An editorial project by Matter in partnership with Şişecam Flat Glass, PRAXIS investigates the work and positions of diverse contemporary architecture practices in India. In this episode, Avinash Ankalge and Harshith Nayak of A Threshold, introspectively examine their practice from the perspective of evolving from a multitude of lived experiences over time. These vignettes link their work’s ability to look consistently towards traditional depictions and landscapes, their mentors, and travel in terms of cultivating dialogues, and exploring experiments in spatial systems and details. They connect their processes of sketching, making models, seeking exchanges in architecture and teaching back to these guiding impulses. In invoking the various inferences, they form a worldview of an architecture of – possibility – that has more to do with the stewardship of gained knowledge and steering it towards making new kinds of relations with the programme, light and public.

EXCERPTS FROM THE INTERVIEW:

AA: Avinash Ankalge

HN: Harshith Nayak

FOUNDATIONS

<00:00.26>

HN: I studied architecture in a place called Tumkur, at the Siddaganga Institute of Technology. During my final year thesis, Bijoy (Ramachandran) Sir was our juror. After the jury, I applied and got into his office for an internship, and I rejoined there as an architect, and we continued to work together for five years. That shaped what our principles are in terms of the way we practice, and how we set up our practice as well.

AA: I remember our school teacher during my school days, […]. In terms of drawing, she was the one encouraging and motivating. I was quite fond of drawings and paintings during my school days, and she was that one teacher guides you and directs you. I must always remember her as a starting point of going towards this profession of architecture, or the art of architecture.

I studied in D Y Patil College of Architecture in Pune […]. During my second year, we had to do a case study of one building or one small-scale house. We met Architect Girish Doshi in Pune, and I saw his studio. […]. It was a little underground, and since he had worked with B V Doshi, and many principles of Sangath reflected here; how you go down, and discover yourself.

It was very intimate, like a family atmosphere. We also studied his project, Khadke house. He often speaks about the traditional Indian architecture in Pune – there are courtyard houses called wadas. It is like a central courtyard, and then there is a system of rooms, and then there are these two narrow staircases which go up. The Khadke House was based on those principles, and then from that point onwards, I got fascinated with vernacular architecture, which revolves around the basic principles of climate, culture, and aspirations. […]

AA: I started reading more about vernacular architecture and traveling more in India. After graduation, I briefly worked with Architect Prasanna Morey, PMA Madhushala for six months. During those six months, I learnt a lot from him; for example, how to approach architecture passionately. The way he rigorously looks at the subject in depth, it inspires me to this day as well. I meet them whenever I visit Pune, both Girish Doshi, and Prasanna Sir – and sit with them over coffee, and discuss many things, not only about architecture but also about life. After graduation, I worked in Mindspace, with Architect Sanjay Mohe. I worked there for ten years, from 2010, to 2020. Those years were quite remarkable for me, in shaping this entire journey.

I think some of those human values is what we want to take further, and we want that atmosphere of learning and a happy environment in our studio as well.

AA: I remember I met Bijoy Sir for the first time in my fifth year at Mindspace. Mohe Sir had invited Bijoy Sir to our office to present. I shared some of my drawings and sketches with him, of these buildings and wherever we travelled. Then he invited me to present this documentation in Hundredhands. After that, the conversation started, and I used to go to Hundredhands every Wednesday. During those events, I met Harshith there. We started sharing on what he is doing and what I am doing. During the exhibition of drawings at Bangalore International Centre, we met again, and then we shared what we were doing at present. […]

We started sharing and somewhere that idea started, that both our likings and our mentors, they are the same and the same values are imbibed in us, in our day-to-day. We discussed and thought to take these two values, join them together and look at a larger picture out of this.

We were constantly searching for a name for two years and what the name should reflect – the idea, the process or the philosophy of the entire practice. The name ‘A Threshold’ – is the threshold, transition of many cultures, many events, in Indian architecture. ‘Threshold’ as a word has a very cultural and sacred meaning to it. It is a transition from inside to outside and it is a transition from the east to west, north to south and it is like blurring boundaries between many things.

The in-between realms are what we wanted to have in all our projects, to have a feeling of the inside and the outside.

HN: Every project that comes to our office, has a larger idea because maybe in the initial years, we were concentrating on the smaller projects that we got, the residences were bound with limited sizes due to the plot structures in Bengaluru. All our projects have a larger idea in terms of how you deal with the same 30’ x 40’ or 30’ x 50’, or 60’ x 40’, with varied sections. Even though the facing is the same and the quadrants are the same, and the rooms also sit in the same place, how you get the light in each project is different.

AA: Bengaluru as a context, is a garden city. How do you respond to the garden city, in a tighter place as well? We started our first project in Bengaluru called Breathing Enclosure, which is a renovation project- not completely done by us, the building was already existing. The client came to us with a brief of having a facade-elevation design – we convinced him, and the client was very accepting in that sense, that we tried reflecting the sense of a garden city into that elevation. It is not a dead elevation of some cladding, it is breathing, which breathes over time. We have these vertical ferrocement troughs, which are all along the sides, and the internal spaces look out, and we got a verandah, which segregates the buffer between the outside and the inside, and the building is a complete enclosure with green. That was a start point, where we felt that in a tighter space as well, you can reflect the idea of a garden city.

As Louis Kahn always says – Light is like a material, how the Brick is essential for buildings, the light is also an essential material to evaluate the entire space and the feeling.

It is a combination of everything, making the section more porous and allowing natural elements to be part of the entire envelope. We have done around five to six of 30’ x 50’ plots, and most of them are North-facing or East-facing, and a few are West or South-facing, but every section is very different. But the way you vary the section and modulate the light, the wind will flow through that and the Bengaluru context allowed us to do that. The context is very tight, and you cannot look out more, you have to look in.

Moving further, we would like to have a scale variation, where we can have a small institution where you can transcend these values into public buildings, where more public nature is involved, and more and more people are a part of that space.

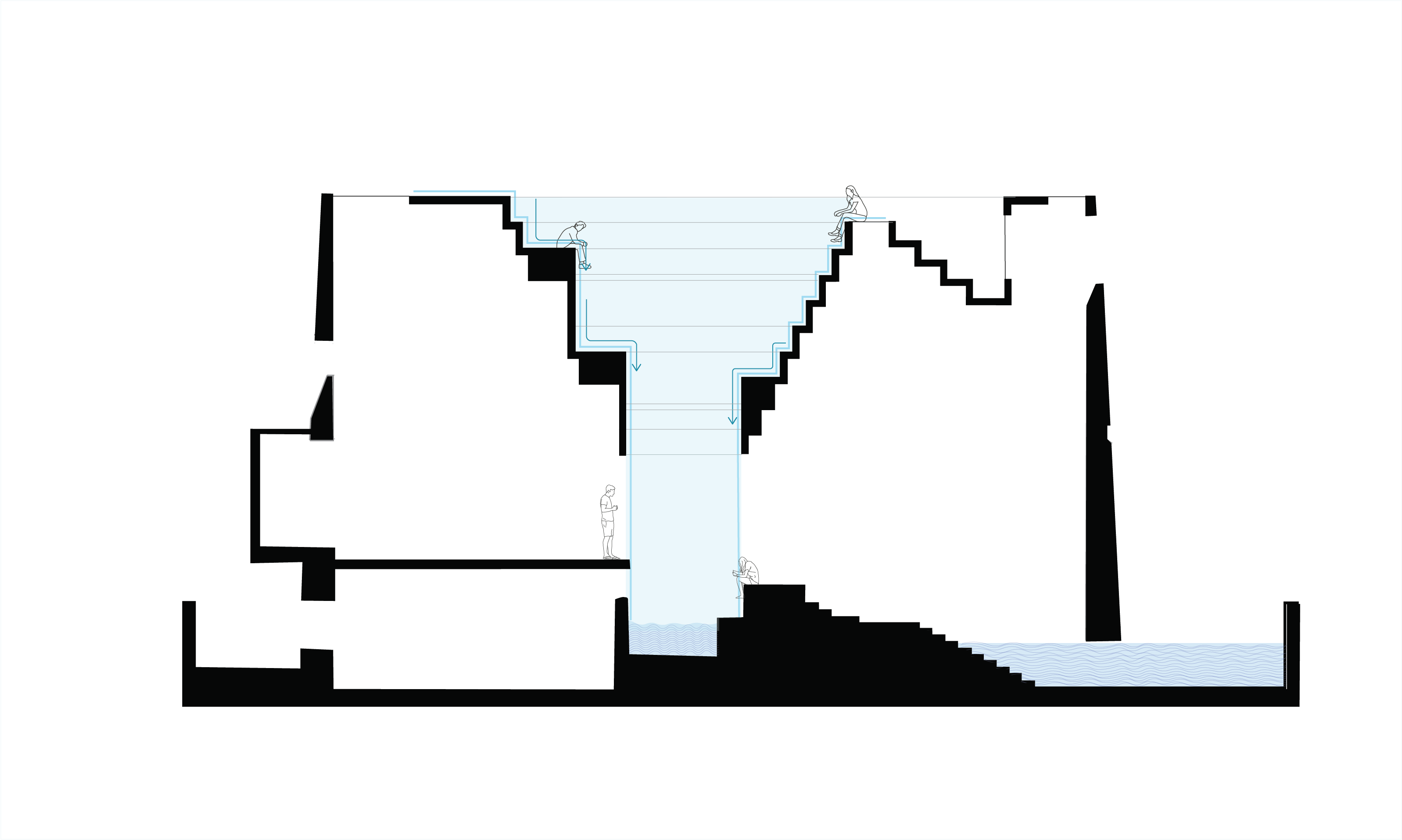

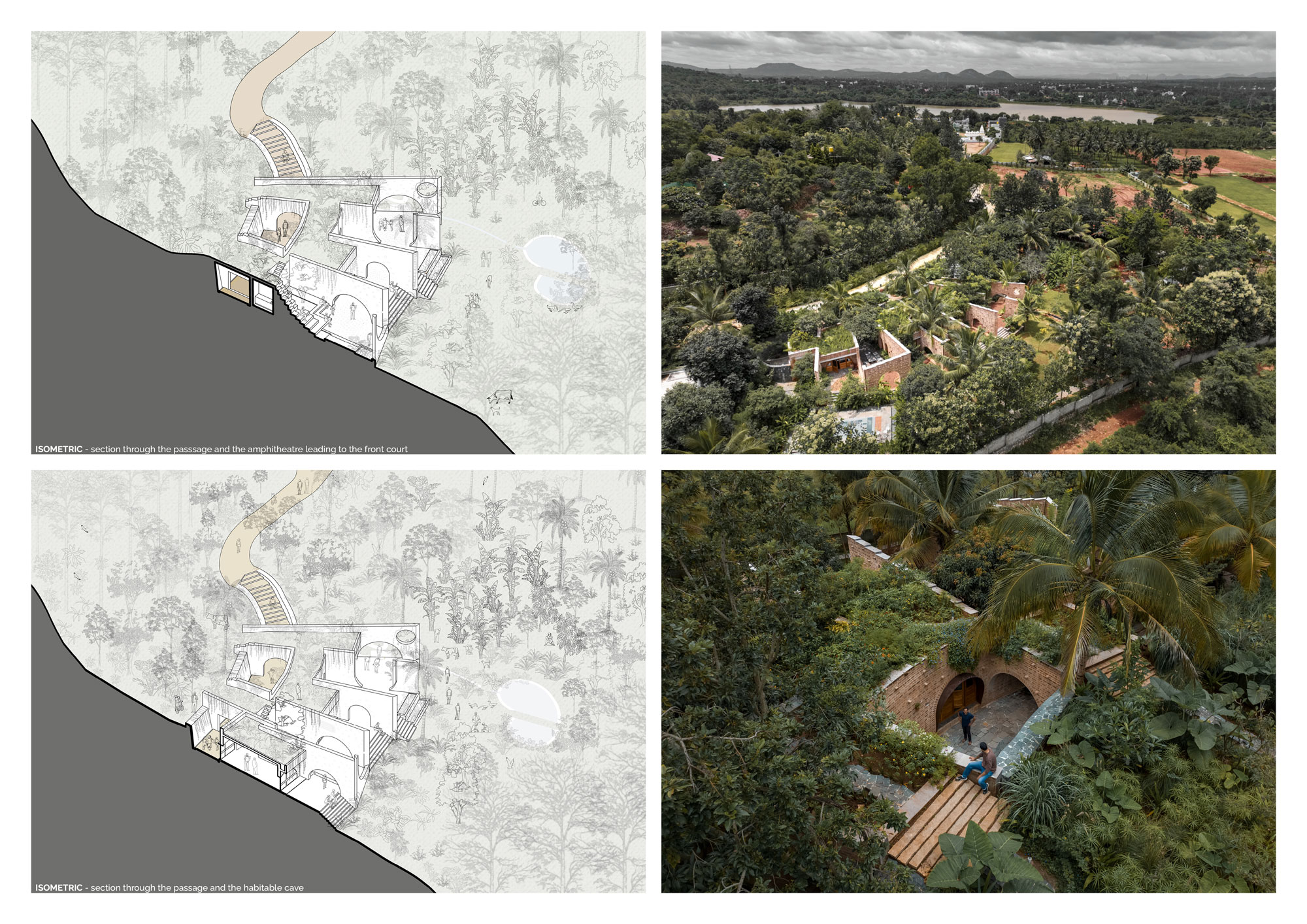

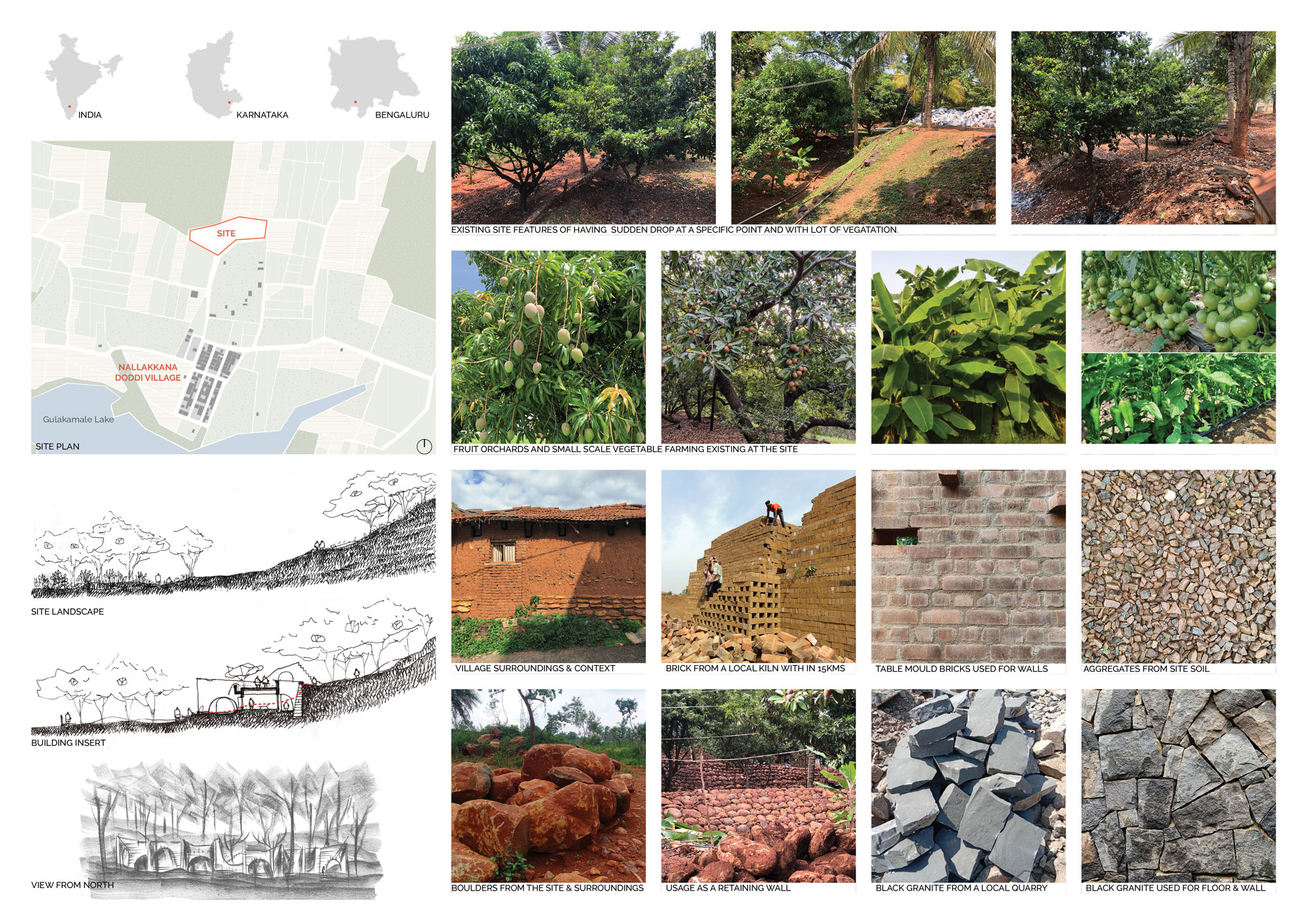

AA: […] In the case of Subterranean Ruins, a project we recently finished, it has a more flexible plan and is balanced. You have to have a client who is open to having all these public ideas, and we are looking forward to having other projects like that, where it is needed for the society – the community activities, and engaging more people within your activity, and the process of building things.

Louis Kahn, he has a very nice article about how you can stretch a brief. I just wanted to stretch this idea of space as a resource, where for example, in the project Subterranean Ruins, we have this planning system of four caves, where it is derived from the existing tree and the terrain, etc. The client came up with the idea of a house, but we slightly stretched the brief; that it need not be just a house, it can house a museum also.

There are many sculptors and potters surrounding Kaggalipura, where the building sits. We thought to include their collaboration into the building rather than having a dead farmhouse which people use only in the weekends. The plan is flexible, and where the built and unbuilt correspond. The same space can be utilised for events.

The client, Mr. Bhaskar is quite philanthropic. He has built temples and does many things for the local villagers there. He allows villagers to have events within the entire campus. We had a sculptor’s workshop one weekend for the village kids there. We also had a painting workshop conducted for kids. One weekend, a yoga teacher, one of the client’s friends, came and taught the kids yoga as well. The nature of that building changed entirely. The entire space changes over these temple events, or these kids having workshops, or it can be a small kindergarten or over the weekend, it could even become a farm stay. All these activities overlap into each other, without disturbing the active nature. I feel that space is a resource, while of course building materials have to be local, but in today’s time, especially in the metro cities, that space is becoming a crunch.

CULTURE

<00:17:15>

HN: […] We are a small team of 12, including the architects, the interns and the both of us. There is no such hierarchy saying that this trickles down from us to the junior architects. […] Everybody is involved in almost all the projects that they handle. Everybody gets their views to the table in terms of any small details, to the way it is getting executed; it is more collaborative. Not just in the office, but also on the site. There are so many different contractors coming in, inputs from the clients that come in, so all of them working together to achieve the larger idea, and the way our principles of each of the project is to be met.

AA: When you do a collaboration, or a teamwork, it is not one person; it is always a bunch of people working together. It is not like a painting where oneself is reflected into it. But there are many hands joined together and doing that together. Not only in the office, but also on site. The context plays a very important role for us. We are doing a few houses in the villages, and how the context from Urban houses to Village house is totally different in that way. But how you combine these values, to the sense of belonging, and the family structure, is completely different in the village and in the cities. And how do you cater these values into those built forms? It is quite interesting to tie these two things together. And I think it happens where the team, all of us, sit. As Harshith was saying previously, every project starts with an idea. It is a larger idea that varies in each and that idea, throughout the project, guides the design – we never lose the idea in between the process.

Like what Louis Kahn says, “From intangible to tangible, from immeasurable to measurable”. When you start, you have that immeasurable dream in your mind. During the process, it is getting through the measure drawings, and you negotiate many things with that. You make sure that you have that intangible idea throughout the project alive.

AA: And when it completes, at the housewarming, or the day of the pooja, we feel so happy, and we remember the first sketch – what we have drawn and the last visit to that site. It feels quite emotional, because you have put your efforts into that, and somehow that has reflected the five senses into that project, with emotions. In a way, we look forward to people feeling that it is their own project, rather than feeling like they are working for someone else. When you look at it in that way, you are putting all your efforts to get whatever you want. I think it is possible because we do not have the hierarchy. That gives us this flexibility, as we are young, to push those limits and boundaries to feel that it is our own work.

PROCESS

<00:22:06>

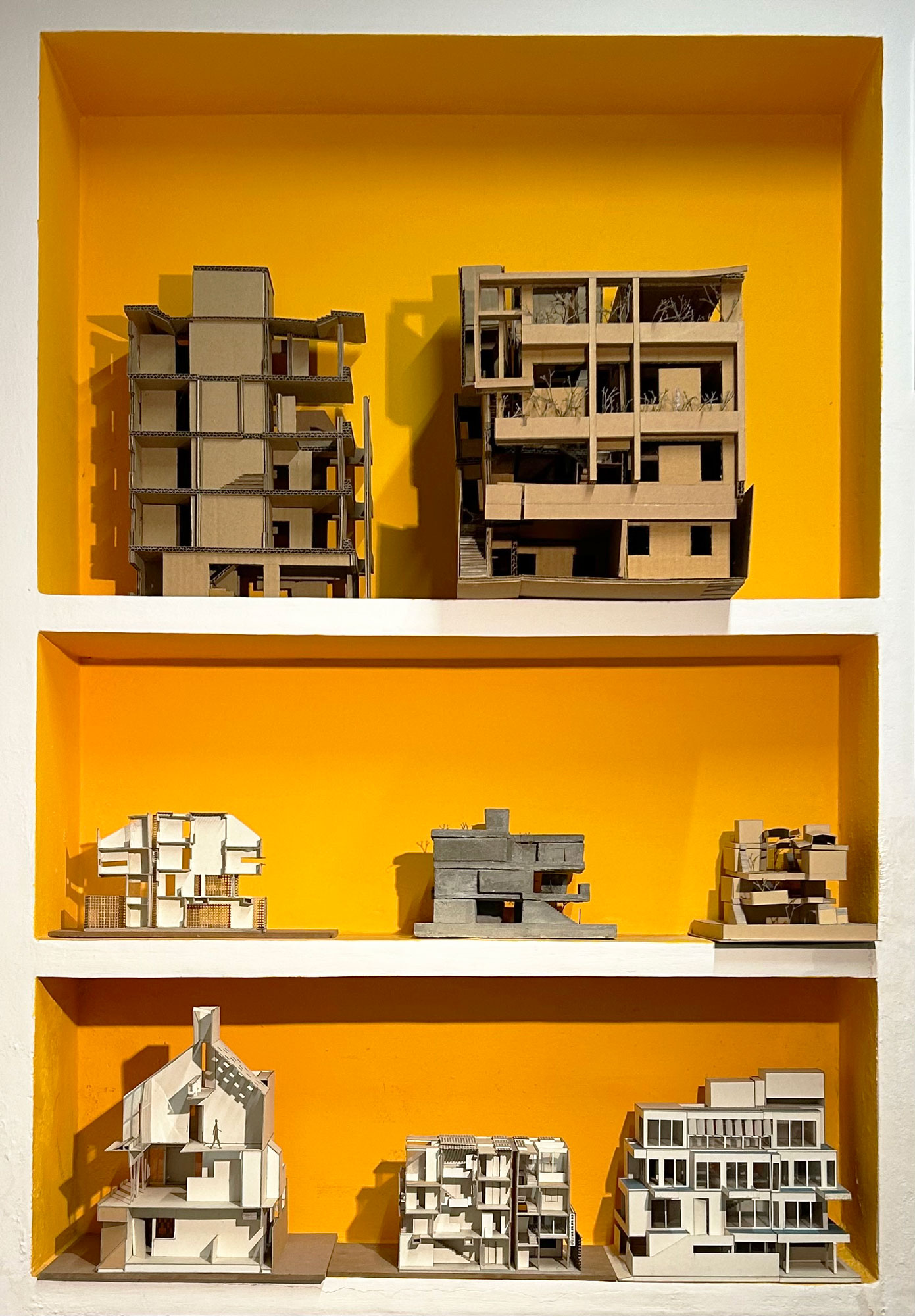

HN: The way we work is flexible in terms of the way we do models, making block models or hand sketches. It is not particular that each project goes through this process but rather based on the way the project is or the scale of it, this may vary. It might be a clay model or a concrete block model, to just understand the scales and spaces, as well as getting into details at every scale of the project is what each project goes through. In the last one to one-and-a-half years, we have lifted the scale from just residences to having institutions and hospitality in the category that we want to work in. Institutions always aspires both of us to work on, because it is meant for a larger scale of people, the number of users is more, and the way it impacts the society is in a bigger way than the residential category. […]

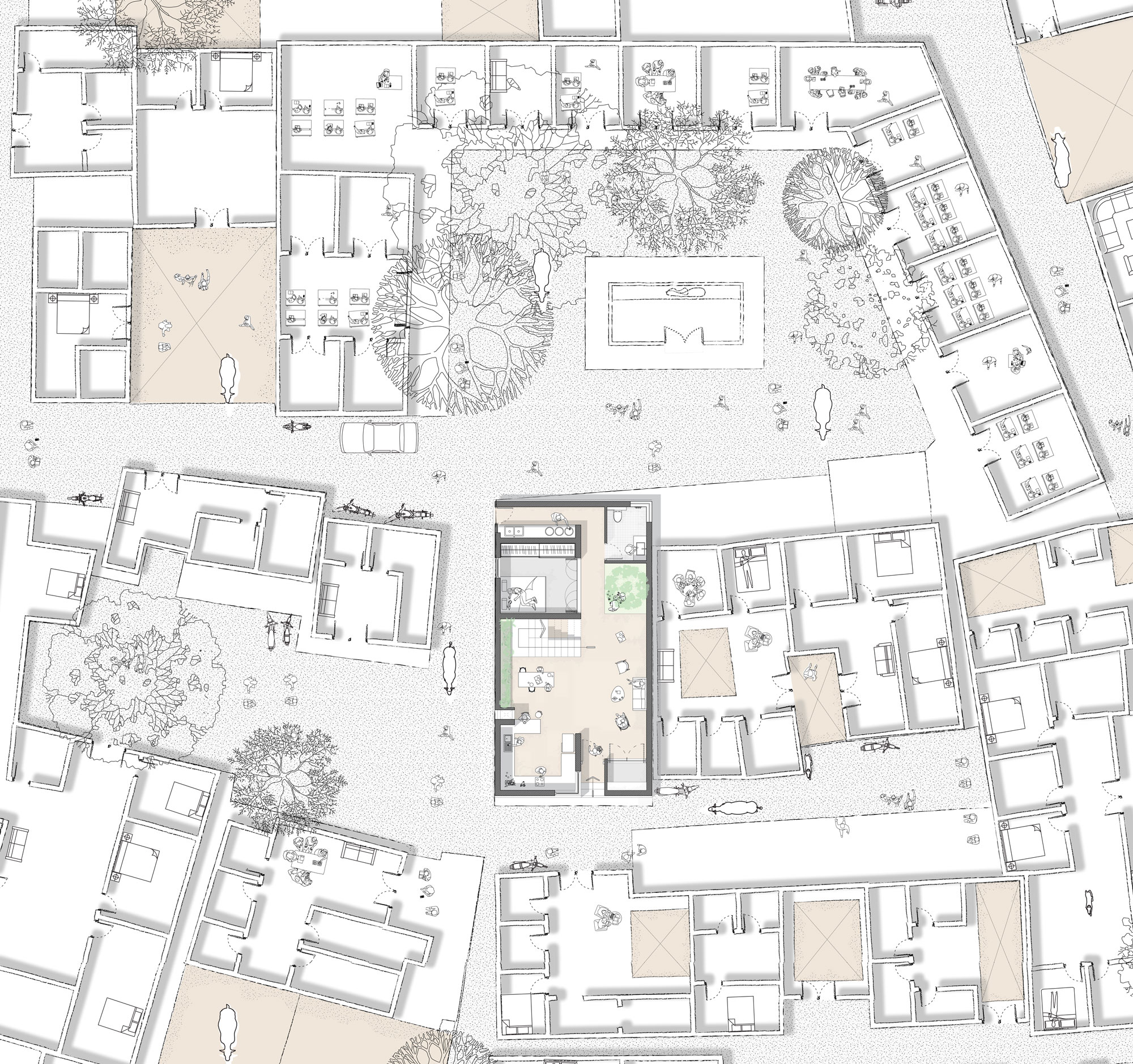

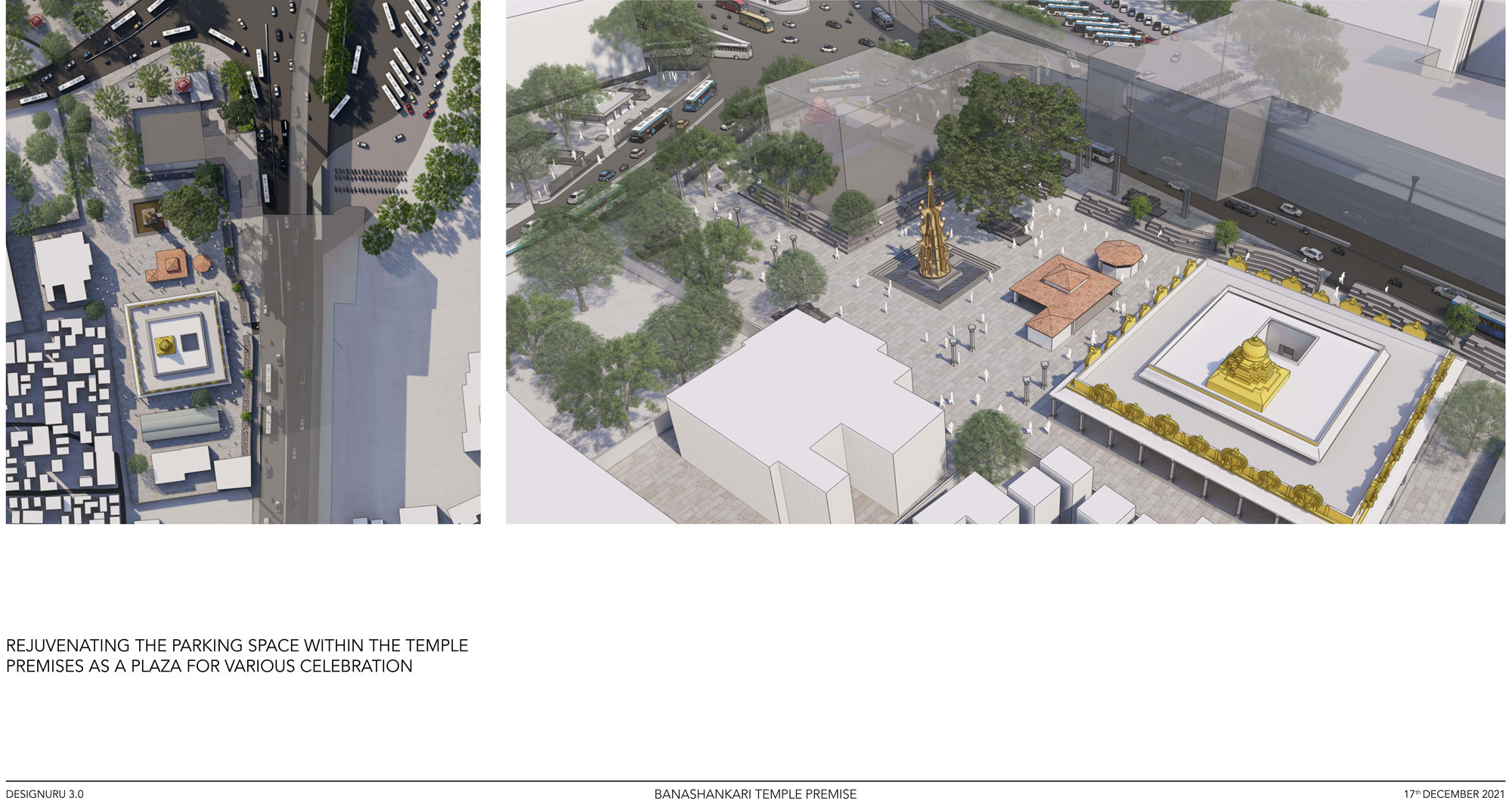

We had an opportunity during last year’s Designuru, the design exhibition that happens for a week in the city. We were to understand a small part of the urban scenario, Banashankari, which is a close-by neighbourhood. We had to understand a junction in the city, and understand how it works throughout the day, and changes throughout the week. […] The opportunity for us was to understand how to revive the small urban context, and so the scale varies in terms of a larger context. It was a good exercise for us since we had never dealt with such a scale, it was mainly a proposal from our end to push things for how a society can work or a segment which is public in nature can work. […]

AA: Initially, we started with some smaller-scale houses, and how the idea of a porous section transfers into a little larger size of a project, like an institution. […] We compared some 5-6 sections of our houses at the same scale, and how all these elements transcend.

There is light, ventilation, access to green spaces, and various thresholds at every level across. It is like a house within a house. It is an interesting idea, and how that entire house becomes a city inside.

The same idea translates when we were doing a small-scale institution in Pune, it is a school within a school. It is a large campus, and there are many schools within. But in one school building, you have many classrooms as a school – which is what Kahn talks about, as ‘a society of rooms’. All these things coming together, and how it connects to the larger campus, and that idea of a threshold, where once you are moving across that entire campus, you never feel that you are walking through a large thing, you are always connected across with multiple levels, and connectivity, light, and various volumes. […]

AA: We are also doing some houses in very small villages. These are some traditional vernacular houses. The context becomes very strong. It becomes more difficult to deal with that, because there are hundred to five-hundred-year-old houses next to you. How do you touch that wall and how do you build the next houses while catering to the modern-day requirements, with multiple levels? It is interesting to connect it back to your own travel knowledge, to what you have drawn and perceived at that time, and getting that to a studio, and then discussing with collaborators, and colleagues, you see how that connection is there, where we go back to study that, and come back, and how it must tie in modern-day times. It is very interesting, the whole journey and the process.

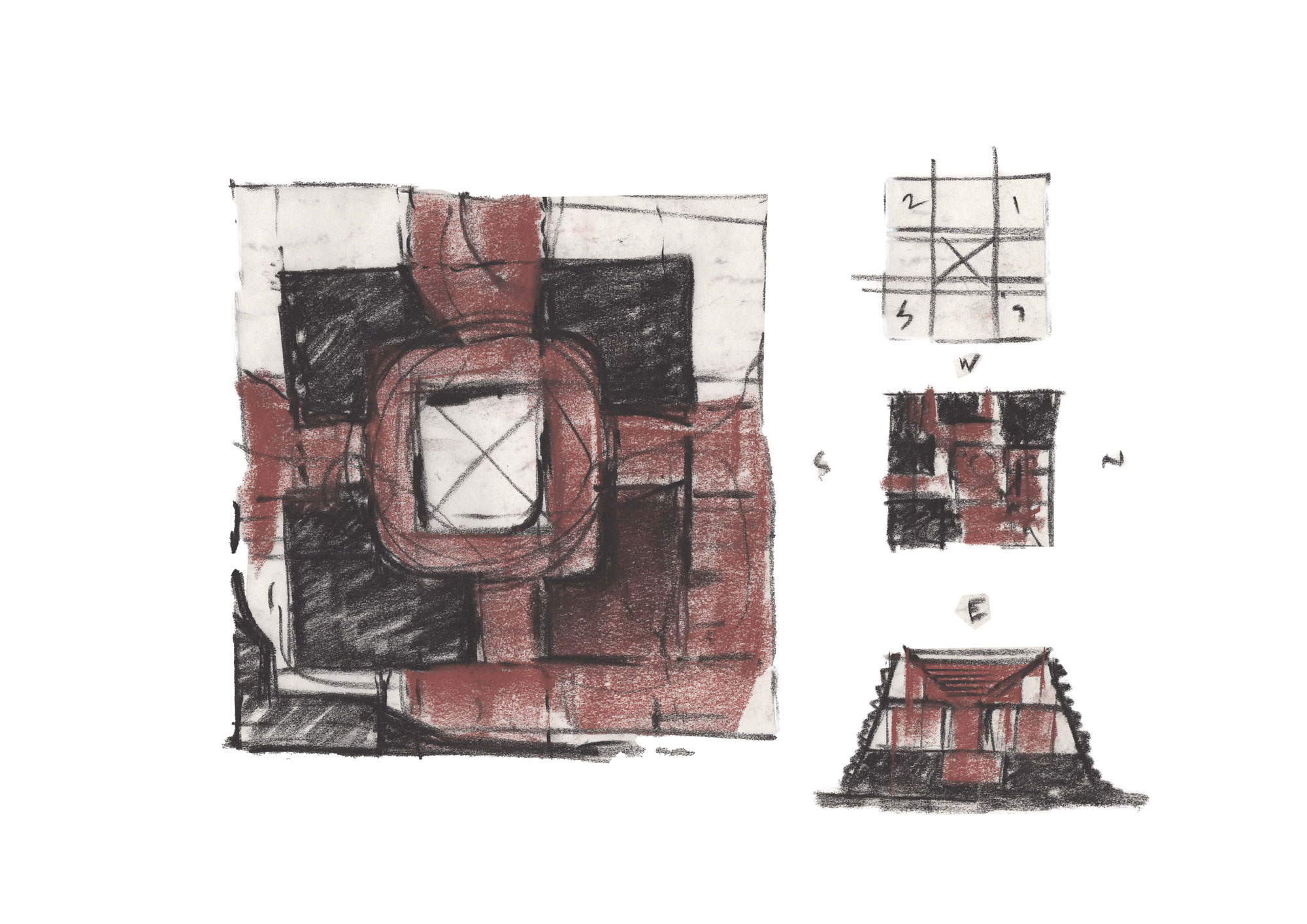

There is one house that we wanted to talk about which is on the ground floor or the first-floor stage, in Solapur, and there it is a very hot and dry climate. In summer, it reaches around 47 °C, and during our college days, we had visited this town called Shahabad, which is very close to that. During our travels, we have drawn many sketches, and sections of these houses, and the way Shahabad tied the material of stone, how it reflects that one stone for the entire building, and that one stone is multiplied in many ways – it becomes a rainwater spout, it becomes a wall, it becomes the floor, it becomes the roof, and it becomes a water tank also. So how that one module is repeated, to get that scale, to that entire house, and when you come out of the house, the entire town is made up of the same. When we were building this house, we wanted to have that idea of a singular material, because it is quite close by, and we wanted to use that stone to do that, because you get local craftspeople there, and utilise the collaborative artisans’ approach in your building as well.

AA: In every context, whenever we do something out of town, or in smaller villages, we see what specialties there are, or what the town is known for. Not only in terms of material architecture, but whether there is any specific art form they have done over time, and how to revive that through architecture. […]

During my college time, I came across these two books and they were quite important in this journey. One is Le Corbusier’s ‘Journey to the East‘ – that book is very important. When he was sixteen years old, he travelled to Europe, Turkey, and many places in the Middle East. He travels and compiles it as a book. Every night, he used to write this letter of conversation and dialogue, about what he had seen that day, to his mother. Those letters are also there in that book. It is very interesting; the way he explains it. The second book is the process drawings of Louis Kahn, where in his forties, he travels to see the Pyramids, Italy and other places. His watercolour, soft pastels and charcoal drawings are there in that book. After graduating, I worked with Mohe Sir, and there was a compilation of his sketches, it is called ‘Connecting the Dots‘. I think these three books inspired me a lot, and they inspire me even today.

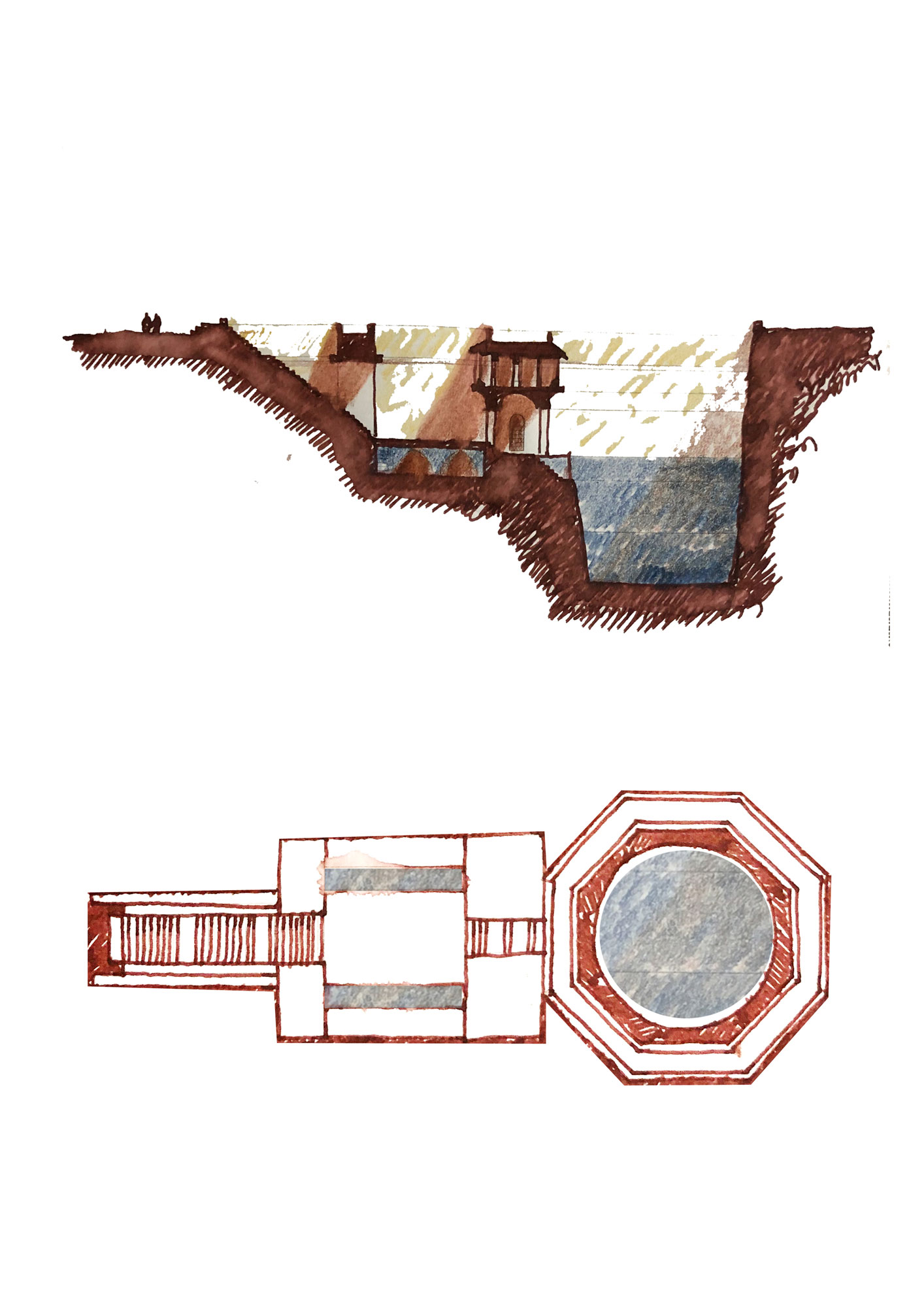

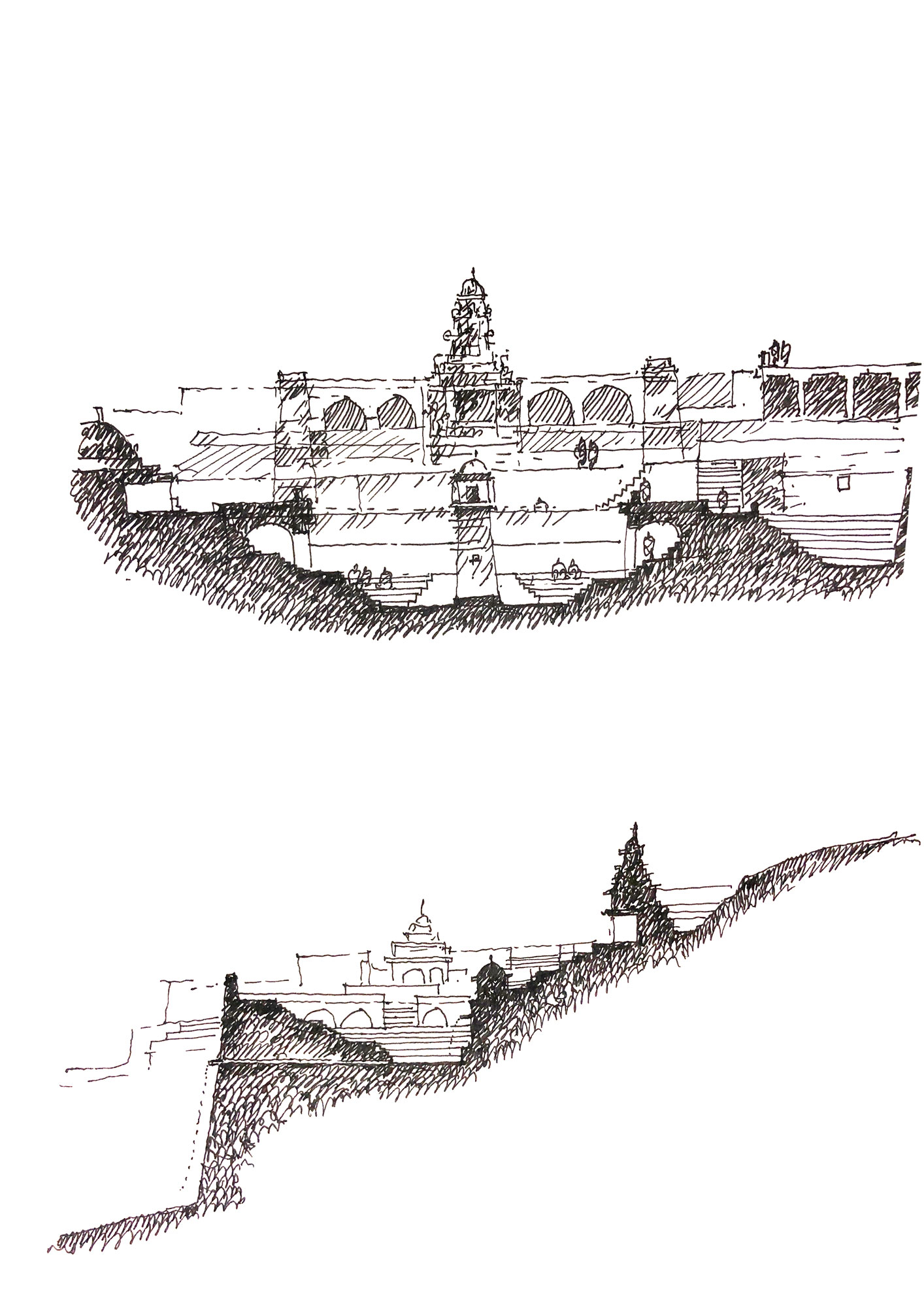

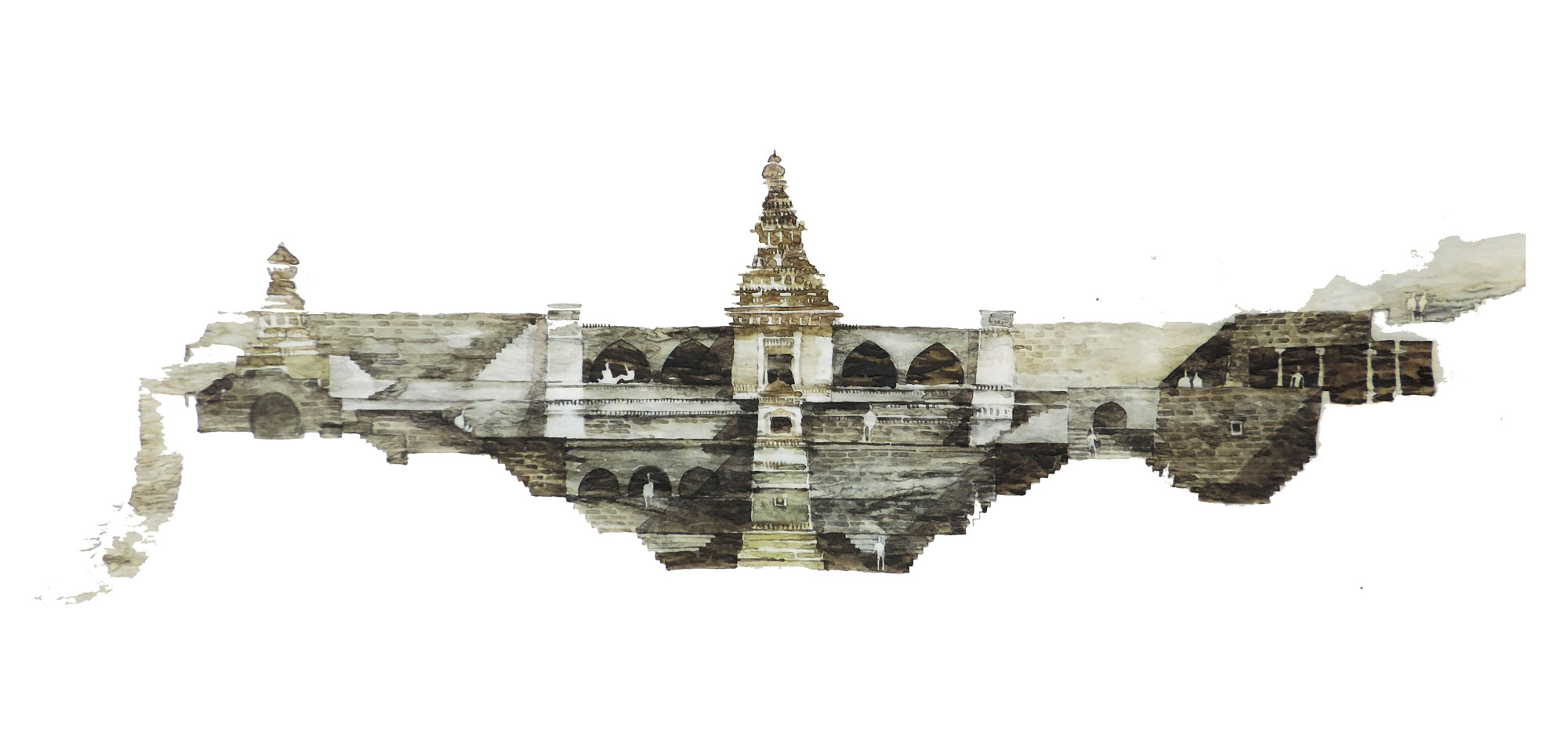

Through our travels, we try to do many measure drawings, and from our college time till today, we try to travel, and wherever possible, we try to document these unknown buildings, and measure draw them.

AA: I think that up till now, we have done some six buildings which are measure-drawn and documented in a certain presentational way. We would like to have a compilation of water structures, so we call it as ‘Steps to Water’. All are related to water structures, and how they relate to the entire city. It is quite interesting, that during your travel, when you look back, and when you are giving a solution to a particular project, and somehow it just feels that the solution comes to you – it is not subconscious, but when you are constantly in the process, these solutions come to you. It comes automatically, I do not know how, but it just tries to give you the solution at that point. I feel that the travel as a process, and as a journey, is very important to us as a practice. And how it tries to transcend that in today’s time. […]

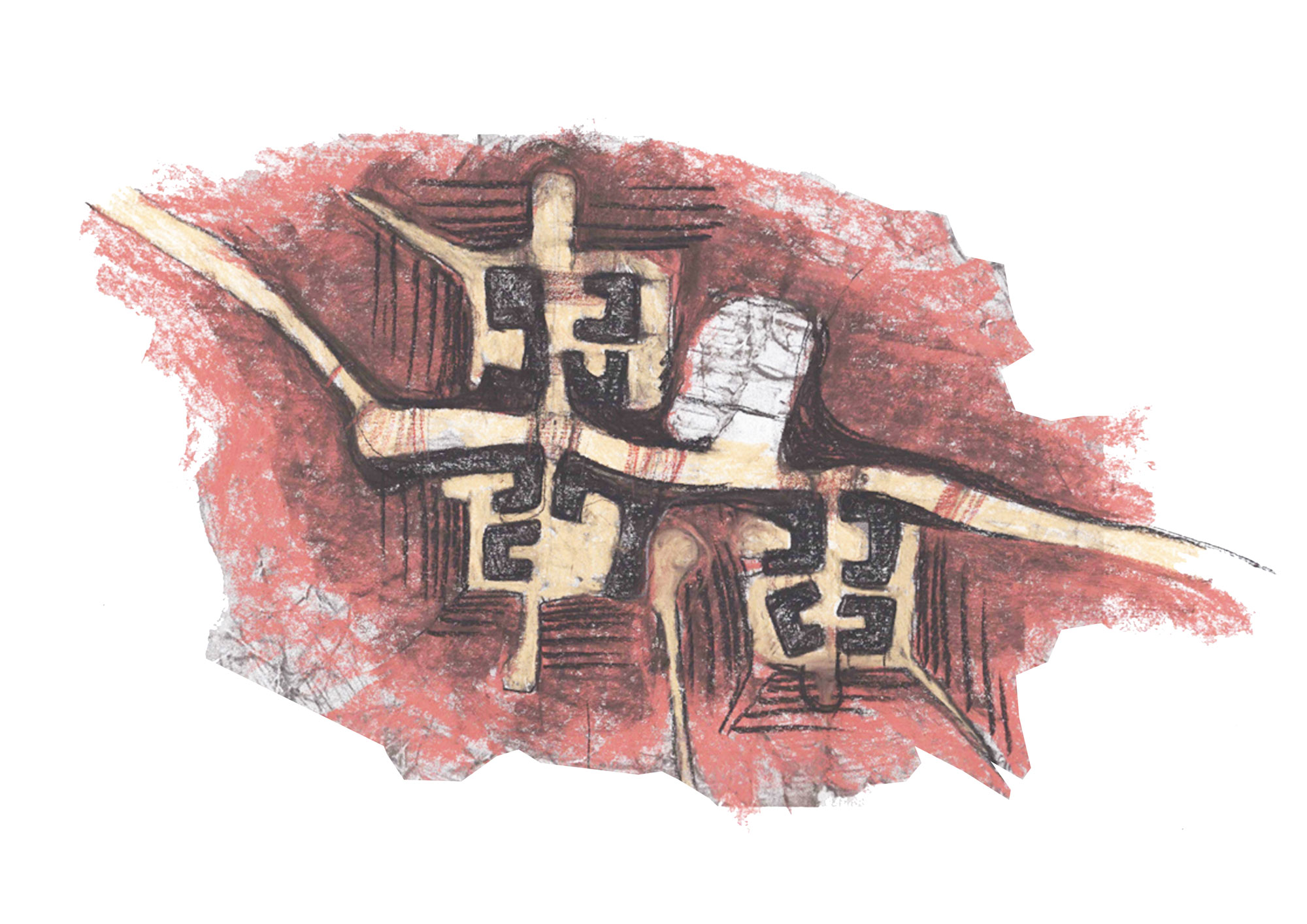

When you draw with your hands, you are aware of the scale. And sometimes when you draw or sketch your own project in that sense, your hand knows where to stop, because you have drawn certain things earlier.

AA: In the case of Subterranean Ruins, it was quite interesting. We had visited Ajanta and Ellora while in Mindspace, and college days as well. When we were doing Subterranean Ruins, and we wanted to present it in a week’s time, the entire terrain gave us a clue of how to look at that as a stretch. That same curvilinear path was existing on the Subterranean Ruins site as well. We just connected it back to that journey of Ajanta and Ellora, where the entire curve, and caves are sitting exactly in nature and how they solve the terrain. Your hand knows that very well – where and how it will fit. It was quite interesting to connect it back to what we saw during that time and the dimensions of the cave that we drew. And it just comes back to the drawing board.

The hand has its own memory – that memory is what the hand tries to draw.

I think it is a very important tool, for us at A Threshold to see how you try to connect back and how you try to engage that hand in this process of design. It does not stop there, whatever you have drawn, you try to measure it and put it into the physical sense, then a lot of physical models come into the picture. Sometimes, we start with clay, using our own hands. Instead of just measuring that entire model, let your hand get into clay, and just try to build with that. There is quite an interesting connection.

AA: Recently, we travelled across Varanasi last December with Mohe Sir, Kukke Subramanya, (P N) Medappa sir and Mindspace colleagues. It was quite interesting that over five-six days, every day we used to walk a fourteen-kilometer stretch of a ghat, and you come back in the evening, and sit across over the table, and discuss what each one has seen that day. To accumulate those five days’ knowledge, every day we used to discuss, and it used to be quite nice that each one has observed the same space in a different way. […] Whenever someone from our office travels or we travel, we show the slides in office and then ask everyone their views on it. I think everyone will look at it from its own perspective. It will be nice to document those perspectives, and see what we can do about it, or whether there is a way to contemporise it in today’s design.

HN: In Hundredhands, as I mentioned earlier, we used to usually have a presentation every Wednesday evening, about an architect that an intern is studying about, or by any practising Architect, or an artist who comes to visit, presents their work in the office, or even watching documentaries and movies. Even Bijoy sir’s brother, Prem Ramachandran was always pushing us to have a film club in the office, to look at a lot of documentaries, to understand and broaden our visions about how you practice architecture, to keep that creative process intact, and to widen the vision of having a creative sphere. I think that has shaped us in a better way. Even now, we try to explore in our office as well. We look forward to having such events and conducting such things.

AA: Sometimes, I take some workshops in WCFA, and whatever we know, we try to share with them. Many graphics workshops, and some measure drawing workshops we conducted there.

It is nice to see that collaboration on how you reflect where you travel or what you do in your own practice and try to share that knowledge with students and see what they think about that, and what they might take from that. It is learning in both ways, sometimes we learn from them, and they learn from us. It is an interesting process of sharing of what you know.

I think that any project, you start with an idea. But to retain that idea, you must cross many of these parameters. For example, once the design is done, you discuss with your colleagues and make drawings of it. Thereafter, is the time where you have to transfer that drawing into the consultant’s mind. Then the structural engineer comes into the picture, MEP consultants come into the picture. Simultaneously, contractors, carpenters, and craftspeople get into the picture. That one idea, you have to transfer to all these people. […] There are these ten parameters of your one idea – how you have that dialogue and have that conversation across the process. […] I think it is a dialogue, and there are many people in between this idea. They are there to discuss and shape this idea in many ways.

HN: In our project, Ineffable Light House, they planted so many trees and then the client sends us pictures of these birds making nests, and he is happy about it. At the end of the day, it is something that they have given that much freedom to use whatever materials we need in terms of how it needs to look and feel, and how the construction needs to be done. They just wanted a good home. Once that is done, they start enjoying that, and they become people who tell everyone that this house is like this, this is the way light comes into the house. There is a house in Tumkur, if you see, there is East and West light. The client also sends pictures showing early morning light falling this way. They enjoy that space, and there is variation because of the movement of light, and across the seasons. That is something we could say, is a measurement for a successful project, as an end user, and for us, something where the finishes have come out well, and the larger idea is met, from the beginning of the project till the end. In between, those struggles are always there, and between the consultants, between the structure, to get our ideas to be put out, it is always a conversation.

Another project that we recently finished in the South of Bengaluru, is a small plot which has three large trees within it. We retained those trees even though the clients’ father did not want to. We wanted to add even larger trees once the project is done. The whole house then revolves around the concept of having three trees. All the bedrooms and the living room open to those trees. While we were doing the living room, it had a wooden deck in front of it, where the three trees are. These two decks are a part of the living and dining, so the dining opens out to that deck and the living opens up to the deck. These decks happened at the end of the construction, almost the finishing part. Till then, for one to one-and-a-half years, the client has seen only a small portion of the kitchen, and a small dining area and the living area and the moment the deck is done, they feel that the whole house has a large expanse, which they might not have visualised initially, but once it is done, they see that happening. His son always says that ‘my house is like a resort’. Even though it is within a small property, and within an urban context, because we retained those trees, it is more porous and more open, in terms of the houses.

AA: Whenever we go, and look at those trees now, it feels happier that there is life surrounding it. They are quite happy now, when we went for their housewarming, they told us that we were right, that these trees are blessing us now. In an urban context as well, it becomes an additional accessible space for them. We try to have that idea in every project, which is in the city.

CONTEXT

<00:50:19>

AA: From our college till now, we have been following Charles Correa and B V Doshi’s – Sangath practice, as it fits into the Indian context in a tropical sense. Sri Lanka’s Geoffrey Bawa’s work has inspired us, looking at the tropics and blurring those boundaries in many ways. Especially Charles Correa’s practice where that model he has designed, the pavers and footpaths for the hawkers, and cities like New Bombay (Navi Mumbai). You can see his portfolio, and journey of work, and it is very vast, and many are unbuilt – the unbuilt projects are as interesting as what is seen. The consistency of work, from the Sabarmati Ashram to the Champalimaud Center for the Unknown, you can look at the transition, as an entire journey and from a common man’s perspective, as well. […] How to look at everyday projects and still try to stretch that little limit, go to your street, and into your neighbourhood, and try that entire network. From when you are walking from your house to that temple, that entire journey, and how you want it to be.

In that way, we look at these practices as a role model for us.

Images and Drawings: © and courtesy; A Threshold

Filming: VCams

Editing: Gasper D’souza, White Brick Post Studio

PRAXIS is editorially positioned as a survey of contemporary practices in India, with a particular emphasis on the principles of practice, the structure of its processes, and the challenges it is rooted in. The focus is on firms whose span of work has committed to advancing specific alignments and has matured, over the course of the last decade. Through discussions on the different trajectories that the featured practices have adopted, the intent is to foreground a larger conversation on how the model of a studio is evolving in the context of India. It aims to unpack the contents, systems that organise the thinking in a practice.

The third phase of PRAXIS focuses on experimental vectors of practice and explorative models that support thought-provoking ideas and architectural processes.

Praxis is an editorial project by Matter in partnership with Şişecam Flat Glass.