In the twentieth episode, Samira Rathod of Samira Rathod Design Atelier discusses the systems and ideologies of their Mumbai-based practice along with Jay Shah and a few of her colleagues. The conversation elaborates on the multi-faceted nature of their projects across architecture, interior, furniture design. The studio works in parallel with their workshop and research arm to operate across this array of disciplines. Their processes are guided by an ethos rooted in iterative explorations, meticulous detailing and an articulation of sensorial compositions. An editorial project by Matter in partnership with Şişecam Flat Glass, PRAXIS investigates the work and positions of diverse contemporary architecture practices in India.

EXCERPTS FROM THE INTERVIEW:

SR: Samira Rathod, Principal Architect

JS: Jay Shah, Associate Architect

FOUNDATIONS

<00:33>

SR: If I have to go back and understand why I did architecture, I would have to go back a few more years, and talk about how I had this wonderful art teacher under whose tutelage I used to spend every Sunday morning painting. I think that is where the seed of design or this love for composition began. I grew up thinking that I would pursue advertising, and be a graphic designer or a visual artist.

However, in those days, my parents were very keen that I take something that is more professional and accepted. It was either an option of being a lawyer, doctor, engineer, or architect. The reasons for joining architecture were purely that. Once I joined Sir J J College of Architecture, I almost felt like I was a misfit. I felt that my ideas were very different. The diligence to work was somehow mocked amongst the general attitude, and I found communication there very difficult.

Post that, I worked a little bit with Master and Associates, Uday Master, and that brought me back. In the fourth year, we had this wonderful faculty, Professor Chandavarkar and he started having conversations that engaged me and I felt a little more comfortable. I went to the US for a vacation, where I got a chance to work with somebody through Master and Associates in an office there and that is when I realised that I want to study. That is where the real engagement with architecture began.

From there I got my Master’s degree, and worked a little more, came back and worked with Ratan Batliboi, and with Rafi Azmi. That took about couple of years, and then post marriage, I went back to Ratan. I was working on a project there, but I did not finish the project because I got pregnant with my second child, and that is when I quit.

I decided to have an exhibition of furniture, because I did not have work. I had borrowed INR 5 lakhs from my father-in-law and put up an exhibition that landed the first project. Further on, we established a partnership firm at that point in time, which again dissipated. Around 2000, I partnered with Purvi Parikh opened Transforme Designs which was a furniture outlet. From there, we started my own firm, that is SRDA today, since 2000.

<04:50>

SR:

The core idea, that one started with, has not been diluted. It has been further and further reinforced. It is important that I distinguish between what a building is, and what we call architecture then.

Architecture is not a profession where you talk only about abstract ideas. At the end of the day, you have to build it and engage with all kinds of consultants. You have to engage with material, talk about costs, and there is this whole management, finance and the economics side of it which is absolutely real and physical. Then there is this sort of a metaphysical aspect of architecture, which is talking about enhancement of experience – where one is talking about if you can get the user of the spaces into another realm of thought. For a lot of people, these are two different things – however, for me that was always one. I never saw them differently.

<10:00>

SR: To support the studio, we had three verticals. I started SPADE, where a lot of ideation and experimentation happens, and we have a workshop where things are made. We make largely furniture but that is where I can take an idea and try it out, put it in the workshop, get people there and see what is the outcome. So, you have the ideation and then you have the making — that gives you a sense of a result. Thereafter, you take a decision and that informs the main studio, the main vertical — which is where the projects happen.

In terms of the research arm, I run it as something that does not always have to be connected to studio work but runs its own academic projects, academic ideas, and documentations. I think that for me is very crucial. I always believed that the research that you might undertake now will find its meaning, probably a decade later or even more. So, there is no immediacy in terms of result.

Probably ten years ago, we did a project through SPADE which is looking at the idea of dismantling versus demolition. As early as that we talked about how it is important to dismantle a building and recycle all its material, because we are really looking at depletion of resources and yet also talking about sustainability. That project that I talked about ten years ago, was a documentation of four buildings in Khetwadi, which were categorised as Heritage B buildings which were going to be demolished anyway. We made a little book, printed it out and documented it. So, we went in and only looked at an inventory of materials. I was not commenting on space or its beauty. I said we should just look at the quantum of materials.

One has to take every element for what it is, if it is broken while you demolish or dismantle it, then so be it, and use it again in that form. The whole point being that one minimises energy; even in compounding it into another material or even in retrieving it and then use that to create another building. We found that what was really needed in our studies was if I have to create a whole out of it again, then I have to find an intermediary that actually uses an adhesive to join it or a method that holds it again for the next twenty forty years. How do you give it a new life? That was the outcome.

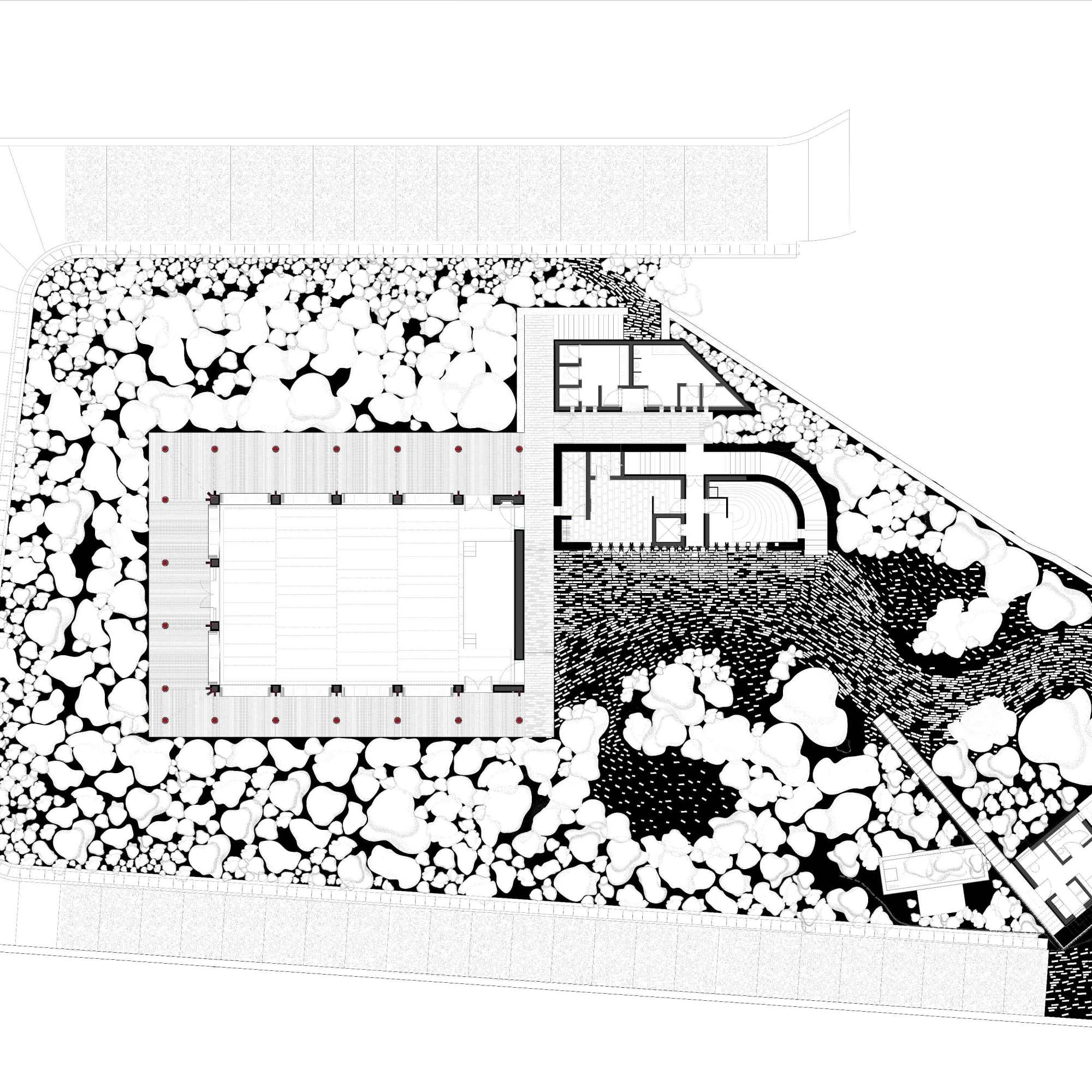

I am finding today that we were able to actually use that idea and really put it to absolute 100 percent practice in the pavilion that we created for Kochi. It is amazing because for ten years we had been talking about it and it was silent, and suddenly you get an opportunity where you can actually use it. We were able to use construction debris from buildings that were coming down just next door to the site in Kochi. It was amazing. It was great on energy, beautifully insulated thermally; we were able to bring down temperatures, we were able to actually not abuse the land. Especially, with the whole idea that if the structure is temporary, what happens to the footings? — We had no footings. It was a floating structure. So, when they dismantled it, they had the site back.

<14:46>

SR:

I think I am luckily supported by the office now of likeminded people. A lot of times, when you are over the hill, so to speak, and you have the younger lot that says “No, we do not want to go this way, because we believe in these ideas.” I think that is important.

CULTURE

<16:08>

JS: We are a very small tight knit team which really works well for us because the way that everything functions at SRDA is that we try to at least encourage a more collaborative process. What really happens at the studio is that there clearly is a directive that comes from Samira of course, and others, sometimes the client and then we leave it to the individual for a certain period of time for their own exploration. Hence, it is very individualistic in that manner in terms of the explorations and the directions or the opportunities that that one director has and once that progresses there is a culture of reviewing work every other week, or two-three days.

It is a very rigorous process and the culture is such that everybody works on everything. It is a very holistic way of looking at our practice instead of saying that an architect will only do architecture, and interior designer will only do that and you have to bring on another person to do some research.

PROCESS

<20:39>

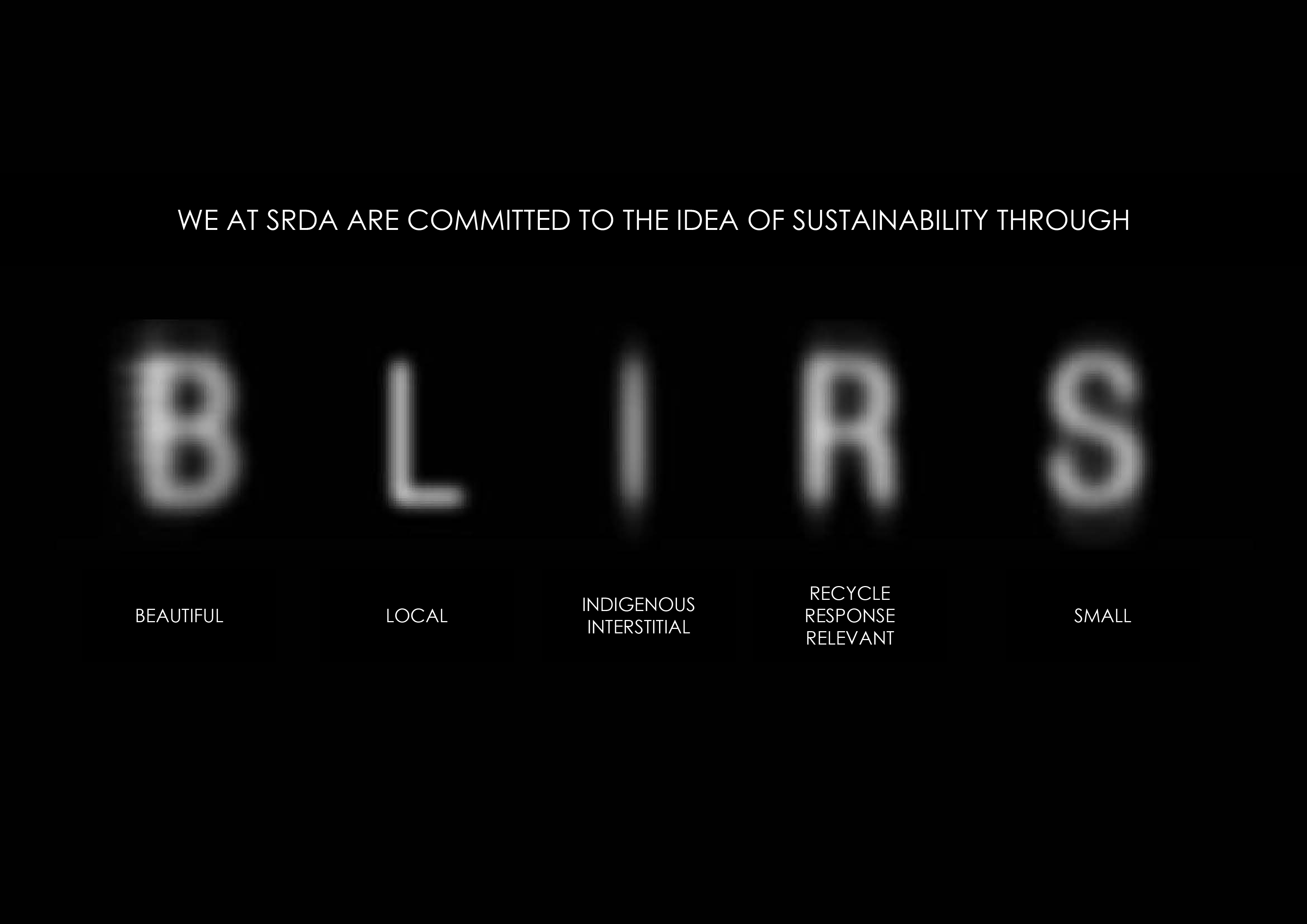

SR: Philosophically, we have an acronym which is called BLIRS. I think it is a lovely word […] the meaning of the word BLIR is when something is never discerned in its entirety, and there is this sense of ambiguity.

B stands for Beautiful, L stands for Local, I stands for Indigenous, R is Recycle, Relevant, Responsible, S is Small, Sustainable. Small comes back to looking at an object very closely, looking at a small details, and personally, I think of it as sustainability, about making things small, where you do not get into the bigness of things that you do not need, and where you are only feeding your ego. You do not really need that.

If you think of that metaphorically, it allows for many interpretations. There is ironically also a sense of completeness, because if you walk into our spaces, you will feel it does not need anything more.

<22:22>

SR: We started with architectural projects that were single residences, and then today we have a mixed palette of factories, big and medium scale schools, and even a skyscraper in Sri Lanka. The scale has really moved up and down.

The act of building is a performance that is outside of you, in a manner of speaking. Important to understand that there is a set of people available to you with a set of skills and you need to address your design for it to be executed by that set of skills.

If that equation goes wrong, is then where you will have trouble. I think in the smaller projects we were able to get that sense of detail that that we want to our satisfaction, but in the larger projects it is about allowing the team to work together.

<24:46>

JS: If I had to very simply put down what the process is like, I would say it is more visceral than pragmatic. Every project starts with an instinct — it is almost like it is an impulse which could be a natural reaction to say either the site, to the situation, or to the set of people you are dealing with, and then there is a development of that instinct.

<26:45>

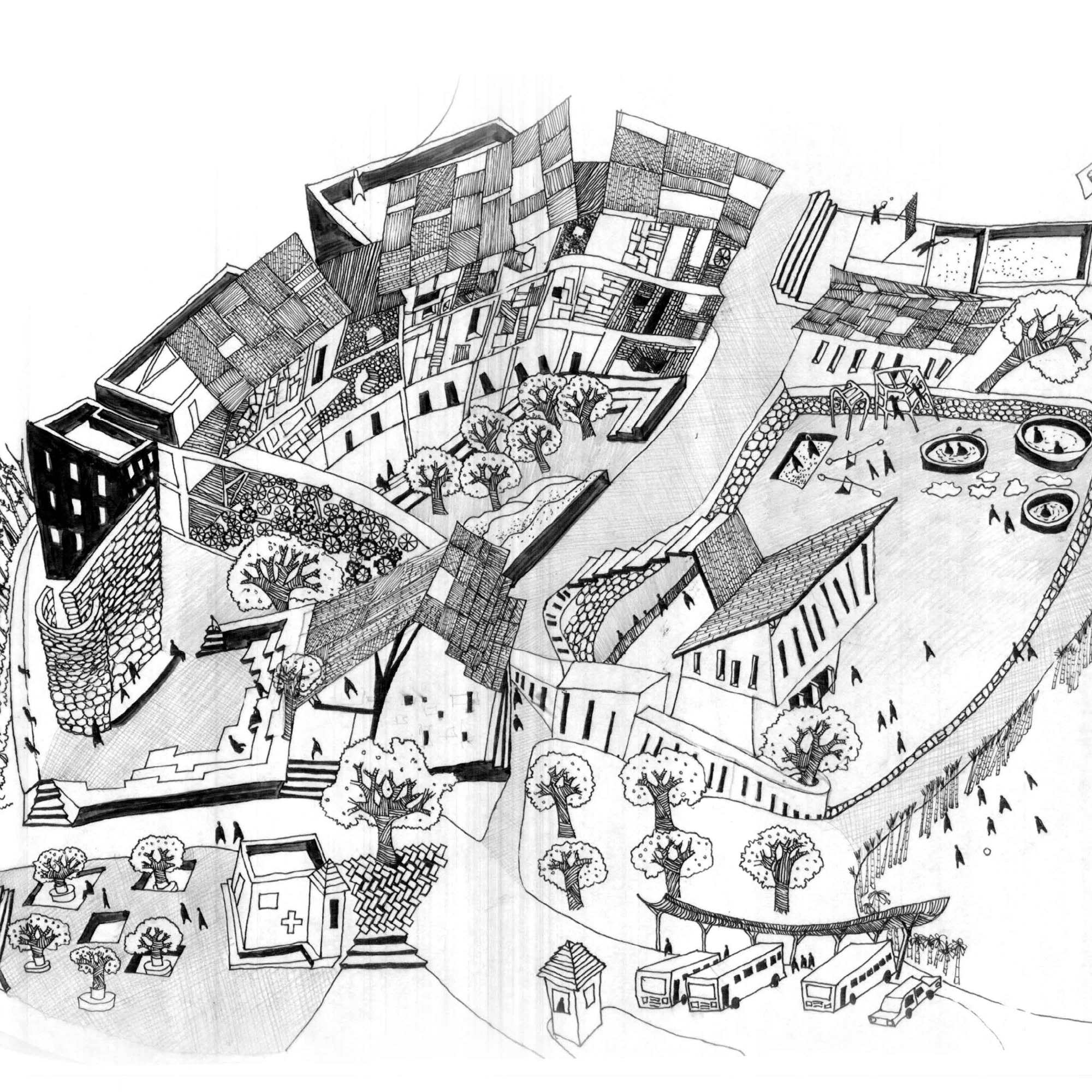

SR: The idea of drawing by the hand is very important. For me, your first sketches could be just responses, or questions, because you are not sure. You are sketching, and the questions therefore important to ask are, ‘Will this work?’. Before it becomes a design, it is tested through various layers.

<27:54>

JS:

I think the process of work in the studio is also not structured at many times. What that allows people who are involved with is that the particular process of designing a piece of architecture to do is to find their own joys within the process and the making of the architecture.

A door handle is never just a door handle for us, it is something that you are touching on a daily basis because of which there is a story attached to it and the way you touch it, the way your hand feels against it whether it is cold, it is warm […] It is a lot of these other ideas which are very sensorial in nature which one usually cuts out when the architecture has been made because then there is this question of a larger concept within that. There also is a question of how the body is with the space and how your touch and senses feel. The process is looking at also that level of detail.

<29:44>

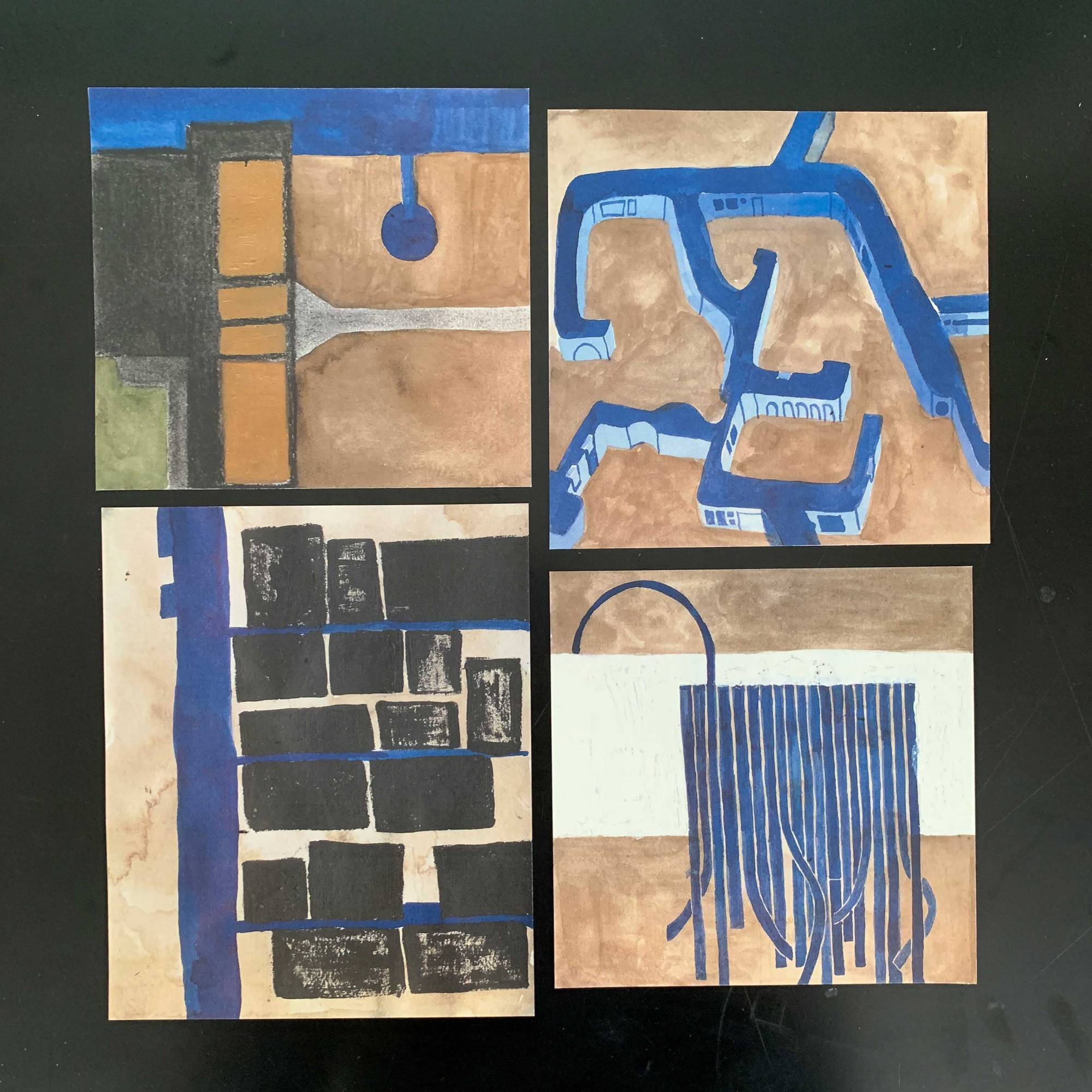

SR: I would like to think of the idea of making buildings as would an artist make their product. Also if that be the case then the idea of representation even in the earlier forms could be more than just a drawing. It could be dealt with in different medium. There was one project that we actually said we will not look at regular drawings and that to inspire and create more ideas or to see how we can explore this beyond the envelope of what is normally considered design. People in the studio were actually creating beautiful watercolour drawings that were actually stunning.

I think it is important to also have a great love for pencil drawings because lead allows expression, graphite allows expression — the line has power. For example, how powerful is your line, how broken is the line, how dark is the line, how dark is the shading, how you are expressing water — the sciography, the foreground, background all of that is expressed through these drawings. I think it is very important because one cannot do a discussion if the drawing that is shown to me does not have that seed of passion. The computer itself is extremely limiting especially, I do not think we are ready enough to know how to really use it, not for design at least. You cannot really relate to the discussion of architecture that is in your head. It is really myopic and I find that the exploration that has to go on by questioning in your head is limited.

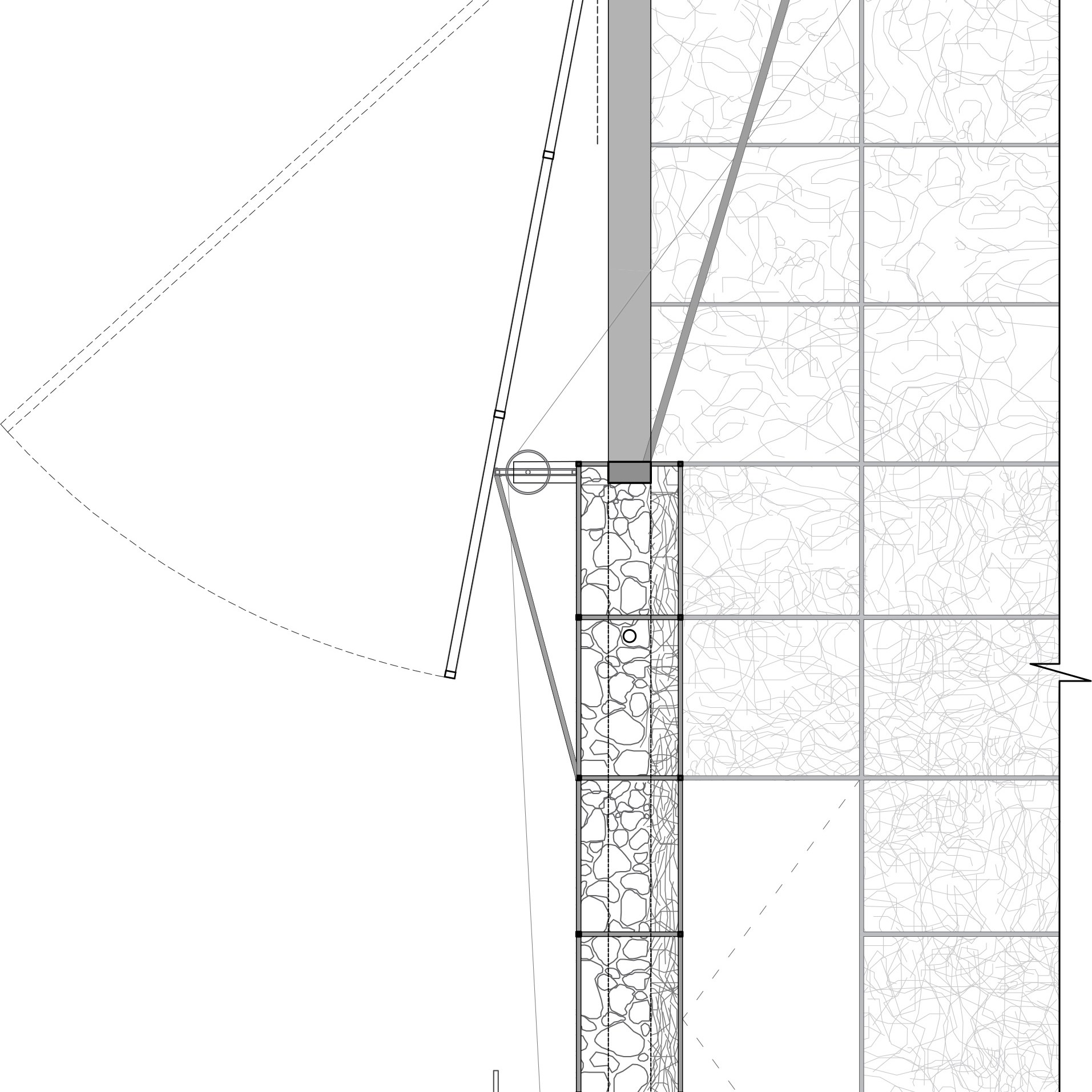

<32:50>

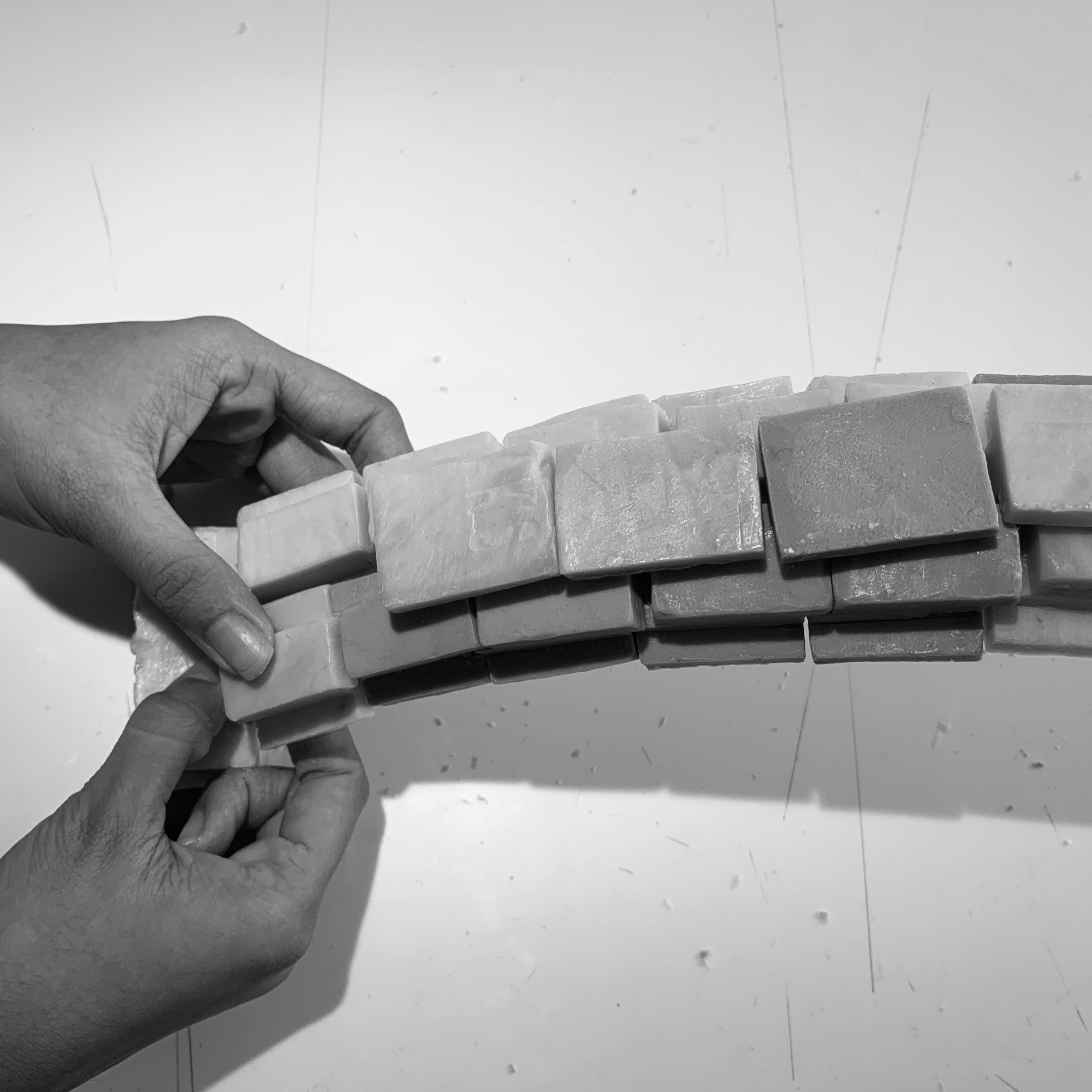

SR: We make models. At every change in design, there will be a model. I will not take a decision to say that this is good or bad or we go with it until it is made into a 3D model. You will see the models are really small because they can be made quickly and you can get a sense of scale and composition immediately so and then once things get more and more finalized and they get bigger, you see more detail in the model and the final model which is the model that is of the finished building is never made because that is the building. You would not see any well finished model in the studio because it is a study tool, it is not a presentation of the building yet. These are purely study models so they are either iterative or they are used just to understand wall sections or roofings or other details.

<39:20>

SR:

For me, a good building is not the one that just performs its function, it becomes architecture when you are able to take it to another level; when there is soul in it, when there is beauty in it, when there is poetry in it — that is when it becomes architecture.

<40:41>

SR: When I am teaching I am also therefore moving away from this treadmill and getting into a realm that is more metaphysical that allows a little more dreaming and there is this constant exchange of ideas which is learning and introspection during teaching. So, I think when you are teaching there is introspection because you are saying something and then you are asking that subconsciously to yourself “Is this for real? Is this what you did? Is this how you would do it? Is this right”; and the ideas then reflect in your work. If you are able to draw that back into the practice that is great.

CONTEXT

<42:05>

SR: In terms of systems we are very loose, in terms of efficacies, in terms of being able to stick to given formats, expectations, certain quality standards beyond which even an architectural firm cannot fall. In terms of strictures, there is no consequence, except maybe you lose a couple of projects and the practice falls eventually but as such there is no consequence. In that sense that is not good.

The other reason that is questionable or something that needs to change, I think is the policies around how our cities are built, how environments are looked after. I think we do not really have any solid policy other than the development rules. We need better policies definitely. We need better committees that address the idea of city planning, that address the idea of architecture in terms of permissions, how do you set up those things?

There has to be a policy on everything which is not written out in stone because times are changing too fast, and this has to be flexible and has to adopt and adapt. The policy has to be drawn so that it is constantly adapting and it has to make exceptions to the rules, to allow buildings or environments to be created which are not based on the rule book but which have its own new idea that it wants to talk about and that is what makes the city a thinktank. A city has to be a source of energy. You have to have these little gems of vivacity that there are in the city that allow you to say, “This is the fountain of knowledge, this is the fountain of thinking, this is where new things happen, this is where new idea stream from, this is where new energy comes from.”

What is great in India is the opportunity. You have a huge platform for opportunity, for experimenting, creating new ideas and that ironically is because there are not so many rules, so you can do many more things.

<46:06>

SR: On the whole, there is a huge shift from when there were just a few, handpicked people that one kept talking about as architects. Globally also, one only talked about a few architects such as Corbusier, Frank Lloyd Wright, Oscar Niemeyer and so on and so forth, but now it is not so easy to just take names because there are just so many. Hence, one will now talk of projects and I think that is great.

The conversation world over is about sustainability, so I think that is catching up and that is really good to hear in terms of how much of those sustainable ideas are becoming mainstream, that we do not know yet, that is the big question. The younger practices are thinking practices, resourceful and I think they are having a lot of fun so that is important too.

Drawings: Samira Rathod Design Atelier

Images: Photography by Samira Rathod Design Atelier or as attributed

Filming: Accord Equips

Editing: Gasper D’souza, White Brick Post Studio