Two Pioneers of Modernism in Ceylon

By David Robson

David Robson pens an empathetic memoir outlining the life and works of Sri Lanka’s two pioneering architects – a man by the name of Andrew Boyd and a lady by the name Minnette de Silva – in an attempt to restore their well-deserved place in the history of Modern Architecture from Sri Lanka and to bring into light their exceptional merit.

Andrew Boyd

Born in Cornwall in 1905, Andrew Boyd was the son of an Indian Circuit Judge and experienced a typically dislocated Raj childhood, spending part of his childhood in India and part of it at school in England. His father encouraged him to join the tea business, and in 1927 arranged for him to become a tea taster with Liptons in Ceylon. There he was befriended by the photographer, Lionel Wendt, and moved in a circle which included the painter George Keyt and the poet/diplomat Pablo Neruda. Wendt kindled Boyd’s interest in photography and this in turn led him to architecture.

Early in the 1930s, he returned to London and embarked on architectural studies, first at the Northern Polytechnic and then at the Architectural Association in Bedford Square. After qualifying in 1937, he spent two short years in Ceylon and renewed his friendship with Wendt and Keyt. Wendt encouraged him produce a photographic study of traditional architecture and this was published in the Observer Annual of 1939 alongside an article which praised the simplicity and honesty of village houses.[1]

In 1938, George Keyt was commissioned to produce murals for the Gothami Temple in Borella by Mrs. Charles Pieris, a wealthy benefactor and patron of the arts. Boyd designed a studio for the artist in the temple precincts and remodelled the temple image house to create a top-lit ambulatory.

This led to a commission from Mrs. Pieris to design two projects on her land in Colombo Colpetty: a single house in 5th Lane and a semi-detached pair of houses in Alfred House Gardens. These were quite unlike anything seen before in Ceylon: compact functionalist houses that offered practical efficiency combined with sun shading and cross-ventilation. The twin houses had continuous balconies at first floor level and employed an asymmetric roof with a clerestory ventilator. The single house incorporated a second floor terrace under a cantilevered sun-breaker.[2]

Mrs. Pieris’s son Harold then commissioned Boyd to design a villa on the hillside above the Kandy Lake for himself and his wife Leah. With its sensuously curving façade, this stood out like a beacon of modernism and earned the nickname ‘the ship’. The lower floor consisted of a long open loggia which led to the main entrance and staircase. On the first floor the sitting room and main bedrooms opened to generous balconies which looked out across the town, and were protected by cantilevered sun-breakers.[3]

During the course of the project, Boyd had an affair with Leah Pieris, and when he returned to Britain after the outbreak of the War she followed him and became his wife. This all passed off amicably, it seems, and Harold Pieris married Peggy Keyt, George’s sister. But neither Boyd nor his wife ever returned to Ceylon.

These three houses were the first examples of ‘modern architecture’ to appear in Ceylon, though their impact was muted by the outbreak of war. The Kandy house was not completed until 1943, and photographs that Wendt sent to England were lost at sea, so that Boyd did not see the finished house until much later.

After the War, Boyd joined the London County Council Architects’ Department where he worked from 1949 until his death in 1962. Here he was credited with the design of an important comprehensive school at Eltham Green in 1952 as well as a number of housing schemes in southeast London.

Boyd was a committed communist and was one of the founder members of the Britain China Friendship Association. He became a friend and collaborator of Joseph Needham, the author of the monumental work ‘Science and Civilization in China’ and in 1962, the year of his death, published his own seminal book ‘Chinese Architecture and Town Planning’.[4]

Andrew Boyd lived a number of seemingly separate lives – a tea taster, an accomplished photographer, an innovative architect in colonial Sri Lanka, a successful local authority architect in post-war London and a Chinese scholar of distinction. He deserves to be remembered as Sri Lanka’s first modernist architect.

Minnette de Silva

If Boyd was the last architect of Colonial Ceylon and its only modernist, Minnette de Silva was the first modern architect of Independent Ceylon. She was born in Kandy in 1918, and died there in 1998. Her final act was to publish the first volume of her autobiography, though sadly, when it did finally appear, it was under-edited, incomplete and failed to do her justice.[5]

Minnette was the fourth of five surviving children of George E. de Silva, a Sinhalese lawyer and founder member of the Ceylon National Congress, and his Burgher wife Agnes Nell. De Silva was one of the first Sinhalese lawyers to break into a profession hitherto dominated by Burghers. He became an important member of the Legislative Council during the years before independence and, with his wife, campaigned successfully for universal suffrage and votes for women. Following accusations of corruption, he lost his seat in 1948 and died in 1950.

The family lived at St. George’s, a house at Katukelle on the outskirts of Kandy built by Minnette’s mother to a design based on her own parent’s house at Diyagama. Here they entertained a string of international figures including the Nehrus. But Agnes was not the only woman in the family to design a house – Esmé de Silva, the wife of Minnette’s elder brother Frederick, had studied at the Slade in London and had visited the Bauhaus. In the late 1930s she also designed her own house – the house which is now the hotel known as Helga’s Folly.

Minnette had an unconventional childhood and somehow arrived at the idea that she wanted to become an architect, unprecedented for a woman of her background. Having worked briefly for a Parsee architect called Billimoria in Colombo, she persuaded her parents to allow her to enrol in a private school of architecture in Bombay.

After studying there intermittently for three years, she worked for a time in Bangalore on the masterplan for Tatanagar under Otto Koenigsberger, a refugee from Nazi Germany who was the Mysore State Architect and who would later succeed Maxwell Fry as Head of the AA Tropical School in London. Back in Bombay, she and her elder sister Anil were founder members of MARG (the Modern Architecture Research Group) and together with Mulk Raj Anand, they started a journal of the same name devoted to the Arts and Architecture, though Minnette left for Britain at the end of 1945 before the first issue appeared.

There is no hard evidence to link Minnette de Silva with Andrew Boyd. However, both served as advisory editors during the first five years of MARG’s existence and both contributed articles. It is also noteworthy that both were friends of George Keyt, and that Boyd’s Pieris House in Kandy was next door to Minnette’s brother’s house. One suspects that they would have known each other, and that Minnette must have been inspired both by Boyd’s publications and by his three houses, though she would later deny this vehemently.[6]

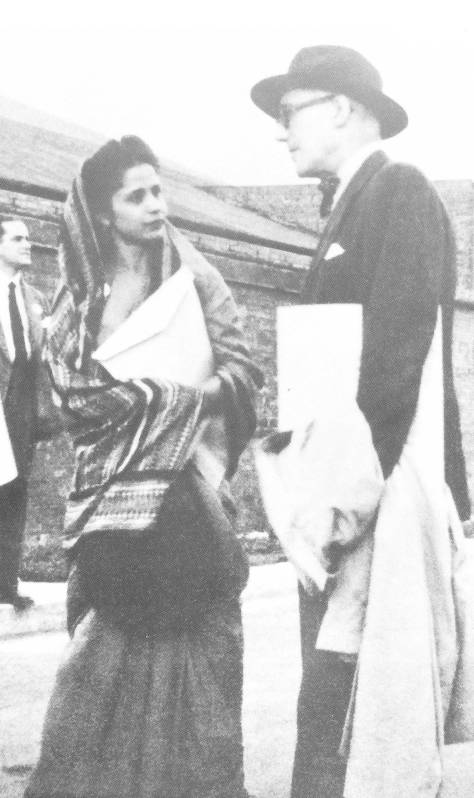

Minnette came to Britain in 1946 to complete her studies at the Architectural Association and lived in an attic flat in Saville Row. With her bright ‘saris’ and garlands of fresh flowers she stood out in the grey grime of post-war London. She was a skilled networker who got herself introductions to the great and the good and mixed with the leading artists and architects of the day. In Paris, she met le Corbusier and they became close friends and corresponded regularly until his death. Although le Corbusier’s main biographer, Nicholas Fox Weber, catalogues many of his affairs, he makes no mention of Minnette. Charles Jencks, however, suggests that they were lovers and Minnette herself implied as much in later life.[7]

The first post-war C.I.A.M. conference was held at Bridgewater in 1947 and Minnette attended as the self-appointed delegate of Ceylon. Typically she sat herself in poll position in the group photograph between van Esteren and Gropius; le Corbusier was seated on the extreme left.

After qualifying in 1948 and becoming the first Asian woman to register with the RIBA, she was summoned back to her native Kandy by her parents, where she established an office in her family home, and remained, on and off, for the rest of her life.

1948-51 The Karunaratne House, Kandy

Minnette’s first commission was a house for a downward sloping site on the hillside above the Kandy Lake. Her clients were a conservative Buddhist couple called Karunaratne who were friends of her parents. At first sight it looked quite ordinary, resembling what was known at the time as an ‘American Bungalow’. However, its significance lay in the way that it is configured in relation to the sloping site and in its complex internal spatial organisation. The bedrooms were placed on the first floor beside the entrance and the main living spaces were relegated to the lower floor and opened to the garden. The staircase acted as the hub and linked a sequence of rooms at different levels.

Her aim was to build a contemporary functional home, but she also wanted to create the sort of interlocking spaces which would accommodate large family gatherings and traditional Buddhist ceremonies. She used modern construction – concrete columns, trussed rafters, glass blocks – but she also employed rough-and-ready local materials – rubble, brick, timber – incorporating local handicrafts – lacquer work, Dumbara weaving, terracotta tiles – and the work of local artists like her friend George Keyt who supplied a large mural above the staircase.

During construction Minnette had to contend with the scepticism of her clients and the jibes of fellow Kandyans, but when it was complete a local journalist described it as ‘ultra modern but not bereft of local flavour’. This landmark house is now a ruin and is scheduled to be demolished.

Writing – A Modern Regional Architecture

In 1953 Minnette wrote a prescient article about the Karunaratne House in MARG Magazine, describing it as an experiment in ‘Modern Regional Architecture in the Tropics’.[8] Her use of the term ‘Regionalism’ predated its use by international historians such as Frampton and Tzonis by a quarter of a century[9]. She was offering an alternative to the intellectual straightjacket of international modernism by demonstrating that a building could be modern and of its time and while responding to context and tradition.

Twelve years later, in 1965, she returned to this theme in a retrospective article in the Journal of Sri Lanka Institute of Architects which reviewed her work of the 1950s under the title: ‘Experiments in Modern Regional Architecture’.[10]

But she was a woman in a provincial backwater and nobody was listening.

The 1950s

Minnette was an inveterate traveller. In 1949 she attended the 7th C.I.A.M. Congress in Bergamo and in 1951 was involved in the preparations for Italy’s first post-war Triennale. In 1953 she attended the 9th C.I.A.M Congress in Aix-en-Provence where she again met up with le Corbusier who gave her a personal tour of the newly completed Unité in Marseilles. At all of these international gatherings she managed to pass herself off as the delegate from Ceylon, though she had no mandate so to do. In 1954 le Corbusier sent her a signed copy of his series of lithographs ‘The Poem of the Right Angle’ and she later visited him in Chandigarh.

Travelling was a time-consuming business and Minnette neglected her growing practice. She developed a reputation for unreliability and many clients were put off by her forthright manner and patrician bearing. A quote from artist Donald Friend’s diaries in 1957 is illuminating:

“Arthur (van Langenburg) waxed entertainingly on the subject of Minnette de Silva who, instead of superintending the construction of a house, went off to Europe, and is just returned, full of rage that the owners (who are stubborn but terrified of her) insist on Bevis Bawa planning their garden.”[11]

Ceylon became a popular location for film-makers and Minnette entertained the succession of stars who passed through Kandy. In 1954, she befriended Laurence Olivier and his wife Vivien Leigh who was filming ‘Elephant Walk’ on a tea estate above Kandy, and in 1957 she had an affair with David Lean, the director of ‘Bridge Over the River Kwai’ which was filmed at Kitulgala.

Minnette ran her office from the family home in Kandy. Her staff seldom exceeded six in number and she employed locally trained technicians. In 1956, she was joined by a young architect from England called Michael Blee. He worked with her on the Watapulu housing project and developed an ambitious system of modular house plans, though Minnette rejected these as being too complex and inflexible.

In the following year Blee was replaced by a young Danish architect called Ulrik Plesner. Plesner worked with her throughout 1958 until, growing bored with provincial life and resentful of the fact that Minnette failed to pay him a regular wage, he accepted an invitation to work with Geoffrey Bawa in Colombo. Plesner has written of the experience in his bizarre autobiographical fantasy ‘In Situ’ [12] in which his description of his arrival in Kandy and his seduction by Minnette reads like a Mills and Boon novel. He hailed her as a reformer but claimed that she lacked the ‘charm necessary to enthuse and inspire others with her vision’. In a newspaper interview he reportedly said of her: “She thought architecture morning, noon and night. She was always hard up, always struggling, but she was a genuine reformer, very bold, very clear in her ideas. Technically though she didn’t have a clue”[13]

It is clear that Plesner learned a great deal during his year with Minnette and what he learned he took with him to Colombo. He and Bawa struggled initially to adapt the principles of Tropical Modernism to Ceylon and her articulation of a Regional Modernism helped them to resolve their dilemmas. Bawa was much influenced both by her buildings and her writings – indeed it is unlikely that he would have made the leap from Tropical Modernism to Regionalism if she had not shown the way.

Unbuilt Projects

Minnette received a number of commissions for public buildings during the early 1950s, though none came to fruition. These included a school in Gampaha, a Red Cross hall in Kandy and a day nursery.

Her design for the Red Cross proposed a curving lightweight roof on steel lattice trusses. When the clients indicated that they would prefer a traditional Kandyan tiled roof she wrote an indignant letter and resigned from the job. Years later, in her autobiography, she admitted this reaction had been immature. Her autobiography is dotted with rueful accounts of abandoned projects and houses that were never built.

1952 The Daswani Houses, Pichaud Gardens, Kandy

The two Daswani houses were built on an upward sloping site on the outskirts of Kandy. They were intended for rental and were relatively small, offering less scope for spatial gymnastics than the Karunaratne House. Approached from below, the main accommodation was raised up above a carport and entrance loggia. The houses survive but are much altered.

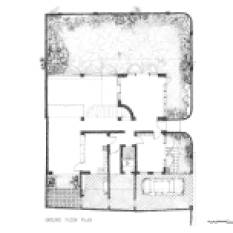

1952 The First Pieris House, Alfred House Gardens, Colombo

Minnette’s house for Ian Pieris in Colombo’s Alfred House Gardens of 1952 can be thought of as a prototype for contemporary living in a tropical city. The house is raised off the ground on columns and the groundfloor is given over to a carport, a guest room, two open loggias and a central midula or courtyard. The main living spaces are on the first floor where they enjoy enhanced privacy and better ventilation. Perforated grilles and glass louvers ensure constantly changing patterns of light and constant through breezes. The design may have been inspired in equal measure by the piloti houses of le Corbusier and the traditional tampita vihare or raised temples of medieval Sri Lanka, but, typically, Minnette merges these two ideas to make something which is uniquely her own.

Modern construction is used – insitu concrete slabs with concealed beams – in conjunction with local materials such as kabook (laterite) and rough stone. Traditional handicrafts are also in evidence – lacquered wood, decorative wrought iron grills and woven mats.

The house still belongs to the Pieris family and is in reasonable condition.

1954 C.H. Fernando House, Hampden Place, Wellawatte

The Fernando House developed in tandem with the similar Wickremaratna House in Edward Lane (now demolished). It was planned as a simple cube and employed a variety of local materials – fair-faced brickwork, exposed stone, timber – in a tactile way. Room heights were varied and the staircase acted as the pivotal point in the plan to connect the various levels and served as a ventilation chimney.

In 2012, the house was still occupied by the original owner, Mrs. Estelle Fernando, and was very much in its original condition.

1954 Asoka Amarasinghe House I, 5th Lane, Colpetty, Colombo

The first Amerasinghe House was planned around a central court or midula and achieved a flow of space – and air – between interior and exterior. Solid walls were emphasised with the use of rough stone and kabook and the sliding glass screens were divided by a framework of coconut wood. The house was demolished in 2011.

1955 Aluwihare Sports Pavilion, Police Park, Kandy

This simple pavilion was named in honour of Richard Aluwihare, the former head of the Ceylon police force and father of the celebrated batik artist Ena de Silva. It consisted of a solid stone base containing changing rooms and supporting a view platform under an independent over-sailing roof. It was demolished in 2011.

1956-58 The Watapulu Housing Scheme, Kandy

In 1954, a group of wives of civil servants came together to form a housing cooperative and eventually acquired about thirty hectares of land on the outskirts of Kandy overlooking the Mahaweli River. They approached Minnette to draw up a master plan and to design prototype houses.

A project of this kind, involving more than two hundred participants, was new to Ceylon and was fraught with difficulties. Minnette was overwhelmed by its complexity and was not paid a fee which was commensurate with the work it involved. Visiting the site today it is apparent that, although her masterplan formed the basis for the layout, it was not followed in detail. A few of the two-hundred-and fifty houses still show signs of the hand of the architect but it is clear that many of the participants later extended and transformed the original designs and that many others had opted to design their own houses from the outset.

1957 The Senanayake Flats, Gregory’s Road, Colombo

In 1957, Minnette was commissioned to design an apartment building in Colombo’s Gregory’s Road. The development consisted of four blocks on three floors which together contained ten apartments and ten garages. The blocks were canted in plan so as to define two inner access courts and a central service court. Each apartment opened onto a generous balcony and was like a ‘bungalow in the air’. Here the language is more overtly modernist and the curving facade recalls Boyd’s house in Kandy. The flats survive and are still in fairly good condition.

This important design was unlike anything that had hitherto been built in Ceylon and ought to have served as a potent prototype for contemporary living in a tropical city. It followed the precepts of the Dwelling Manual that le Corbusier had set out in ‘Towards an Architecture’ and addressed such issues as land scarcity and the need for increased densities, changing family structures, the disappearance of live-in servants and the increasing mechanisation of household tasks. But it was largely ignored by Minnette’s contemporaries.

Hotels

Minnette was involved with the design of three hotels.

One, for a site on the beach at Kalkudah on the east coast, proposed chalets raised on stilts with cadjan (platted coconut) roofs and was inspired by the form of traditional brick kilns. The project was initiated in the late 1950s and Minnette continued to develop ideas for it over the next ten years, but it was never built.

Another design, following a similar philosophy, was for a hotel at Sigiriya. This again proposed chalets, built from traditional construction, and clustered around reception buildings in the manner of a traditional dry-zone village. Although it was built, it was not a commercial success and seems to have fallen quickly into ruin.

Both of these designs predated the eco hotels which would become popular some forty years later, revealing the extent to which Minnette was ahead of her time and underlining her failure to convince other people of the potential of her ideas.

In 1959, she modernised the old beachside rest-house at Hikkaduwa and added a new wing. Six years later, this was buried in a further round of alterations by Geoffrey Bawa. Later, the whole complex was demolished to make way for the Coral Gardens Hotel.

The 1960s

The 1950s had been Minnette’s busiest decade, but she lost her mother in 1962 and suffered subsequently from bouts of ill health and depression. She continued to travel throughout the 1960s, spending long periods abroad and allowing her practice to falter. Ironically, her career went into decline just as the architect Geoffrey Bawa was embarking on his.

1960-61 Nadesan Villa, 5 Hermitage Road, Kandy

Like the Karunaratne House, the Nadesan Villa was located on the hillside above the Kandy Lake. It was conceived as a long rectangular pavilion cranked at its centre against the hillside with two projecting rear wings which formed a courtyard. The living accommodation was located at first floor level to exploit the views towards the lake.

Minnette persuaded her client to allow her to experiment with concrete roofs. She argued that a shell roof would save on timber and would obviate the maintenance problems experience with a tiled roof. The roofs were cast as low concrete vaults which projected out as up-turned eaves. She had intended to cloak them in flat tiles, both to improve the appearance and to reduce solar gain, but this suggestion was rejected by the client.

The house is much altered and hard to recognise, but the concrete shell roofs survive intact after fifty years.

Two Forgotten Houses in Colombo’s Cinnamon Gardens

Two of the most ambitious of Minnette’s houses from this period no longer exist and are known only from confused descriptions in her autobiography.

The house for A.G. de Silva in Alexandra Place dates from around 1960. The main living accommodation was contained in a two story block which ran back at right angles to the street. Two one side a garage wing defined a service court, while on the other a garden pavilion defined a pool court. A dramatically curved staircase occupied the knuckle of the plan.

The design employed state-of-the art concrete construction using circular-fluted columns, flat soffits with concealed beams and a cantilevered insitu staircase. It also made extensive use of screen walls built with square cast blocks decorated with patterned reliefs and perforations. Similar blocks had been used by Frank Lloyd Wright in his Los Angeles houses, but Minnette’s designs, in another interesting fusion of sources, also referenced the carved reliefs found on columns in Kandyan temples.

The house for Dr. P.H. Amerasinghe, the third for a member of that family, was situated in a lane off Ward Place. Its open-planned living spaces flowed around a central midula or open-to-the-sky court and were filled with light and air. Floating concrete slabs were used to vary levels and modulate the height of rooms. Typically it included a ‘downstairs bedroom suite’ for an ageing relative and a first floor ‘family room’ at the head of the staircase.

1963 The Second Pieris House, Alfred House Gardens, Colombo

In 1963 Ian Pieris commissioned a second house on a plot which was tucked away between his first house and a house that had subsequently been designed by Ulrik Plesner in 1961 for his daughter Malkanthi. This second house takes the form of a long courtyard plan, more reminiscent of a traditional monks’ dormitory than of the manor house model that had been used by Geoffrey Bawa in his house for Ena de Silva of 1960.

The result is disappointing – the courtyard is too narrow, making the plan seem introspective and gloomy, and the detailing is crude. It suggests that Minnette had been deflected from her earlier trajectory, perhaps by Bawa’s rising star.

1970 The Coomaraswamy Twin Houses, Albert Crescent, Colombo

The Coomaraswamy Twin Houses in Albert Crescent were built in 1970 and seemed to herald a new chapter in Minnette’s work. In fact, however, they marked the end of her mainstream career. The design was one of Minnette’s most accomplished and was a successful fusion of Corbusian modernism with traditional Sinhalese vernacular.

Each house was on three storeys – a many living level, a bedroom level and an attic. The bedrooms were arranged in an ‘L’ around the triple height living space under a swooping tiled roof and were linked around the outside by a continuous balcony. The interiors remained cool throughout the year.

The author lived in one of the houses during 1980-1981 and Minnette invited herself to stay on more than one occasion. Geoffrey Bawa also dropped in occasionally for a drink, simply because he admired the house and enjoyed sitting in its cavernous living room.

The houses were built by Colombo Commercial Company and the engineer was Chelvadurai, father of the architect C. Anjalendran. They were demolished in the mid-1990s. The architect Channa Daswatte bought the timber and used it in the construction of his own house.

The Seniveratne House, built in Kandy in the following year, incorporated similar features but was less coherent. It survives in a much altered state.

The Seventies – London and Hong Kong

Like many others of her outlook Minnette felt uncomfortable with the Bandaranaike government and in 1973, having closed her office, she moved to London and rented a flat from Maxwell Fry and Jane Drew[14] in Baker Street. Anjalendran, who was a student at the time, remembers helping her put together material for an article on Asian architecture for a UNESCO publication called ‘Courier’, but there is no record of it ever having been published. Here she wrote the South Asian section of a new edition of Bannister Fletcher’s History of Architecture and on its strength was appointed Lecturer in the History of Architecture in the University of Hong Kong.[15]

Minnette stayed in Hong Kong for four years from 1975 to 1979 and pioneered a new way of teaching the History of Architecture in an Asian context. During this period she amassed a large collection of photographs of vernacular Asian architecture and curated an exhibition that was shown at the Commonwealth Institute in London. Plans to write a comprehensive history of Asian architecture for the Athlone Press came to nothing.

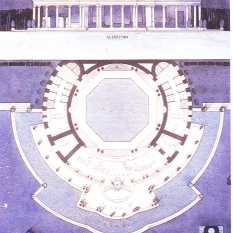

1982-84 Kandy Arts Centre

Returning to Kandy in 1979, Minnette, tried to revive her now moribund practice, but had difficulty in recruiting experienced staff. In 1982 she was commissioned to design a performance centre for the Kandy Arts Association on a site near the Temple of the Tooth that overlooked the Kandy Lake. It was to be used for cultural shows and conferences and would house a main performance space as well as exhibition spaces. The brief requirements changed as the project progressed and Minnette was required to enlarge the hall and add in extra workshops and studios, so that the final result lacked cohesion. The roof was supported on heavy timber trusses but it collapsed under its own weight as the project neared completion and had to be rebuilt to an improved design.

The theatre was conceived as if it were a natural amphitheatre in a village setting and was protected by over-sailing roofs which were designed to let in light and encourage ventilation. Unfortunately, the clerestory openings allowed rain intrusion and were later blocked in, leaving the hall dark and stuffy. But the entrance space, a progression of courtyards and pavilions under traditional tiled roofs preceded by a thorana arch, still retains a sense of magic.

In this, her last major project, Minnette again demonstrated the power of her ideas and the originality of her thinking, but she was let down by her lack of technical knowledge.

Two Last Houses

Minnette continued to take an interest in the world of architecture and in 1987 attended the International Union of Architects that was held in Brighton. However, following the problematic completion of the Kandy Arts Association, Minnette ceased to have any semblance of an office. However, in the early 1990s she was approached separately by two clients who were still drawn by her reputation as a creative designer.

In 1990 she was asked by the artist Raja Segar to help him design his house in Jaela. As well as sketches she produced a small model but did not participate in the detailed design or construction. Segar gave her a painting in lieu of a fee. The House and model still exist.

Her very last commission, in 1991, was to design a house on a tight corner site in Bullers Lane for Susil Siriwardene, the son of her earlier client Ian Pieris. Her sketches were developed by architect Lochi Gunaratne who also supervised the construction.

Twilight Years

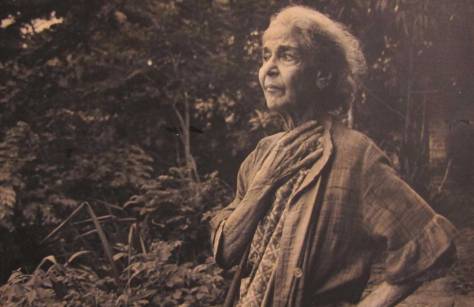

During the 1990s, Minnette had to contend with ill health and increasing frailty as well as loneliness and penury. She continued to work intermittently on her projected history of Asian architecture and embarked on her own autobiography, enlisting the help of a string of people.

The experiences of a young English woman called Kathy Stevenson who spent some time helping her to sort out her archives are recorded in a Guardian article of 2000[16]. “Minnette felt her life had been a huge battle, pushing people, trying to get things done. She knew she could be impossible. She had three-day temper tantrums and locked herself in her room when she didn’t get her own way.”

The architect Christopher Watson, winner of the 2013 Stirling Prize for Architecture, was one of two Cambridge students who were recruited to take photographs by Minnette’s sister Anil for a book that she was planning to write about Minnette’s career. The two spent about five weeks staying with St. George’s as Minnette’s guest and photographed buildings in Kandy and Colombo. Their film and contact sheets were left with Minnette and have since disappeared

In 1993, Dennis Sharpe, a writer and publisher with links to the Architectural Association in London, came out to work with Minnette on the text of the autobiography. He spent two weeks in Kandy with her but they soon fell out and he beat a hasty retreat.

Finally she received some support from her client Susil Siriwardene and from the architect Ashley de Vos who allowed her to use his office to assemble the material for the book.

At the end of 1998, Minnette suffered a fall which led to complications and she died, alone and forgotten, in a public ward of the Kandy hospital, a matter of weeks before the first volume of her autobiography appeared.

After Minnette’s death the house which had been her home throughout her life was abandoned, stripped of its contents, left to fall into ruin and finally demolished. What happened to her archives and to the material that she had gathered for her books remains a matter for conjecture, though the likelihood is that it was all destroyed.

Coda

The main phase of Minnette de Silva’s architectural career spanned a mere thirteen years from 1949, when she returned to Ceylon, until the death of her mother in 1962. After this she experienced a period of depression and ill-health during which her practice shrank before she finally quit Ceylon in 1973. Her success as a lecturer in Hong Kong during the late 1970s seemed to presage a second career as a teacher and academic. However, in 1980 she returned to Kandy where she spent the last two decades of her life, completing only three further buildings.

Although she produced innumerable designs and was brimming with ideas, her built portfolio remained quite small: around fifteen private houses, two apartment buildings, a cooperative housing development and two public buildings. Of these many have disappeared and only five remain in anything like their original state: the Pieris House I, the Fernando House, the Senanayake Flats, Pieris House II, and the Kandy Arts Centre.

Minnette was a woman operating in what was still a man’s profession within a chauvinist society, and she was stuck in a provincial backwater. The fact that she had to contend with so many problems forced her to develop a thick skin and contributed to her abrasiveness. Her patrician manner frightened off potential clients and she was bored by the nitty gritty of practice, paying insufficient attention to the detailed management of her projects. She was hampered by the fact that she had had very little hands-on experience at the beginning of her career and some of her projects were badly detailed and poorly executed.

Minnette may well have had more friends in India and Europe than in her native Ceylon. She worked very much in isolation and had few contacts with fellow professionals in Colombo. Astonishingly, inspite of her international reputation, she was never invited to teach in Colombo.

During the early part of her career she had strong ties with le Corbusier and Fry and Drew, but she navigated a course away from international modernism in order to develop a regional approach which would take into account tradition, climate, topology and local technologies. This led her to produce a handful of very significant ‘regionalist’ buildings during the 1950s and to write two important articles. In particular her article on the Karunaratne House of 1953 read like a manifesto for a ‘Modern Regional Architecture’ and was very influential.

The Sri Lanka Institute of Architects, which had largely ignored her during much of her career, finally awarded her its Gold Medal in 1996, two years before her death.

Minnette de Silva deserves recognition as an important pioneer of architecture in post-independence Sri Lanka. Most of her buildings have now been demolished or altered beyond recognition; hopefully those few that survive will now be conserved.

Bibliography

anon. ‘Minnette de Silva.’ Architecture + Design Vol XI, No. 4. Delhi: Jul-Aug 1994

Boyd, Andrew. ‘Houses by the Road’. Ceylon Observer Pictorial, Colombo: 1939.

Boyd, Andrew. ‘Houses at Colombo’. Architectural Review, Vol 88, London: July, 1940.

Boyd, Andrew. ‘A House in Kandy’. in Architectural Review, London: March 1947.

Andrew Boyd, Chinese Architecture and Town Planning, London: Tiranti, 1962.

Anjalendran, C. and Rajiv Wanasundera. ‘Trends and Traditions’. Architecture and Design, vol. 7, no. 2, Delhi: March-April 1990

de Silva, Minnette. ‘A House in Kandy’. Marg, vol vi, no. 3. Bombay: 1953.

de Silva, Minnette. ‘Experiments in Modern Regional Architecture in Ceylon’.

Journal of the Ceylon Institute of Architects, Colombo: 1965-66.

de Silva, Minnette. ‘Sri Lanka & etc’. Sir Bannister Fletcher’s ‘A History of Architecture’, 18th Edition, ed. by J.C. Palmes, London: Batsford, 1975.

de Silva, Minnette. ‘Kandy Art Association Cultural Centre’. Mimar 23, Singapore 1987.

De Silva, Minnette. ‘Minnette de Silva’. Architecture + Design, vol. xi, no. 4, Delhi: Jul/Aug 1994.

de Silva, Minnette. The Life and Work of an Asian Woman Architect.

Kandy: The de Silva Trust, 1998.

Dissanayake, Ellen. ‘Minnette de Silva: Pioneer of Modern Architecture in Sri Lanka’.

Orientations, Aug 1982

Fry, Maxwell and Jane Drew. Tropical Architecture in the Dry and Humid Zones.

London: Batsford, 1956.

Grover, Razier. ‘Minnette de SAilva – The Grand Dame of Sri Lankan Architecture’.

Architecture + Design, Delhi: Jul-Aug, 1994.

Hetherington, Paul. The Diaries of Donald Friend Vol 3.

Canberra: National Library of Australia, 2005.

Howell, Sarah. ‘Palace Revolution’. The Guardian, London: 1 May 2000.

Jencks, Charles. Le Corbusier and the Continual Revolution in Architecture.

London: Monacelli, 2000.

Lefaivre Liane and Alexander Tzonis. ‘Tropical Critical Regionalism’. Alexander Tzonis

ed., Tropical Architecture, Critical Regionalism in the Age of Globalisation,

Wiley Academy, 2001.

Plesner, Ulrik. In Situ. Copenhagen: Aristo, 2012.

Rankine, Esme. ‘Ceylon Woman Architect’. The Illustrated Weekly of India,

Delhi: 16 Jan. 1955.

Robson, David. Bawa: The Complete Works. London: Thames and Hudson, 2002.

Robson, David. Beyond Bawa. London: Thames and Hudson, 2007.

Sharpe, Dennis. ‘Minnette de Silva’ (obituary). Independent. London: 14 Dec. 1998

Footnotes:

[1] Andrew Boyd, ‘Houses by the Road’.

[2] Andrew Boyd, ‘Houses at Colombo’

[3] Andrew Boyd, ‘A House in Kandy’.

[4] Andrew Boyd, Chinese Architecture and Town Planning.

[5] Minnette de Silva, Life and Work of an Asian Woman Architect.

[6] Minnette de Silva in conversation with the author, 1980.

[7] Charles Jencks: ‘Le Corbusier and the Continual Revolution in Architecture’

[8] Minnette de Silva, ‘A House in Kandy’

[9] See for example: Liane Lefaivre and AlexanderTsonis, ‘Tropical Critical Regionalism’.

[10] Minnette de Silva, ‘Experiments in Modern Regional Architecture in Ceylon’.

[11] Paul Hethington, The Diaries of Donald Friend, Vol.3, p.409.

[12] Ulrik Plesner, In Situ

[13] ‘Palace Revolution’, Sarah Howell, Guardian, 1 May 2000

[14] Maxwell Fry and Jane Drew taught at the A.A. Tropical School and were authors of Tropical Architecture in the Dry and Humid Zones, (London: Batsford, 1956).

[15] Minnette de Silva, ‘Sri Lanka’ in Sir Bannister Fletcher’s History of Architecture.’

[16] ‘Palace Revolution’, Sarah Howell, Guardian, 1 May 2000

DAVID ROBSON

David Robson’s intriguing journey as an architect started in 1970s when he worked as the chief housing architect for Washington New Town. In the 1980s, he was assigned as an adviser to the committee formed by the Sri Lankan Government of its housing programmes and became intimate with the Sri Lankan landscape. In the early 1984, David Robson joined Brighton Polytechnic School of Architecture as a lecturer, where he worked till 2004.

Robson divides his time between practice and teaching and is a prolific writer. Robson has written some remarkable books on legendary Sri Lankan architect Geoffrey Bawa including ‘Geoffrey Bawa: The Complete Works’. Robson has also written and researched on contemporary practices of architecture in Sri Lanka and the Southeast with titles like ‘Anjalendran: Architect of Sri Lanka‘, and ‘Beyond Bawa: Modern Masterworks of Monsoon Asia‘.

The author wishes to record his thanks to C. Anjalendran who was the first to champion Andrew Boyd and who was a great support throughout this project and to Carolina Filippino who helped with the research into Andrew Boyd’s later life.

What a fascinating article. Thank you. I wonder if you might have any ideas about how to obtain a copy of her ‘The Life and work of an Asian Woman Architect’ today. It seems very scarce and I can’t really find a trace of it online. Perhaps there’s a stack sitting in a ware house somewhere in Colombo?

I’m also looking for a copy of the same book. Absolutely no trace of it online… Do let me know if you have any luck!