An editorial project by Matter in partnership with Şişecam Flat Glass, PRAXIS investigates the work and positions of diverse contemporary architecture practices in India. This episode features a discussion with Varna Shashidhar of Bengaluru-based Varna Shashidhar Landscape Architecture [VSLA]. The practice of VSLA develops from a contextual ethos of approaching and representing landscape from an integrated and multidisciplinary perspective. Through projects and research that traverse scales, their work centres around “beauty in the ordinary”. Varna elaborates on envisioning designs that develop over time and terrains and working in harmony with endemic ecosystems that form an underlay to their process. To advance collaborative cultural production, she also speaks of founding Design United to enable dialogues and a palpable sense of collectivity.

EXCERPTS FROM THE INTERVIEW:

VS: Varna Shashidar

FOUNDATIONS

<00:31>

VS: My journey into landscape began with my architectural studies. During the final few years of my studies, I had the opportunity to work with architect Anjalendran C in Sri Lanka. That was a transformative part of the experience for me because for the very first-time architecture or design meant really experiencing places. It was a very broad, far-reaching internship, where it exposed me so much to not just architecture but cultural landscapes, archaeology, ideas of history, music, and to some works of fantastic architects, such as Geoffrey Bawa.

I think this was where I discovered my love for landscape and began to really understand an architecture which was very much about a symbiotic relationship with the environment and its context. This broad, well-rounded internship which I would wish for everybody, got me interested in landscape.

VS: Post my internship and completing my studies in architecture, I had the opportunity to study at The Harvard Graduate School of Design, and that has also essentially shaped the way I think, and it has really influenced my practice, because studying at the GSD meant a very multi-disciplinary approach to design, and I enjoyed it tremendously. It meant fantastic friends, fantastic mentors, and also learning from scientists, ecologists, people who were at the cutting-edge of the discipline. For me, studying at the GSD and spending time in Sri Lanka meant looking back at our own country from a different perspective, to really examine things that I had always taken for granted and recognising the beauty of what we have. That very much set about the course of what I wanted to do; it was very clear that I wanted to come back to India to establish a practice.

<03:30>

VS: I was mentored by a fantastic mentor Margie Ruddick, a landscape architect, who has now worked in India for about 20-25 years. The connection she has with the Western Ghats, where she has been working, and really understanding places as an outsider and bringing to it a lens which dealt with much more beyond the project; such as with her current work with One Landscape, looking at conserving landscapes from a larger perspective. All of these have had a significant influence on me and practising in the US, with firms that dealt with public environments and parks, like MVVA and WRT were also very influential for me in terms of thinking about how I wanted to practice when I returned. I was very clear that my ideas of practice were very much going to be formed by my quest for what I believed in.

The beauty of India and the beauty of South Asian landscapes are so much about experiencing the extraordinary in the everyday ordinary.

Whether it is a pilgrim who goes on a path of pilgrimage, through these spectacularly composed landscapes, which are not only felt experientially or sensorially. It is even deeper; it is almost to the human consciousness, the ideas of walking barefoot on this beautiful path that sort of changes, looking at a landscape that is actually so connected to the earth but reveals at different points through these moments of journey. Something that goes beyond just the sensorial. […]

I do not want landscape to be a motif of something that it is located in but more so the essence. and always the quest has been to rigorously understand a place and the process of making. This is equally important. Even ten years down the lane, there is so much to discover in our own context and I am so happy with the opportunities I am receiving. […] It is a journey and learning for me, and I suppose that is what I want to keep alive, discovering more of a place and learning how to respond more sensitively.

CULTURE

<06:23>

I love landscape for the fact that it is so collaborative, and I love collaborating with different designers and the opportunity that it affords you to collaborate with architects, various designers, structural engineers and incredibly talented people.

VS: Our studio has always been very small and I think I also worked in very small practices – perhaps, the first practice that I worked with was a verandah practice, with Anjalendran C. I see the benefit of a practice like that, because you are closely integrated with whatever you do, and so closely connected with the site, it has continued to influence how my practice is shaped. My practice is perhaps not a verandah practice, and it started off in a garage and is still very small. […] Developing the design with my practice in itself is small and I would like to keep it small. It began with me and two other team members working together. I would still like for it to be very much hands-on, to afford me the opportunity to be involved in every phase of design and also to take it to the site and personally be connected with it. The team is never more than four but the fact that we collaborate so closely with other offices, sometimes the boundaries blur and I like that very much. Occasionally, the size expands during summers, when we have summer interns joining us but otherwise it remains three-four at the most.

The process is also set up in a similar way because we are thoroughly involved in understanding systems and rigorously studying site and context, the process always starts with that and then come the collaborators that we are collaborating with. […] This mutual learning almost makes it seem like our team has expanded, and there is always this back-and-forth dialogue and our projects are also chosen for this purpose.

The idea starts off, but we are always working with research together, we are trying to explore what the site is, we come together and understand the site more but we are also very informed by the site. This also comes from the background of having worked outside of India, but in a familiar context, but also being in a rigorous academic environment which is based strongly in research and to practice in a way that one is looking at a problem from a research perspective as well. It is a nice intermingling, looking at research as a combined practice but also being very hands-on, which architecture allows you to do.

PROCESS

<08:51>

VS: The kind of work that really appeals to me is anything that is very challenging, that looks at being very careful with resources and the environment.

The overall objective of practice is to really give back to the environment, the ecology and the community as much as possible. That is the broad objective, and at the same time to keep work really contextual.

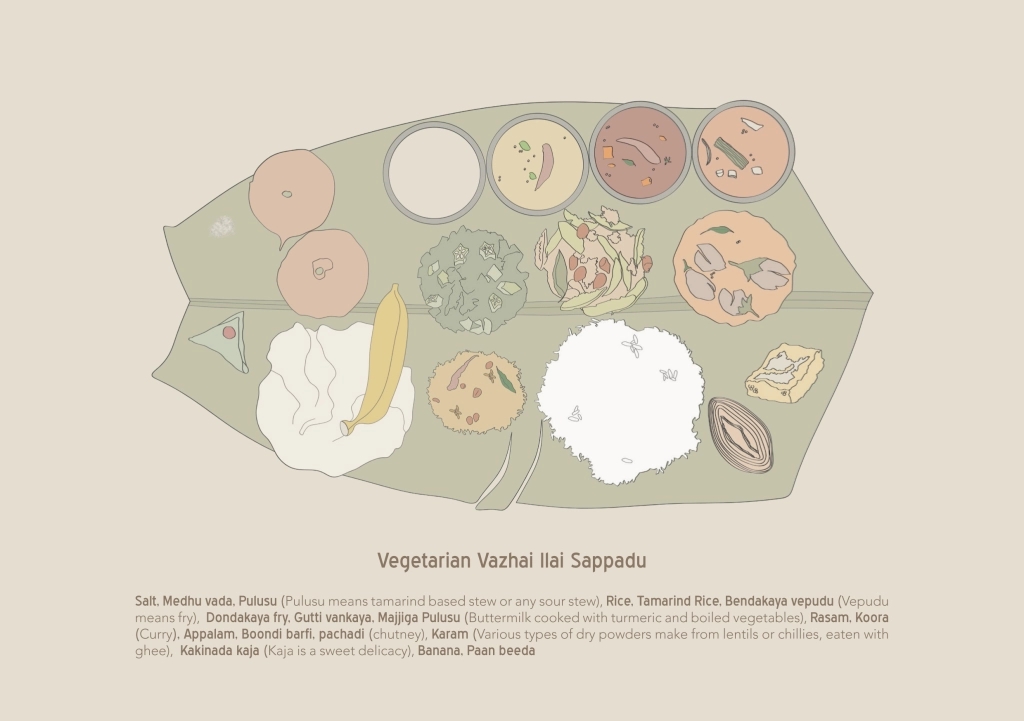

Scale is never an issue; even the smallest of scales, even the tightest of budgets interests us. Hence, the project selection has always been everything from institutional to looking at the public, and eventually wanting to do more public work, I always see private projects and gardens more as a test bed to experiment with, to learn from, but the quest is always to reach and improve what is happening at a more public scale, […] and to really focus on landscapes through our own cultural lens, not really taking cues from the West and celebrating, whether its art, culture, or ecology through everything we do in the landscape. Celebrating plant palettes, and discovering these unique aspects of what we have.

<09:55>

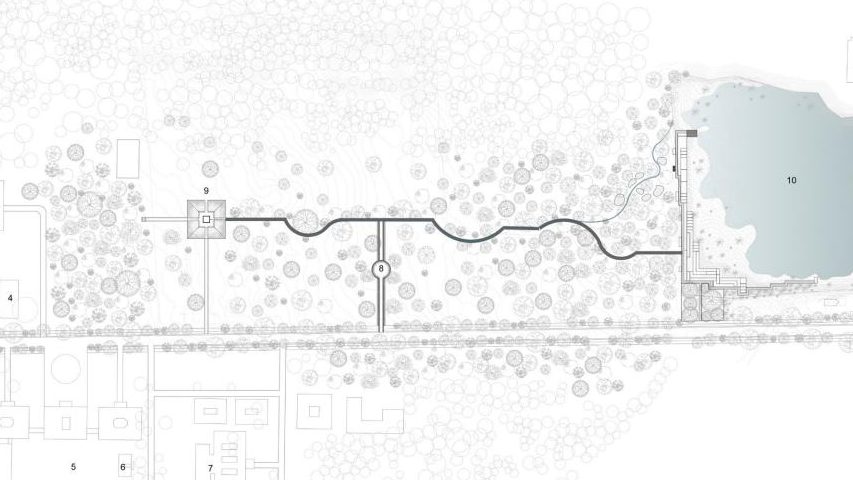

We try to do whatever we can to be involved in the public realm where we can address more people. For example, our project Bangalore International Centre (BIC) is a privately funded project but is completely open and free to the public. It is a democratic institution which encourages everybody to visit.

These are the landscapes that interest us the most and we would like everybody to be welcome in this space. Bangalore is a place with lots of open spaces luckily. We were involved in designing our own neighbourhood park – Namma Park, which was an initiative on our behalf along with the neighbours. As much as possible, we try to make projects for our own self when no public projects exist.

We have also been involved in Azim Premji Foundation Schools, efforts where the notion was reaching out to the community. It is not built but these are the projects that interest us more because we can engage with larger groups of people, and sometimes with really the disadvantaged.

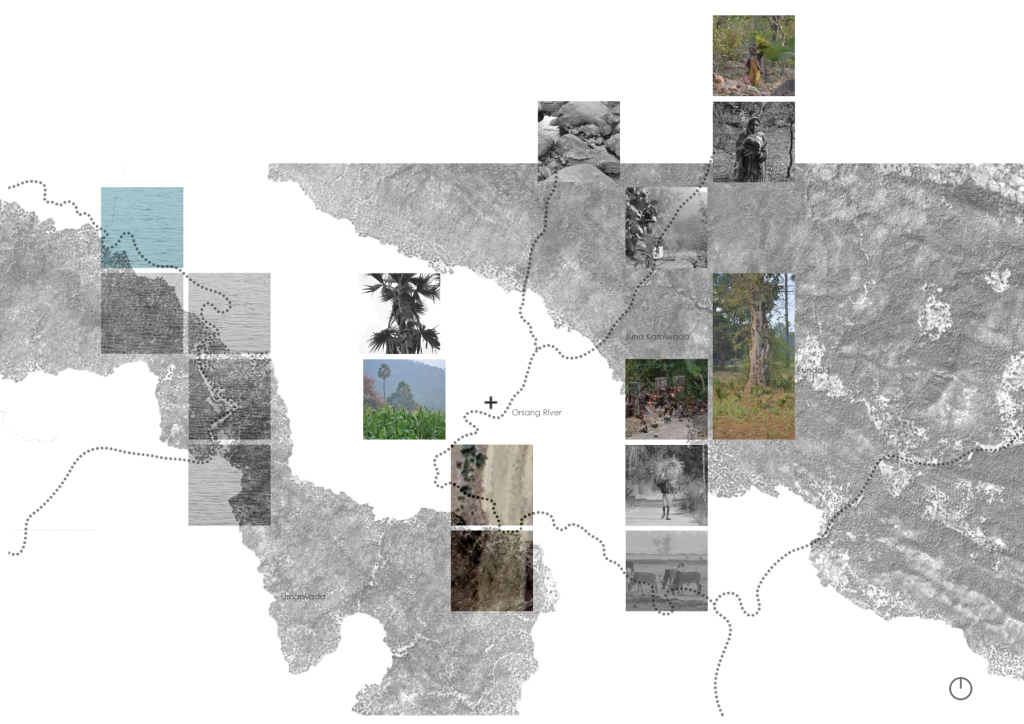

As a process, we go to the site, and we experience the site. Thereafter, there is a rigorous study that happens – mapping, and understanding the various layers that are involved in the formation of a site. For example, we are working on in Kathiwada in Madhya Pradesh. These are the sites that are not familiar to us, and the process involved conducting a series of GIS studies and also understanding site and terrain through the human perspective, through the indigenous people who lived there. Understanding the value systems, the rich tradition that they carry, which is more interaction with the environment, and knowledge of medicinal plants, I think one part of it is academic research – also understanding the systems that exist on site but also going beyond to understand people who inhabit and the other larger anthropomorphic extensions that exist.

I think the process is a combination of this and then the execution tends to be hands-on. We like to spend time on-site, and to be there to implement things that happen on-site.

<13:10>

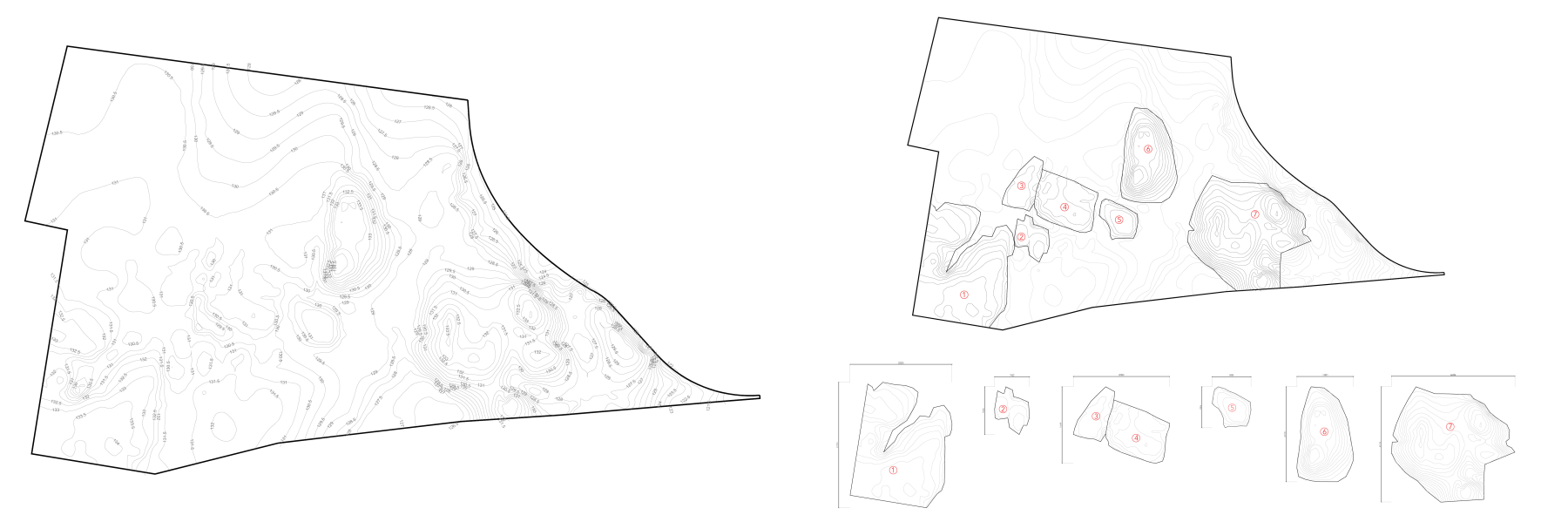

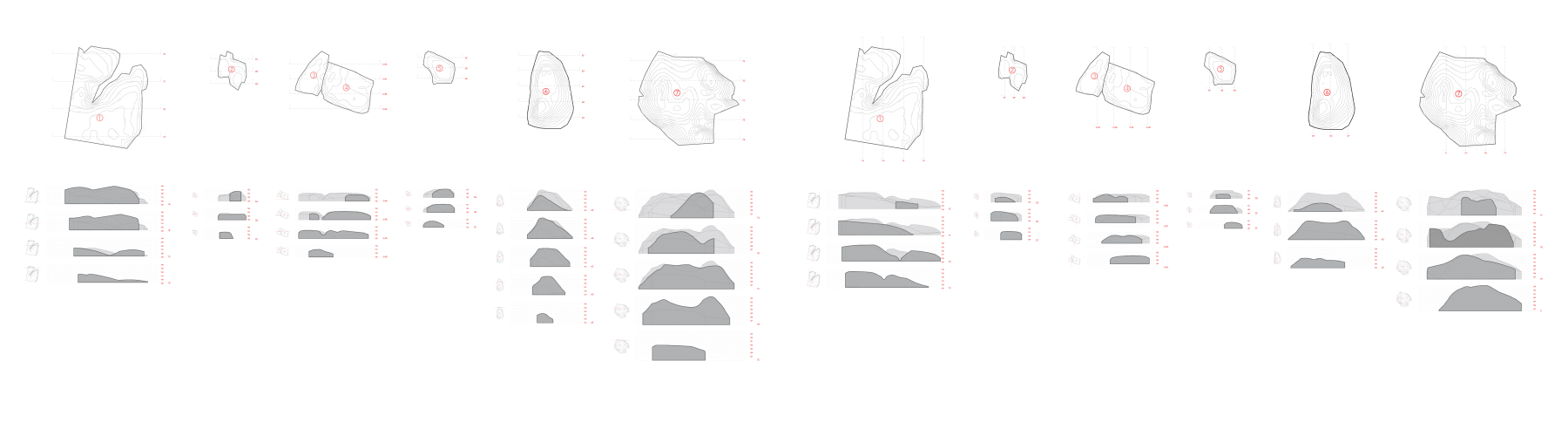

VS: The tools of representation are very different from architecture. One big tool is mapping. We tend to map the various layers that exist on-site, whether it is geology, the underlying systems such as water, vegetation – all of these comprise an effort of mapping and putting together our understanding of it, more in a scientific way and expressing it more in an artistic way as well, which perhaps also captures many senses, that are intuitive, also our emotional response to site.

I feel like this mapping exercise is a combination of this scientific meeting – the more emotional and the analytical coming together.

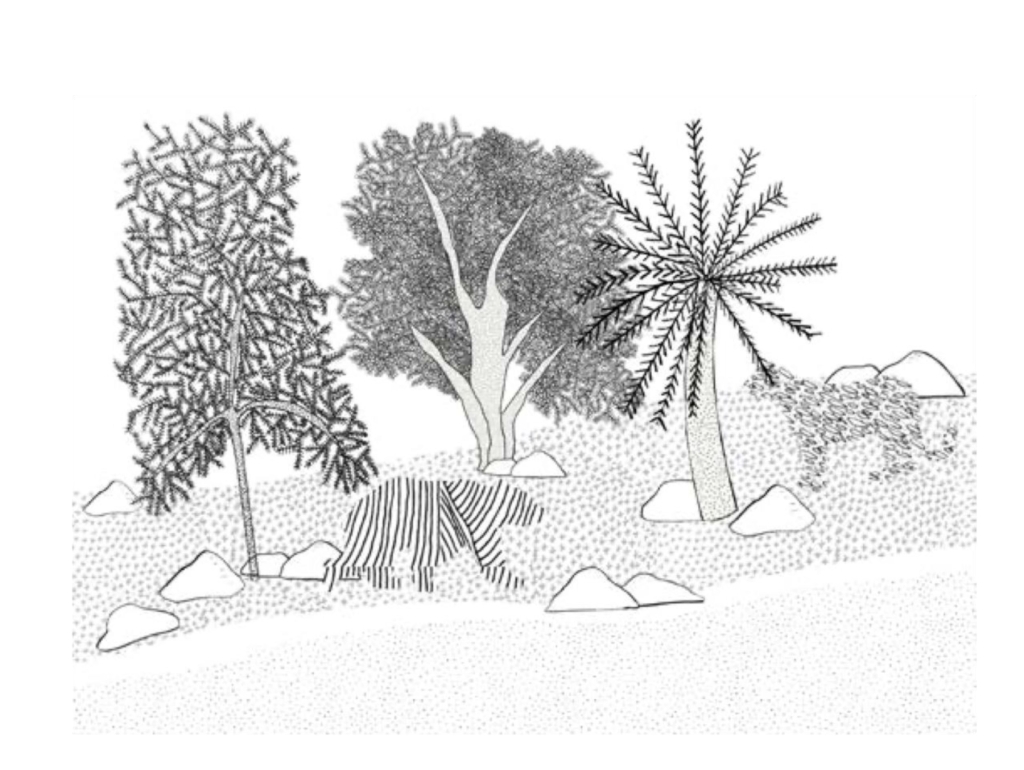

Apart from the tools of mapping, we look at 3D dimensions because that will also work with sites. We are working in Hyderabad on a site which is a boulder-scape. The question there was, how does one intervene in a way that is gentle, where it is almost an insertion, and almost highlighting all the voids on site? We also do intensive surveys of site vegetation, understanding, what grows on site, and becoming familiar with it.

The whole idea of communicating landscape which is sometimes very intangible is more about an experience rather than a 2D image. Communicating the whole landscape experience is challenging. We are also in the process of discovering what really works and moving away from 3D oriented ways of representing, away from depending on the architectural representational crutch.

We do a series of drawings for ourselves initially, to understand a site which could be in the form of maps, or analytical diagrams. We are not always hoping for the client to understand this. For clients, it is this, along with a set of images, that conveys the mood of the landscape. For examples, images that look at progressive time span, a larger evolution of the landscape. Now, it is moving more into film or representing it as moving images, as a means to represent landscape or soundscapes. Contextually, our cultural landscapes are experienced in many ways; whether it is the lighting of an agarbatti (incense sticks) on a daily basis, experiencing fire and light, or landscapes that include soundscapes.

For me, the quest has always been how do you represent these intangibles through drawings or visuals or other modes of communication. I literally feel that Indian landscapes cannot be experienced through the senses alone.

We were working with RMA architects for a memorial in Udayagiri, and it looks at a sacred landscape within the campus. Udayagiri is a hugely geological landscape, where Rama got the Sanjivani. We had these wetlands on site where the perception of it is not so much water and rocks but it is all these birds, these migrating birds alighting into the water. A lot of times it is about how can we capture these moments within the landscape, which is more temporal, and intangible. That quest is always there, to capture the other. I feel Indian landscape is truly experienced through the human consciousness; it goes beyond the sensorial. It has a certain degree of complexity. I try to derive inspiration from all of this but the quest to represent more in a landscape way still continues to be an ongoing journey for me.

VS: […] The measure of success of a project is being involved in the process after the process is so-called over because a landscape continues to evolve over a period of time. Maintaining the connections that I have with people, to ensure that I am a part of the landscape, personally, that is what is successful for me. However, for the success of a project, it is meeting the goals which we set out for the project but also looking at the goals where sometimes it is probably biodiversity.

For example, to increase biodiversity in the Bangalore International Centre project, it was about looking at increasing urban pollinators, as that leads to better food. This whole cycle, how even small microscopic spaces have the power to enrich this.

CONTEXT

<30:00>

VS: I have observed in the last ten years that there is definitely awareness about landscape. A lot of the clients have been fantastic in giving a lot of support and encouragement even from my first project, Neev Academy with Kavita Gupta Sabharwal being a really inspiring client to work with. I feel awareness about landscape has generally grown. However, an idea of landscape being something that goes beyond the aesthetic realm needs to catch up.

I think also different perspectives of what landscapes can be, and how different practices can address issues of landscapes and having this myriad ways of practice but also furthering questions of critical issues that exist currently – whether its limited resources, whether its climate change, whether its biodiversity fragmentation; how can landscape really look at addressing challenging issues that we have, but at the same time how can we stop using the West and the way the West positions itself in terms of practice being a crux for us to fall back on?

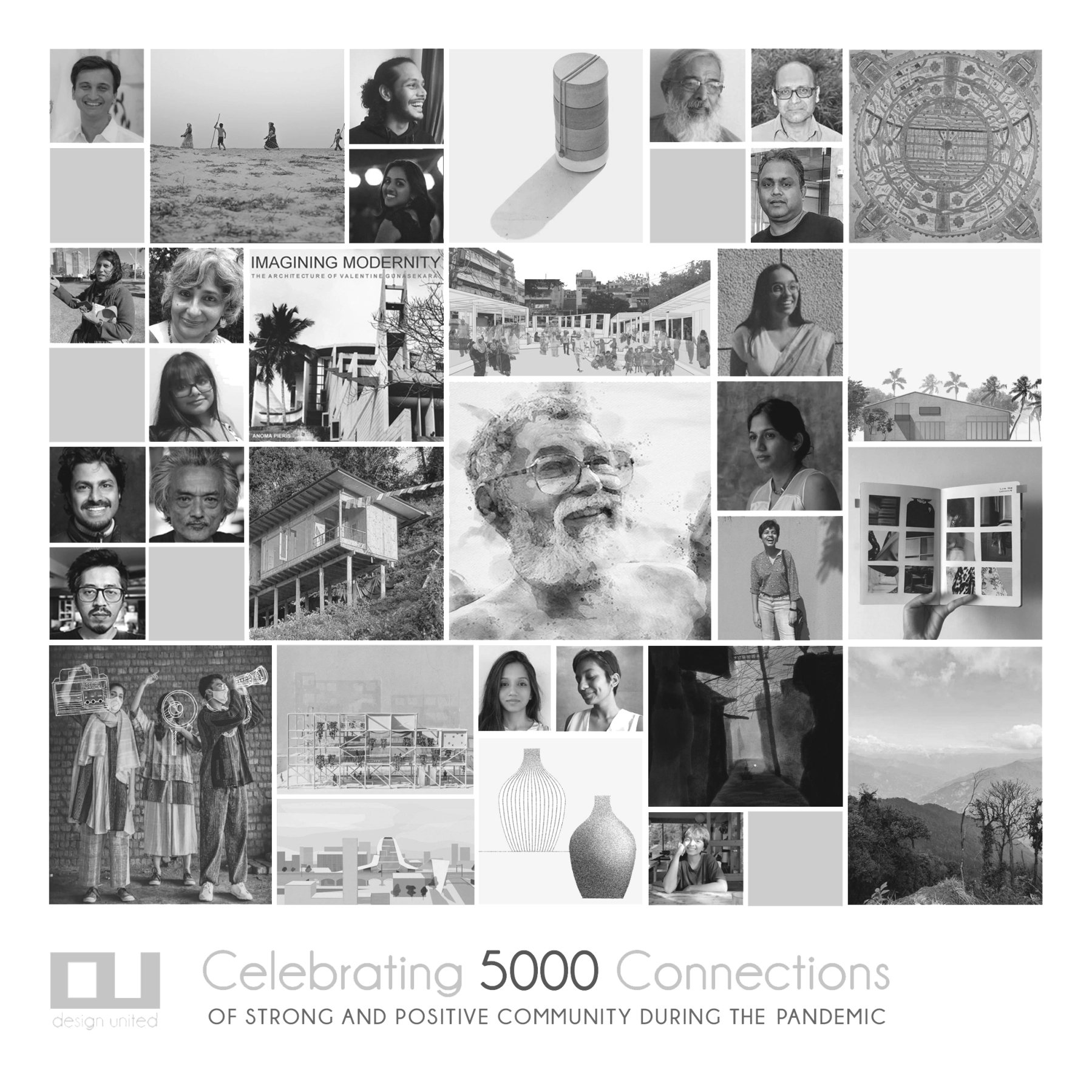

This whole idea of reference to what is familiar, great thoughts and talents from our region that we can interact with, a place to share process, a place to obtain mentorship was all of the things that I felt we lacked. Post academia, in the Indian context, I do not think we have any rigorous engagement with the profession which goes beyond looking at a certain amount of lectures. Whether it is continued education, whether it is looking critically at practices, even coming together as friends observing beyond a certain amount of ideas, whether we can delve deep and give one another critical opinions, I think these were all missing. The idea of collaborating with talented people we can relate to – whether it is a graphic designer from Bangladesh, or an environmentalist from Sri Lanka – all seemed very appealing. That is how Design United started as a place to share, collaborate and come together.

Design United is something that I am very involved in, and for me personally, it has been very enriching to meet with new people and it has informed my practice as well. This whole language of multi-disciplinary connections and collaborations and really looking at practice in a critical way which reaches many people, that is very necessary. We cannot always look to the West to give us examples. We have great examples, not just culturally but even practitioners whom we may not know about. One more thing about Design United is reaching out to people who build and create, and even patronage. Can interested real estate developers who feel this sensibility be a part of this conversation? Can patronage fuel creative ideas? These are some of the questions I am grappling with but it is also an outcome of what I constantly think of in a practice.

Drawings and Images: Courtesy VSLA

Filming: Vcams, Bengaluru

Editing: Gasper D’souza, White Brick Post Studio

Praxis is editorially positioned as a survey of contemporary practices in India, with a particular emphasis on the principles of practice, the structure of its processes, and the challenges it is rooted in. The focus is on firms whose span of work has committed to advancing specific alignments and has matured, over the course of the last decade. Through discussions on the different trajectories that the featured practices have adopted, the intent is to foreground a larger conversation on how the model of a studio is evolving in the context of India. It aims to unpack the contents, systems that organise the thinking in a practice.

The third phase of the PRAXIS initiative extends the continued effort in an ongoing series curated by Matter in partnership with Şişecam Flat Glass. Praxis 3.0 focuses on experimental vectors of practice and explorative models that support thought-provoking ideas and architectural processes.

Praxis is an editorial project by Matter in partnership with Şişecam Flat Glass.