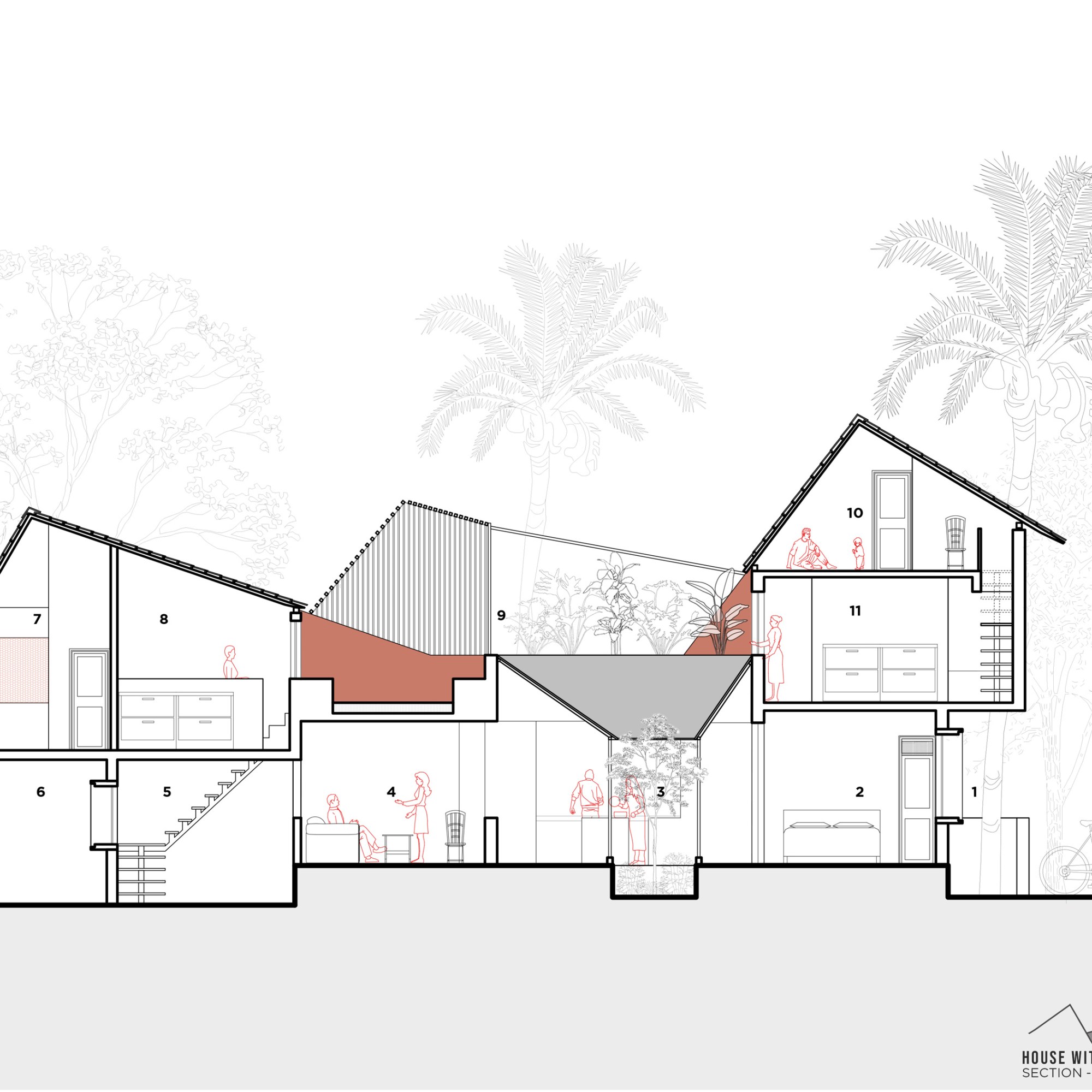

Images & Drawings: courtesy Rohan Chavan, © RC Architects

Filming: Accord Equips | Editing: Gasper D’souza, White Brick Wall Studio

Praxis is editorially positioned as a survey of contemporary practices in India, with a particular emphasis on the principles of practice, the structure of its processes, and the challenges it is rooted in. The focus is on firms whose span of work has committed to advancing specific alignments and has matured, over the course of the last decade. Through discussions on the different trajectories that the featured practices have adopted, the intent is to foreground a larger conversation on how the model of a studio is evolving in the context of India. It aims to unpack the contents, systems that organise the thinking in a practice. Praxis is an editorial project by Matter in partnership with Şişecam Flat Glass.

Şişecam Flat Glass India Pvt Ltd

With a corporate history spanning more than 85 years, Şişecam is currently one of the world’s leading glass producers with production operations located in 14 countries on four continents. Şişecam has introduced numerous innovations and driven development of the flat glass industry both in Turkey and the larger region, and is a leader in Europe and the world’s fifth largest flat glass producer in terms of production capacity. Şişecam conducts flat glass operations in three core business lines: architectural glass (e.g. flat glass, patterned glass, laminated glass and coated glass), energy glass and home appliance glass. Currently, Şişecam operates in flat glass with ten production facilities located in six countries, providing input to the construction, furniture, energy and home appliances industries with an ever-expanding range of products.

Email: indiasales@sisecam.com | W: www.sisecamflatglass.com

Very nice interview.