An editorial project by Matter in partnership with Şişecam Flat Glass, PRAXIS investigates the work and positions of diverse contemporary architecture practices in India. The episode features Robert Verrijt and Shefali Balwani, the founding partners of the Mumbai- and Rotterdam-based practice, Architecture BRIO. Through strategic designs, their studio places experiential architecture as a background for the surrounding context. Outlined in this conversation is a glimpse into their process and the thinking behind the studio’s spatial, textured and meticulously detailed portfolio of work – furthering an understanding of facets such as materiality, technology, changing landscapes and the found terrain. The discussion also touches upon the executional, operational and economic workings of the practice in discussion with Rohit Mankar, Associate Partner, and Mimo Shirazi, Business Head at Architecture BRIO.

EXCERPTS FROM THE INTERVIEW:

RV: Robert Verrijt, Principal Architect

SB: Shefali Balwani , Principal Architect

RM: Rohit Mankar, Associate Partner

MS: Mimo Shirazi, Business Head

FOUNDATIONS

<00:45>

SB: Robert and I met in Technical University of Delft, in the year 2000. I was there on an exchange programme, and I studied in CEPT, Ahmedabad and at that time, Robert was looking to come to India on an exchange programme and our paths crossed. I think both of us experienced different kinds of culture shocks in each other’s context. When I was studying in CEPT, it was fairly dogmatic – the way we were taught architecture there. In a way, it was suggested that there is a right way and there was no broader array of approaches to architecture that we were exposed to or that we were taught. It was very strongly grounded in the modernist principles of architecture and, of course, with regionalism and context, climate and those principles informing how we design and looked at design.

Whereas in TU Delft, you were allowed to explore your own ways of architecture. There was no right or wrong, there were a multitude of possibilities and I think for me that was very difficult to grasp.

At the time, the Super Dutch movement was very dominant; there was a lot of thought to the concept and the purity of form and of architecture having a single architectural idea and how that converts directly into a building. For me, that was the biggest shift in thinking about architecture.

After graduating, Robert first moved to Sri Lanka to work in the office of Geoffrey Bawa, initially to work on retrospective exhibition on Bawa’s work; then later, joined the office of Channa Daswatte in Sri Lanka, and I joined Robert after graduating. In 2003, we were both in Sri Lanka working in Channa’s office and then in 2006, we started our own practice in Mumbai.

<03:47>

RV: In retrospect what I think one learns in TU Delft, Netherlands, from all this exposure that you got at the University of different schools of thought, is to really think flexibly in a way and think in an agile way of architecture. At the same time, what I felt was missing is the sense that architecture is more than just an idea, just a concept; its more than an idea literally being translated into a building and that there is a whole building culture that influences architecture, and this is something that I really discovered in India, studying there at CEPT.

What also fascinated me was the emphasis on observing culture, the way people live, how cities are working, and how that then influences architecture. Ahmedabad is also where I got exposed to the work of Geoffrey Bawa, an architect that was really not known in the Netherlands. But what really fascinated me there was, this sense of his work really deriving out of a sense of place.

I found an architecture that often was imagined to have disappeared in a landscape where the emphasis was not on the architecture itself but was on a much larger picture of what life is about. Architecture did play a role in that, but the landscape itself and the context and the climate played influence on the experience of the surroundings. Architecture either supported it or emphasised or heightened the experience of this environment. That is why the both of us moved to Sri Lanka to kind of relearn how this was done.

<10:50>

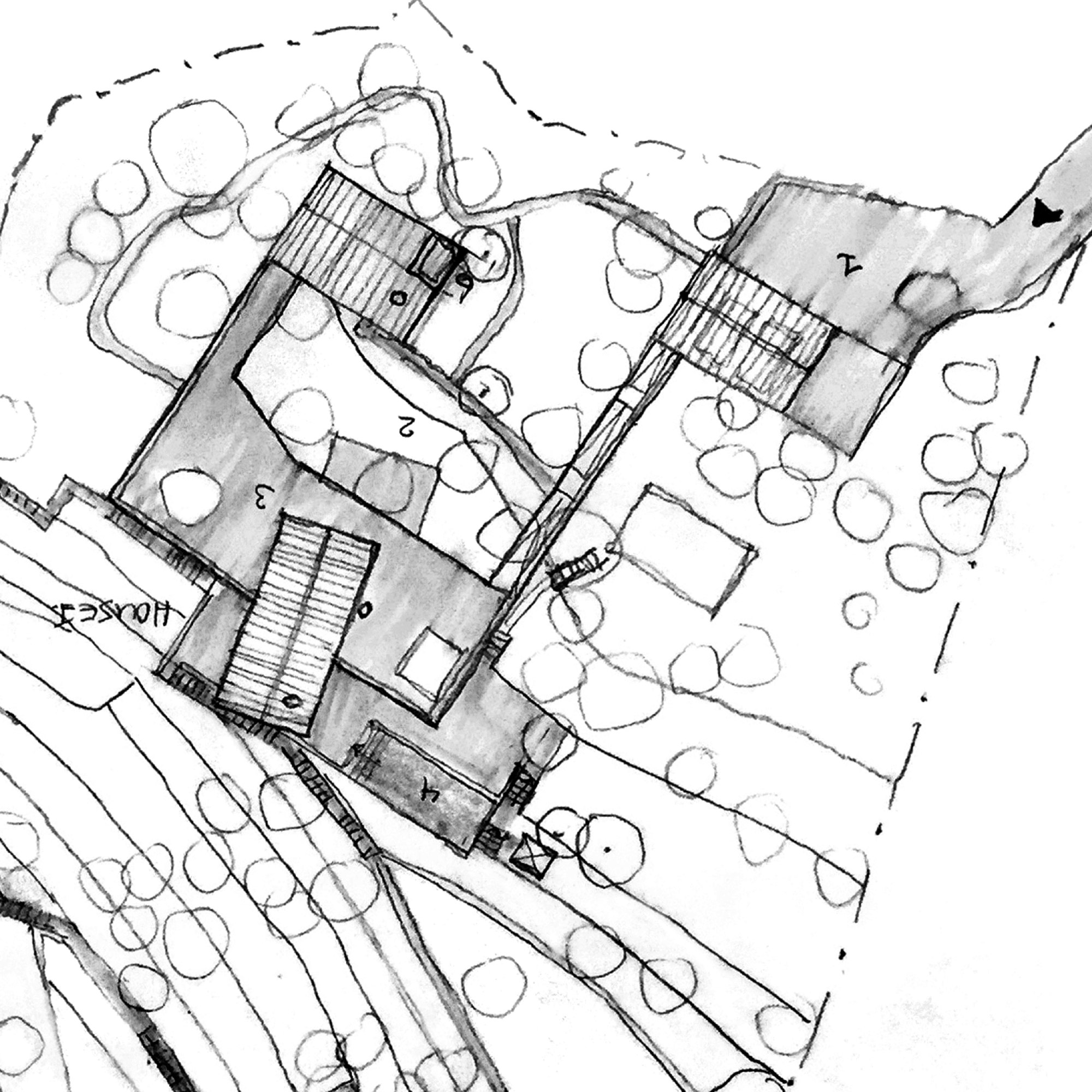

SB: After working in Sri Lanka (three years for Robert and a little over a year for me), we knew that we wanted to start our own practice together and at that point, it was a question of where and which city we should do this is in and the thought of living in Mumbai at that time was exciting for me as well as Robert. He was interested in continuing his journey more in the Asian context and maybe he was not ready to move back to the Netherlands yet. So, we chose Mumbai, and initially the projects which came to us could have been because people knew we had a certain background; they all were set in pristine landscapes and locations.

Whenever we went there, we knew immediately that for us this was a big responsibility to build anything there. We did not ever take it lightly; it was never about a projection of our egos onto a certain land or a landscape.

We knew that the visual criteria were not the end goal, it was the process and how you arrive at what the building looks like and blends in and occupies the space responsibly; not responsible only to the land but also responsible to everyone who looks at that building and to everything that surrounds it.

<14:46>

RV: We have never really designed a house that looks like a house; it is how it is designed in a way that it feels like something else. Maybe it is a change in scale, maybe it is a change in proportion or the non-ability to identify building elements within architecture, not being able to identify windows as windows or floor levels as floor levels, or a roof as a roof. […]

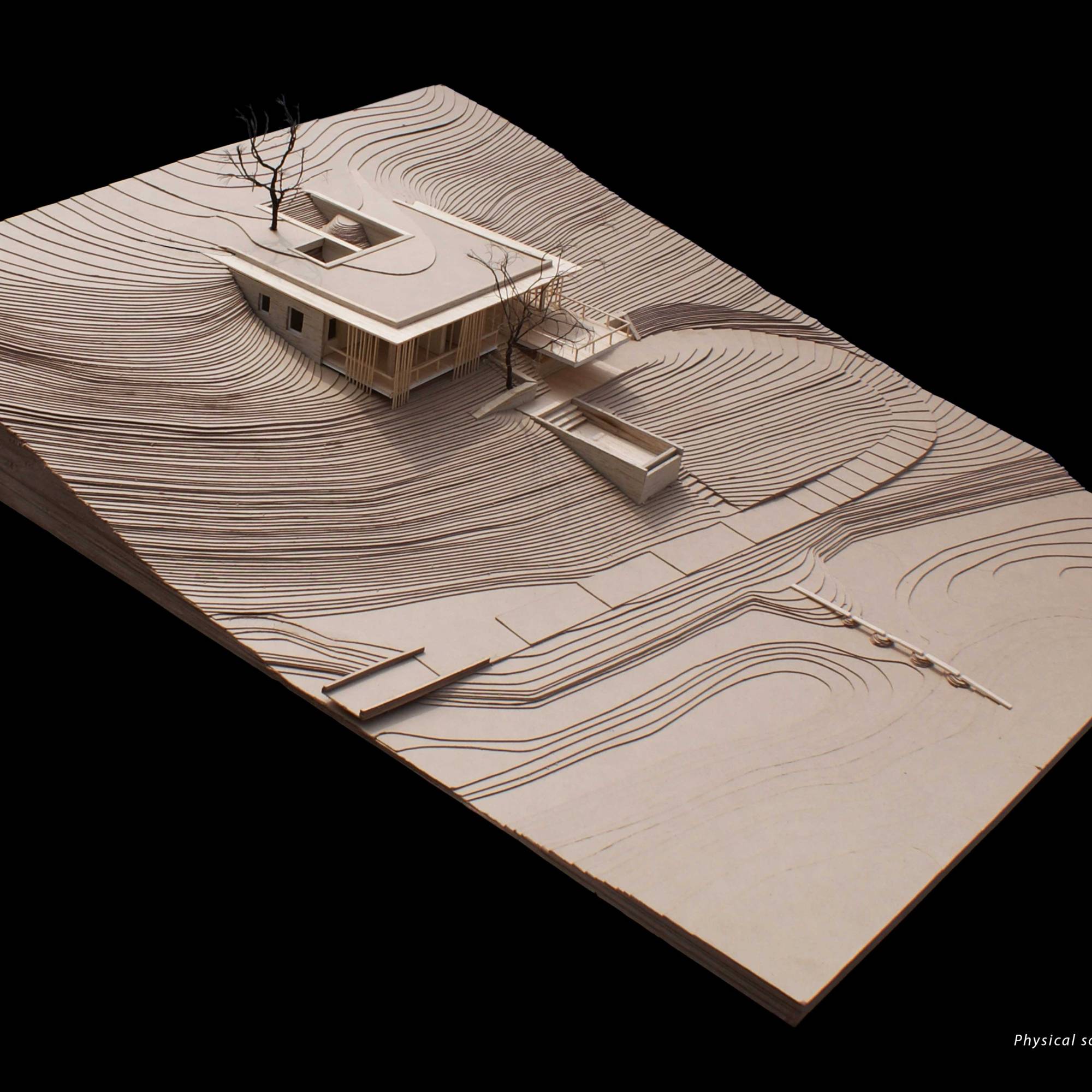

For example, in the House on a Stream, the house is broken up into two different parts. They are broken because it reduces the scale of the house and by doing that these elements of the house almost feel like boulders scattered around the landscape hovering, partly cantilevering, off-balance on the edge of that stream, where the stream runs underneath it. It has these tentacles that reach out almost like insects moving into the landscape between the available space in between the trees.

There is the Riparian House where the top surface of the mound is sort of lifted up and the programme of the house is pushed down underneath and it is more like a chameleon hiding between the weeds and is overlooking the river passing by and waiting for the right moment to attack.

One of the latest projects – the Plantation House, The Ray, which is built on top of a hill had a much larger programme than the first houses we built. So, we knew that the strategy there to make this building disappear would not work by the sheer scale of it, but what we could do is try and make the building look more like a lost ruin in the landscape; like a platform terracing that appears slowly from the contours and wraps around and disappears again. At some point it starts becoming a building with a typical, archetypal pitched roof elevation but then we counteracted it by carving out almost a grotto like entrance portal towards one of the bedrooms. This made it feel like it is not a building anymore, and it becomes like a grotto carved out of the rocks over there.

<19:10>

SB: With the kind of projects we started getting being primarily in the residential field, the human experience became another very valuable layer. It also influenced how we experienced the inside spaces versus just our response to the site context and surroundings. […]

We arrived at symmetry being the guiding principle of any given space. We did not want this to be a single narrative that you arrive at […] we wanted many small narratives to be woven into a story, movie or a book, slowly unfolding into a climax point.

[…] We are interior designers with an architectural background and our interior is very much about space and the experience of modulating light in a space, and how spaces are used and enhancing the human experience.

CULTURE

<22:06>

SB: For the first ten years, we were relatively a small practice of about ten people. This has been our studio strength from the beginning and around 2016, we had to scale up. We had some foreign architects working with us, so we reached a maximum studio strength of twenty. We also started working on competitions and exhibitions because although we were interested in those ideas, we had never found the time in our professional practice.

When Covid hit in 2020, the structure of our practice changed considerably; just before Covid we had again scaled down to about ten architects, we had a flurry of inquiries and had to scale up, so we grew back to a twenty-person office. Between 2020 and 2022 is when Mimo and Rohit both joined our practice as part of our senior team as partners. We are now between twenty five and thirty architects in this office.

Initially when it was a ten person practice, Robert and I were directly involved with everybody, be it interns, architects, senior architects and spent more time.

Now, we have a bit more hierarchy, we have senior architects, then junior architects, which freed up our time from delegating a lot more in the training and teaching to other architects in the practice, and focus more on the conceptual, ideating and design side of the practice.

<27:38>

MS: When we talk about the site processes and systems, we typically like to engage in the full-scale realisation of the project. It is all about showing them what it is about in a full-scale mock-up, whether it has got to do with a certain material or a specific colour. Something that looks like something on a piece of paper, will look completely different on site. We also try and encourage them to have it done on site itself. Because typically, when you do it inside a site an urban environment and when a site not in an urban environment looks very different under different conditions.

<29:30>

RV: Moving to the Netherlands allowed us to continue our explorations in our creative way of thinking about our work, where what we find interesting about working in India, is that we continuously are exposed to in these very different extreme relationships and contexts and climates and landscapes, and India is such a diverse country […] we worked in the Himalayas, in the coast, in the desert in Kutch and every time you have to reinvent yourself to engage in a meaningful way. In the last five years we have also done projects in Malaysia, projects in Philippines but it has still been in the tropical domain of the world.

Moving to the Netherlands allowed us to challenge ourselves again. It was almost like a reset button. How do you now practice and think about architecture in this very different context? — which I am of course familiar with, but I had to get reengaged with it in a way.

That has been very exciting. We have started our first project in Switzerland and what is surprising and interesting about it is that we think of Switzerland as being an extremely different country than India. Opposite in terms of wealth, but as you practice, there are also so many similarities with practice in India. Whether there are municipalities that are difficult to deal with or working with legislation or working with craftspeople, which surprisingly in Switzerland is still a very common way to work directly with the people who build, with the masons, with the carpenters the way we practice in India of course.

PROCESS

<33:36>

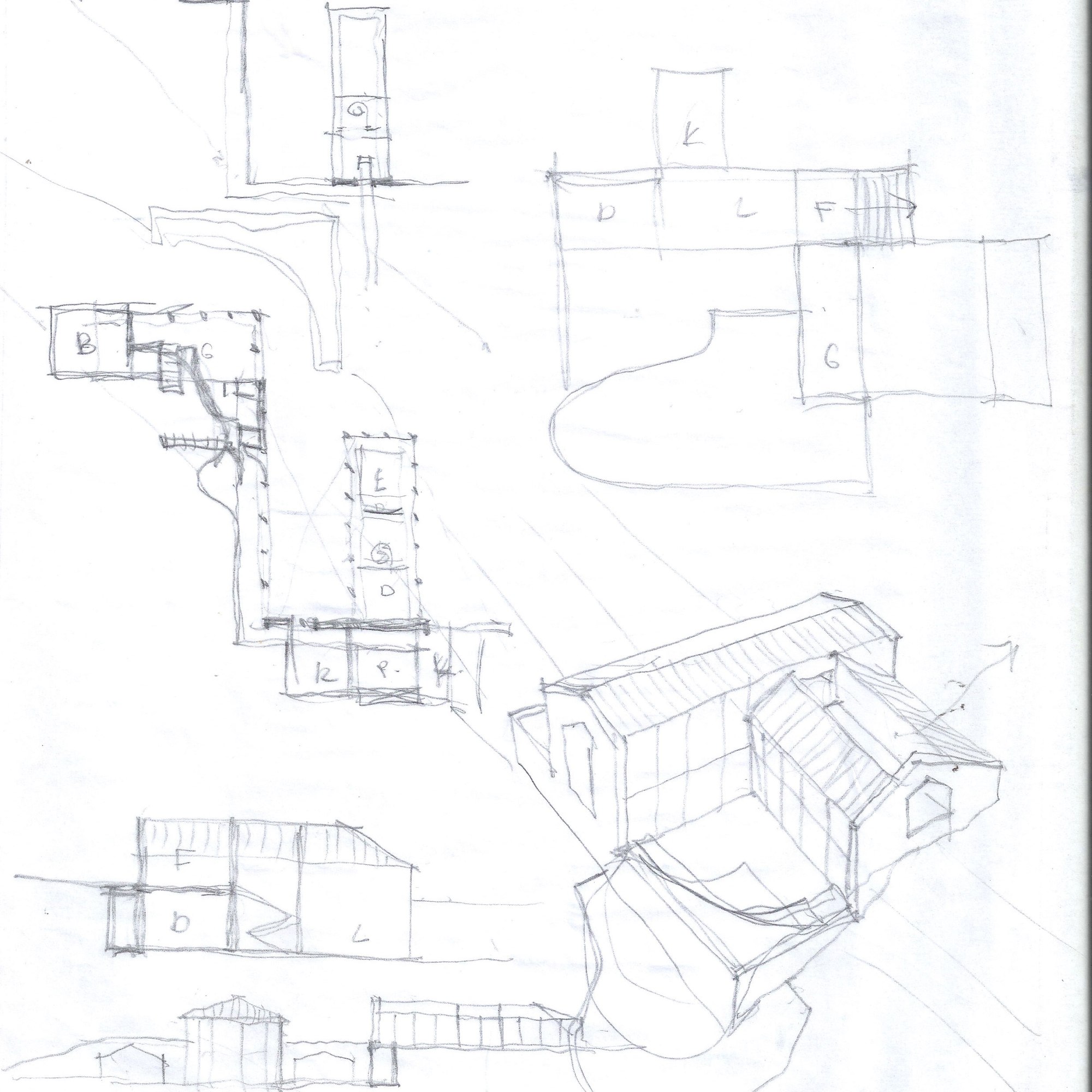

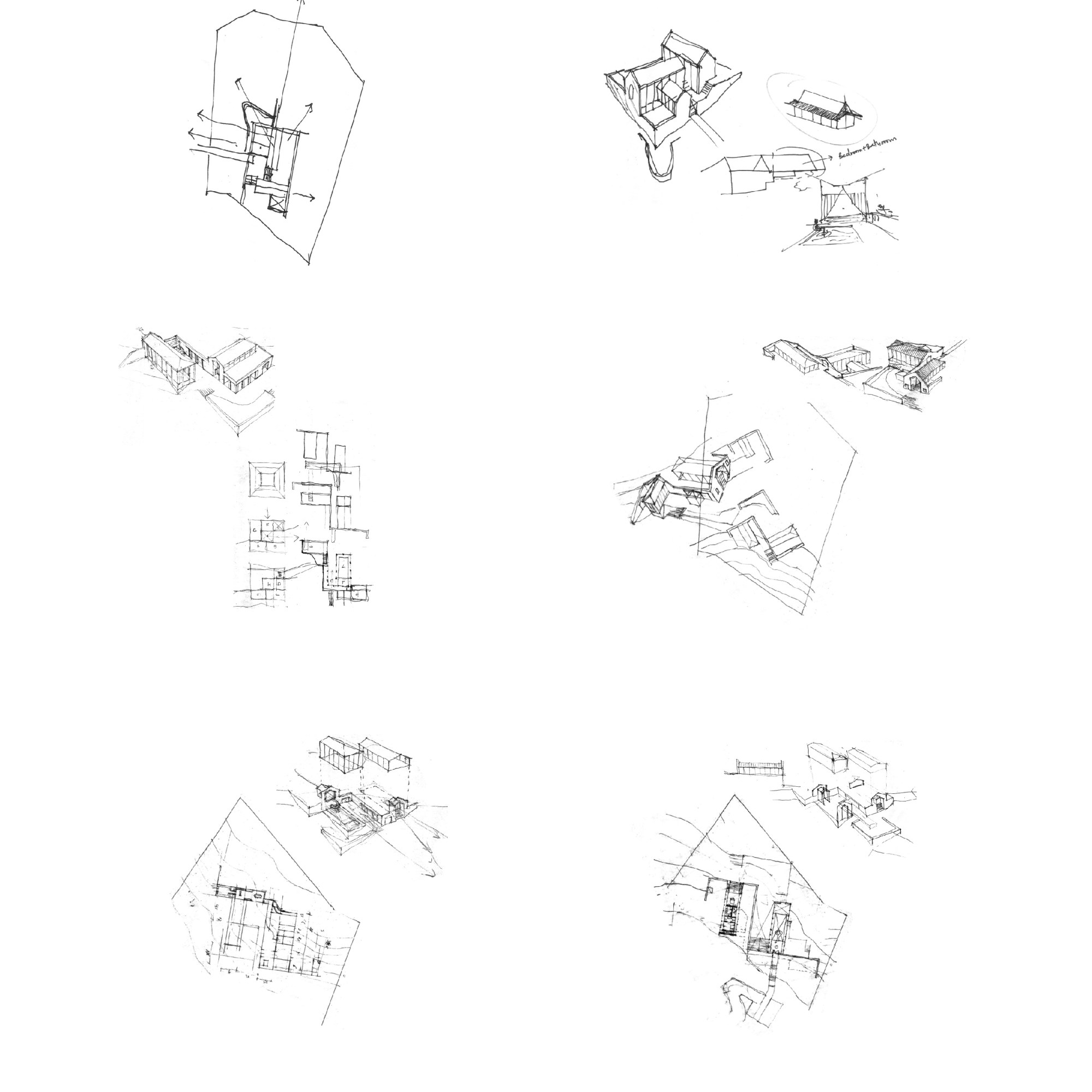

SB: For any given project we have found, with the experience that we had, there was not one right solution or outcome or approach.

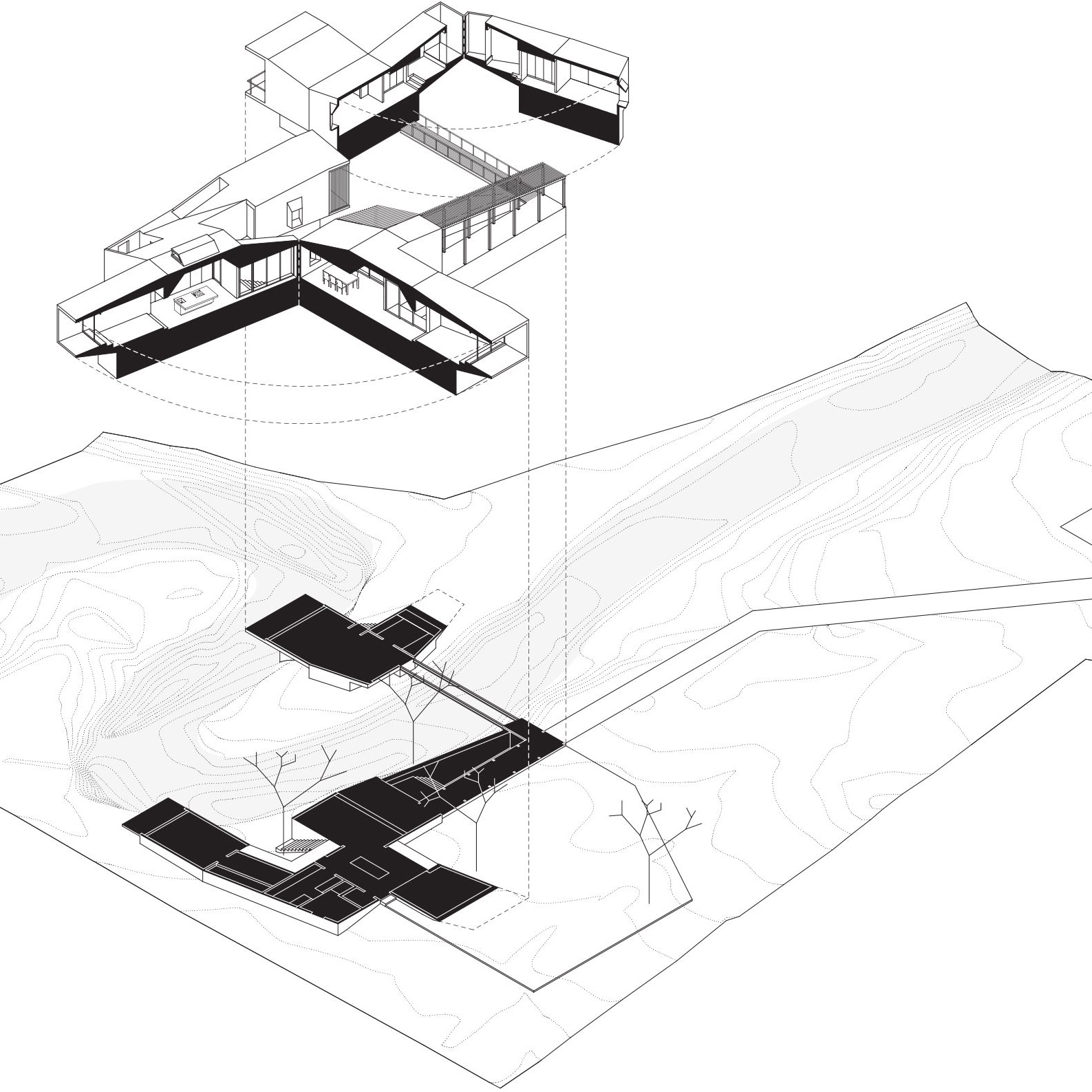

For us, it always starts with a diagram, the floor plan and ideating on configurations.

Often, we have several diagrams we find exciting or interesting. Sometimes there will only be one in the end which we think is the right choice but more often, we always have at least a few options and then very early on we like to engage on the design process with the client and present these to them, so they feel as much a part of this process as we do.

<35:34>

RV: In the early years of our practice, the motivation for architecture was for it to be purely built toward a context, influenced by the natural landscape. We saw architecture as a way to deepen that experience. But as we also saw how architecture was being built, what materials were being used and how scarce these were becoming.

We realised that there was a way to put more emphasis on how architecture is being built and what the building culture of the region is in which we are building.

You see that in projects that are designed at a later stage which have more exploration of different materials that are being used. Materials that use less embodied carbon. Replacing, for example, brick by a local stone in a project in Kutch recently or the project in the Himalayas where we have completely eliminated the emissions that are being put out by transport by using the materials of the site itself. The walls are built out of the rock that came out of the foundation excavation in the project.

<37:15>

SB: Another example is the Artist Retreat that we did in Alibag, because that being a coastal zone, and a flood prone zone, we knew from the beginning and that we had to make a structure that is dismantlable and that was lifted off the ground because in this very fast changing coastline of Alibag, you do not know if twenty years from now, whether that land or sea. We had to be conscious of the client’s investment into that and that guided our choice of material and our design process.

We built the structure in galvanized steel which is put together with nut bolt joints. There are no welding joints used, so it can come apart. We have used a bamboo structure for the roof on the inside and the outside is a layer of shingle coating. The deck itself is made of recycled wood, and the whole structure is perched upon stone boulders, which we happened to find on a site nearby which were not being used and we thought this could be an ideal home for them. The boulders added a different dimension to the structure. We could have, of course, put it on a concrete foundation or pedestals but we thought it looked more elegant this way and it somehow occupied and belonged to the land better sitting on a set of boulders versus a concrete foundation.

<39:59>

RM: BRIO would love to be involved in projects which are situated in a very strongly cultural location and a site-based context. We actively seek projects which give us those context challenges to be able to build in all kinds of remote locations.

Secondly, to have an economic and programmatic complexity to project. For example, low cost housing – because of the finances, the complexity of programmes, it is a much more challenging project typology to work on. We also do projects which enable us to do research on various methods of techniques of building. Every project is tailor-made, it is looked at with a new lens. We unlearn many things in the process which makes our team grow even faster.

<41:41>

RV: In our studio, there is quite a strong emphasis on the residential domain and I think about 60 per cent of the projects are private residential. But about 40 per cent of it is actually other types of projects, ranging from large multi-family housing to small boutique hotels, master planning projects, artist studios, etc. We have worked on a few urban public projects with The Bandra Collective and with an organisation called BillionBricks, who work on homes for under privileged and home for homeless but also affordable housing in India and abroad in Philippines. For example, we have developed a prototype with BillionBricks for a house that finances itself. By the power that is generated by the roof of the house, the house construction is getting subsidised. […]

<44:12>

RV: Generally in our culture there is still a very strong sense of the need to control the landscape in a permanent state. For us, we really appreciate gardens, landscapes, and for architecture to evolve over time, to mature over time, to appreciate in quality over time. […]

By the very fact of aging, by the fact that it will become overgrown, by the moss growing on the walls and the vines taking over, the architecture itself disappears.

<44:57> SB:

The success of a building for us is how gracefully it ages and how gracefully it occupies or belongs more and more to where it is located in.

Images and Drawings: All images and drawings are courtesy of Architecture BRIO unless specified otherwise

Filming: Accord Equips

Editing: Gasper D’souza, White Brick Post Studio

Praxis is editorially positioned as a survey of contemporary practices in India, with a particular emphasis on the principles of practice, the structure of its processes, and the challenges it is rooted in. The focus is on firms whose span of work has committed to advancing specific alignments and has matured, over the course of the last decade. Through discussions on the different trajectories that the featured practices have adopted, the intent is to foreground a larger conversation on how the model of a studio is evolving in the context of India. It aims to unpack the contents, systems that organise the thinking in a practice.

The second phase of the PRAXIS initiative features established practices in the domain of contemporary architecture in India.

Praxis is an editorial project by Matter in partnership with Şişecam Flat Glass.

Şişecam Flat Glass India Pvt Ltd

With a corporate history spanning more than 85 years, Şişecam is currently one of the world’s leading glass producers with production operations located in 14 countries on four continents. Şişecam has introduced numerous innovations and driven development of the flat glass industry both in Turkey and the larger region, and is a leader in Europe and the world’s fifth largest flat glass producer in terms of production capacity. Şişecam conducts flat glass operations in three core business lines: architectural glass (e.g. flat glass, patterned glass, laminated glass and coated glass), energy glass and home appliance glass. Currently, Şişecam operates in flat glass with ten production facilities located in six countries, providing input to the construction, furniture, energy and home appliances industries with an ever-expanding range of products.

Email: indiasales@sisecam.com | W: www.sisecam.com.tr/en