A Srivathsan

A Recorded Lecture from FRAME Conclave 2019: Modern Heritage

In this lecture, A Srivathsan presents his view on the construction of Hindu Temples, and raises pertinent questions about the orientation of contemporary and modern architecture within this discourse. Using examples of temples built by young practitioners as a prism, he draws distinctions and similarities between what the sacred is and what is modern.

Edited Transcript

I would like to contribute to this conversation from the aspect of Constructing the Sacred. In particular, the Hindu temples, and what that tells us about the practice and discourse of Modern architecture in India.

For this presentation, I have considered temples only built by architects. Of course, there are a large number of temples that are not built by architects. Well, by ‘Stapatis’ in the informal way itself – self-built, community-built, and each one of them is a fascinating story and something that deserves full attention themselves. On the left is the popular temple, and forms the cover of the new book (referring to image 02). Actually, the book is published. It is co-edited with a friend, Annapurna Garimella, who is here. In this book, I have an essay where I have focused primarily on temples designed by architects.

When I started this inquiry which is not just limited to the book, but I have been looking at it for some time now, I was imagining a kind of conversation of a snake with two heads joined as if it has one, actually looking at each other; and one is the sacred head and another is the architecture head. And the sacred head is asking the architecture head, ‘What kind of architecture is better suited for architectural experience: the traditional or the modern?’ And I was imagining the architecture head asking the sacred head, ‘What are you as you are? Are you an ontological, given and unchangeable, or are you socially constructed, which means, I could experience and embody it in different forms that are particular to different historic situations?’ I thought that would be a very enriching conversation, which I would discover in looking at projects.

So, today I am taking about eight projects – four senior practitioners, and four young practices. And basically, at the end of the presentation or at the end of my inquiry, I realised that it was not such an enriching conversation because the views about both what the sacred and what architecture can do, sort of persistently remained the same. And the reason for choosing the sacred or the religious to look into modern is because that is where the modern is very sharply defined. There is no ambiguity about it, and that is quite instructive and I thought that would enrich our conversations here.

I am going to first quickly go through the series of projects. I am not going to dwell on the project. I will sort of annotate the projects but what is important is what these projects say. I have also extensively interviewed the architects who have designed them, and built them, and I have also closely read the texts that have commented on them because it is an issue to be looked at, both in practice and as well as in theory. It cannot be settled in either one of them.

I begin my story. We could begin anywhere, but based on what is accessible to me, I begin here. So, this is the Birla Mandir (referring to image 03) in Delhi designed by Sris Chandra Chatterjee, a civil engineer from Bikaner, who got interested in architecture and started a school of architecture called the Chatterjee School of Architecture in Calcutta. We do not know much about the details of the school but he was strongly advocating Indian architecture and eclectic architecture, not only for religious buildings, but for all buildings. He was one of the strong supporters of a national style for architecture. And it is not that he was not aware of what was happening in the United States of America and Europe. He was quite aware of it.

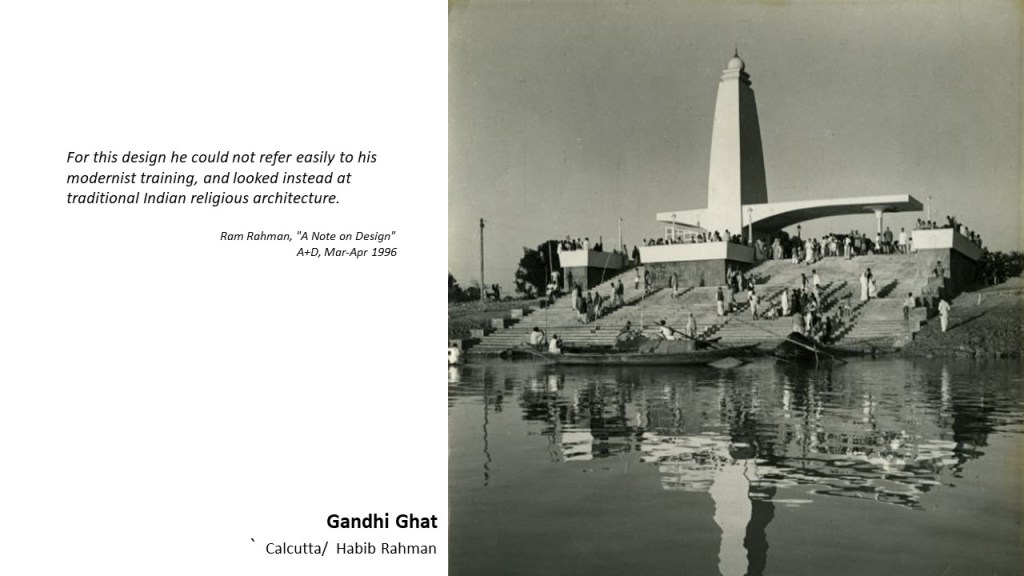

Opened in 1939 by Gandhi on the condition that this temple would be open to everyone, it was a ‘Sarvajanik’ temple. I mention this because I want to revisit this ‘Sarvajanik’ at the end. This we saw yesterday in a couple of presentations (referring to image 04) and particularly one sentence of Ram Rahman in the essay that he wrote caught my attention. That Habib Rahman, for all that we knew, was a very consistent, rigorous practitioner of modern and when it came to doing something commemorative, sacred in a difference, in a broader sense, he could not find something in the modern and had to dig deep into tradition. And that is something.

Again, this is Kanvinde’s project for ISKCON in Delhi (referring to image 05). Here again, the staunch modernist that he was, he could not possibly figure out a new language for designing a modern temple. And again, he had to go back into tradition in order to figure out a new modern. Of course, he explores the form (some of his sketches from the book (referring to images 06 and 07)). It is not surprising because the training that he had in Sir J.J. College of Architecture, where designing a temple was a standard exercise. I cannot think of any school today or in the last few decades, actually, though religion and temples are very important parts of the social, where anyone is paying attention to how to design it. I have not. Probably, I must start one soon.

This was another senior practitioner Narendra Dengle, based in Pune, who is an architect, writer, and translator, who extensively comments on even contemporary practice (referring to image 08). This is what you would call the most popular type of temple, which is a hybrid; a mix of style or elements, cast but in ferroconcrete, in this case (referring to image 09). Or his other temple for Ramakrishna Mission, again in Pune in Maharashtra, India (referring to image 10). Here, you would see Japanese, Italian roof styles, and Orissan styles, so it is a very eclectic thing which is popularly called as a hybrid architectural form. This is something that you would widely see.

Now I come to the four young practitioners here. This is Sameep Padora’s temple at Wadeshwar, widely photographed, often cited, and written about (referring to image 11). Completely built with basalt stone. Probably if there is a different way of defining the threshold or the entry, which is like a mandapa of a sort, and also having the shikhara open (referring to image 12), which is not so radical because some of this has been already attempted in some early temples because traditional temples are more or less closed. But actually those who designed the temples will tell you, there is a virtual opening, which connects the earth and sky. But this has been made more literal here.

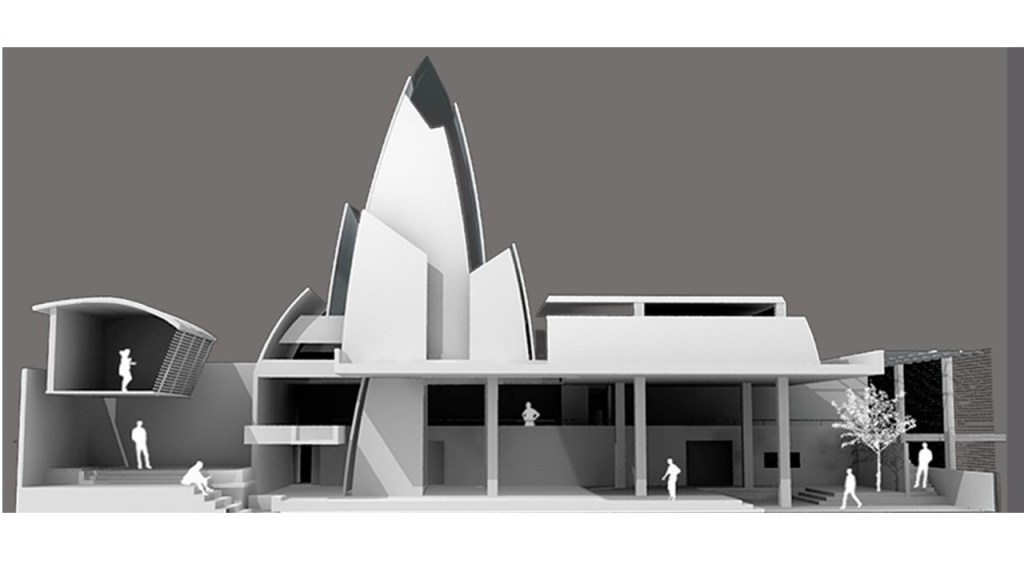

This is the Sai Temple in Bengaluru designed by Sanjay Mohe (referring to image 13). Variously interpreted by different commentators and actually, if you see (referring to image 14), he basically has taken the shikhara and just prised it open, held by glass so that the light comes in, but the spatial configuration inside is more or less the same. It is not very different. Of course, one would say that the modern temples are designed for congregation and not for personal worship, but I am sure Annapurna and others who have been doing studies, this innovation of moving from ‘darshan‘ to ‘congregation’ is already happening for a very long time. So, in a sense, it is not a very radical change. This is one of his sections (referring to image 15) and you could see the real estate compulsions where you have to have floors, and multi-level temples, but somehow try to connect the earth and sky in some kind of a contrived form.

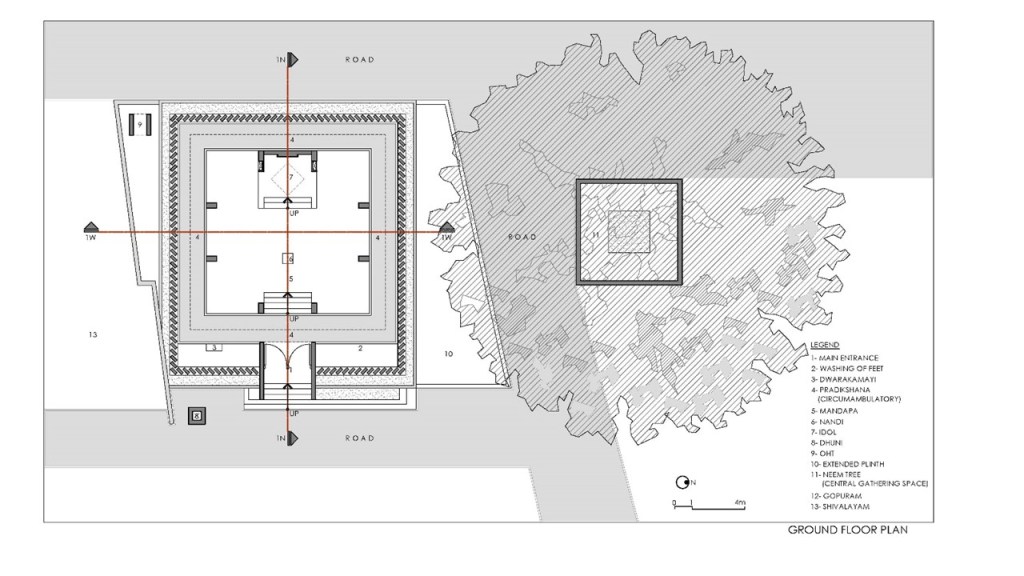

This a temple near Hyderabad by Hari Krishna of SEA Architects, made with bricks made by a German company (referring to image 16), of course, based in India. It is a special brick. What is interesting is to see the perforated boundaries (referring to image 17). And this is one important move, which again, I will revisit at the end because one of the key moves in defining or building a sacred space is the boundary. You split and sharply differentiate the sacred and the profane. And without that heavy, big, rough wall, you can not do that. But here he makes it perforated for a very important reason: he connects to the village square, which is adjacent to it, and allows the temple and the village space to interact with each other (referring to image 18). This is the compound wall (referring to image 19).

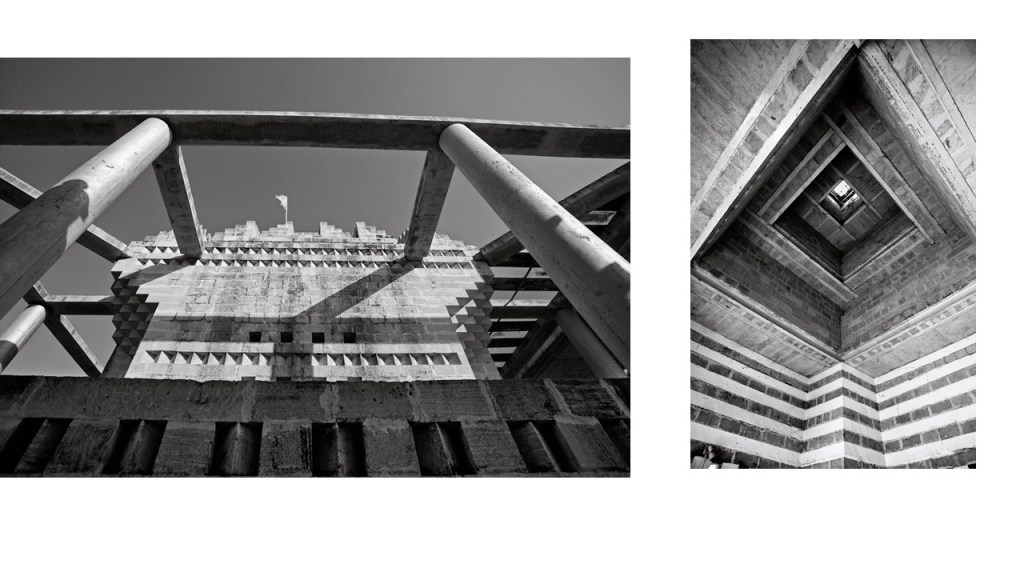

This is another temple by Space Matters in Barmer (referring to images 20 and 21). It is a very traditional form, but actually, the construction technique is different. We have yellow stones (Jaisalmer) held together by steel plates with slits so light comes in, in the morning and light peeps out in the evening. These are very detailed construction drawings of how this temple was constructed (referring to images 22 and 23).

This is a temple in Ahmedabad by JMA Design Collaborative, a young firm (referring to image 24). Lots of these interviews throw up some light in anecdotes and stories. I do not have time to share, but maybe one or two. Here for example, Mehul Bhatt, the principal architect of this temple, conceptualised something very traditional, ythe client said, ‘No, I need something contemporary’. So, all they did is they took the Shikhara, stripped it of its ornamentation, and cast it in concrete with slits of glass and that became contemporary.

This is Snehal Shah’s temple in Porbandar (referring to image 25). Of course, another interesting story here because the client asked, ‘Snehal, in traditional temples there are iconography, statues on the periphery and the external walls. Where are they?’ I believe this is what he told the client, ‘Please look very carefully at the shadow patterns, you could discover Rama and Krishna there.’ And I am told that the client was convinced. Here, the inside is stone and the outside is steel and glass; the parikrama. This is another view (referring to image 26).

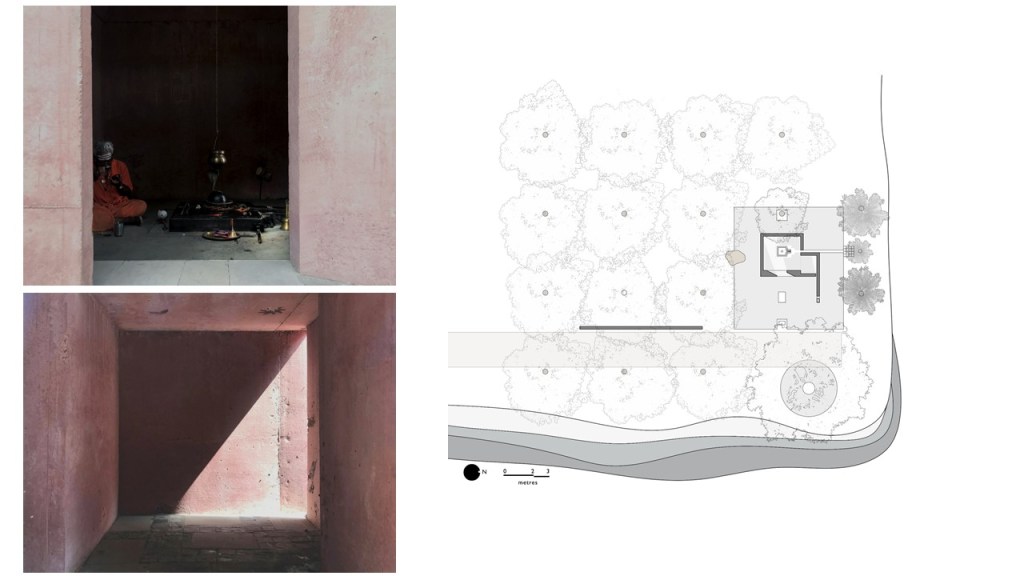

The last two projects. This is completely cast in coloured concrete, a small temple in a village near Pune by Karan Darda (referring to image 27). Here again, there is a very fascinating story of the conversation between the architect and client. And actually, I am told, that they went through various churches and mosques of recent times. And this is what they ended up with (referring to image 28).

The last of the project; this is the Maruti Mandir by Shailesh Devi in Nashik (referring to image 29). Except for the stark black stone and some chiselling of the traditional form, it is more or less like a regular temple.

Now I just come to the interviews, and the close reading of texts (referring to image 30). They are long interviews; I am just putting the key excerpts. What comes through in all these interviews and how all these architects look at what is appropriate to manifest a sacred experience is tradition. So, they cannot think no matter what they do repeatedly. Very interesting. For example, Amritha Ballal from Space Matters says that though traditional knowledge and design principles are not accessible, there is still no way one can gravitate away from traditional forms (referring to image 30). And similarly, it is the stance of all the architects. At the most, the idea of innovation comes in the form of a hybrid. And that is a point that we will again revisit at the end.

So, I looked at the books because I thought this was a very important type, an unbroken type, which was constructed for many centuries (referring to image 31). What does the book say? Including Peter’s new book, there is a very scanty reference to it. I do not complain because probably contemporary architecture is yet to be considered a worthwhile marker of design. Rahul Mehrotra makes a passing reference and he constructs it as a counter-modernity, which I disagree with, but nevertheless, it is an important point to engage with.

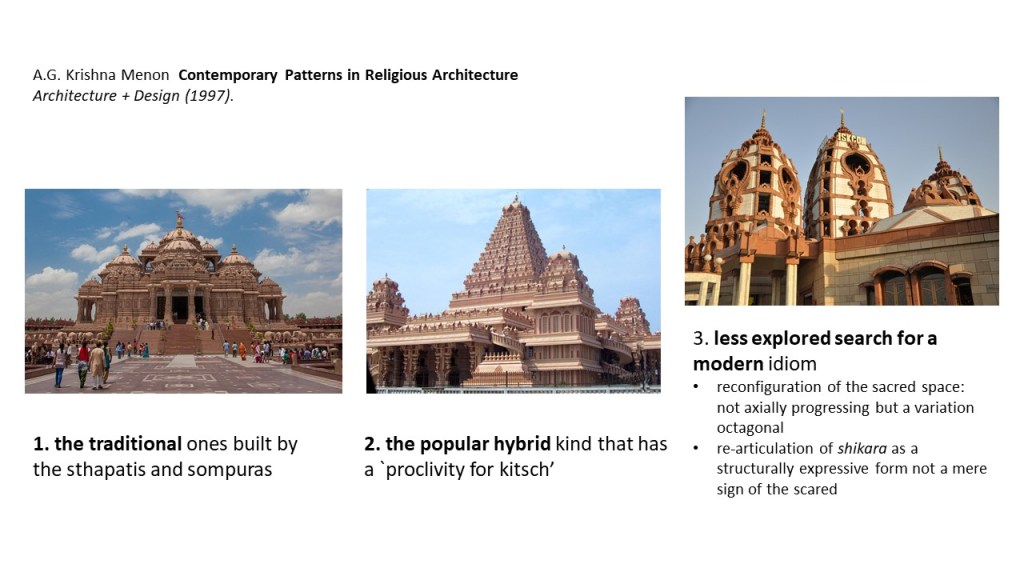

On the other hand, the kind of sacred architecture outside the Hindu religion, church in this case, mosque maybe, and synagogues too, is also an equally important thing. As Robert A M Stern would observe, today you cannot write the history of contemporary Western, European or American architecture without including a good number of religious buildings (referring to image 32). It is impossible to conceptualise contemporary histories without these buildings because these buildings mark and embody a substantial amount of creative and significant design development. Not that nothing has been written about it and I just take two papers here and I think because they are very important. One is A G K Menon’s paper often cited by anyone who is looking at religious architecture in India (referring to image 33). It is written in 1997. The other one is by IIT Kharagpur, by Arjun Mukerji and Sanghamitra Basu (referring to image 34).

What is important is the device in which they look at contemporary religious architecture and use the tool of categorisation. Now actually Menon has to be blamed for this because he introduced it and it is still stuck with us. So, he classifies most of the religious architecture into three categories (referring to image 33): the traditional, the popular hybrid, and the less explored modern idiom. It completely condemns the popular hybrid because he condemns it as kitsch. In fact, he has very weeping sentences about how Staptis have taken to concrete and all that. So, he laments about such hybrids while he says that the modern idiom is less explored and he holds Kanvinde’s temple as a great example. However, he does not flesh out what he means by that. But I interpret from his sentence that he actually says the spatial configuration is not the traditional, and hierarchical, and is rather octagonal, which is a very typical architectural geometrical obsession, and the Shikhara is far more expressive than simply being symbolic. Mukerji and Basu also actually try to look at it from these terms (referring to image 34), but they come up with a very ironic term called ‘the post-modern temple’. I never understood, both the term post-modern in Indian condition as well as particularly, post-modern. If hybrids are not postmodern and if many of the moderns are actually a mix of many traditional elements, so what is distinctively post-modern about it?

Of course, in both cases, there is a certain preference. Each author thinks it should be the way forward. But I found the most radical of interpretations of what is sacred in architecture in Adam Hardy’s work where he says that the temple architecture is more like a ‘svayambhu‘. It comes out of it as an internal logic. It is a very emanative process and there is an ingenuity to it. Now, he recommends that an architect can innovate designs following an internal logic. What matters is the process of production. This probably should have given the intellectual framework or an inspiration for designers to not really worry about either being traditional or modern, or contemporary, or whatever categories, but actually go with the internal logic of the production of that space. But, unfortunately, not only it has happened but Adam Hardy himself at the end of the paper says, ‘Okay, man, all set. But I like this. Don’t do modern, everything else is fine.’ (sic) And he gives a reason of why modern is not appropriate for religious architecture. He says it is more of a creative personhood, innovation is a market myth and there is intrinsically nothing meritorious. So, it is a little disappointment to an otherwise very radical proposition (referring to image 35).

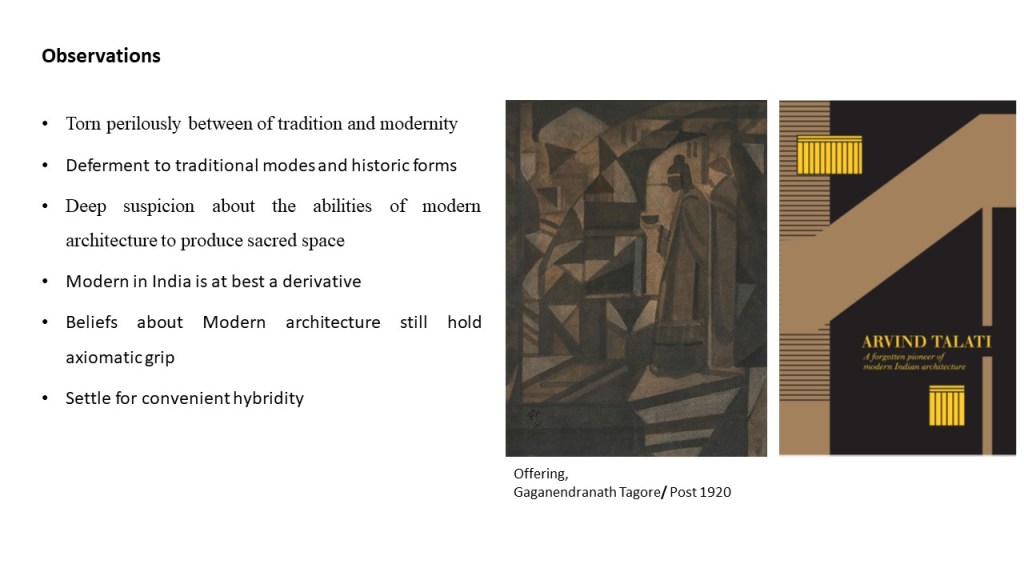

In this context, I just want to make some observations and comments before I move to what is happening elsewhere. Well, contemporary architecture in India has a bewildering variety of responses to changing social and economic conditions in the country. It has embraced with confidence, tradition, the modern, and its architectural process and subsequent developments, refusing to be contained through categories such as the Western Modernist and so on and so forth. The wide range of architecture over many decades in India has been moving on its own terms. However, it appears that the same cannot be said about religious architecture, particularly that of the Hindu temples. Both production and discourse are torn perilously between the binary of tradition and modernity. A deep suspicion about the abilities and appropriateness of modern architecture to produce Hindu temples seems to prevail even as its technologies, expertise, and sometimes spatial configurations are implicated in the continuity of the tradition.

Practitioners exhibit anxieties about authenticity and deferment to the traditional mode of design. Religious structures cannot be imagined outside historic forms and spatial layouts. The suspicion about contemporary architecture runs deep. The problem to me seems two-fold: First, as Partha Mitter convincingly demonstrates in the case of art, which in my mind applies to architecture as well, certain beliefs of what modernism still hold an axiomatic grip of many minds. Any production of modern art or architecture beyond Europe and the United States is at best a derivative exercise. And as William Archer, the art historian humiliatingly dismissed, cannot be a genuine item unless the society has absorbed it into the bloodstream. Here he uses, the case example of Gaganendranath Tagore’s paintings of the cubist (referring to image 36). Most of them look at it as an imitation and William Archer actually dismisses it as imitation, but Partha Mitter convinces, even including Gaganendranath’s own words: They do not really share the same kind of ideas of abstraction as the other cubists did. But to them, it was a tool to do better and more of what they were already doing. So, there is a visual resemblance, but that does not mean anything other than that. The tool was used for better representation, engagement, and exploration.

The other image on the right-hand side is of my own work on a lesser-known architect Arvind Talati (referring to image 36). I call him the forgotten pioneer. He worked with Le Corbusier between 1954 and 1957. After B V Doshi left Corbusier, he did more than a hundred drawings, which is what the Foundation archives list, and has done some very important projects; part of many important projects like the Ronchamp (referring to images 37 and 38), the Tower of Shadows, and so on. So, for this cover, I particularly chose this image because in 1969, when Talati built the Industrial Housing in Ahmedabad, this staircase resembled Corbusier’s Pessac housing in 1929. And people dismissed it as imitation, but actually what Talati was doing in a very Asian way was paying homage and taking an iconic staircase to do it. Otherwise, the plan form, the way it engages the street, and the way it climatically responds has nothing to do with Corbusier’s housing.

So, the way in which things have been written, discussed and, interpreted, is problematic to me. And that is also a problem of what we are now facing that the Modern is yet to become ours. It is always a derivative, an imitation and there is some kind of resistance to that. I will quickly go through what happened elsewhere, just to contrast it.

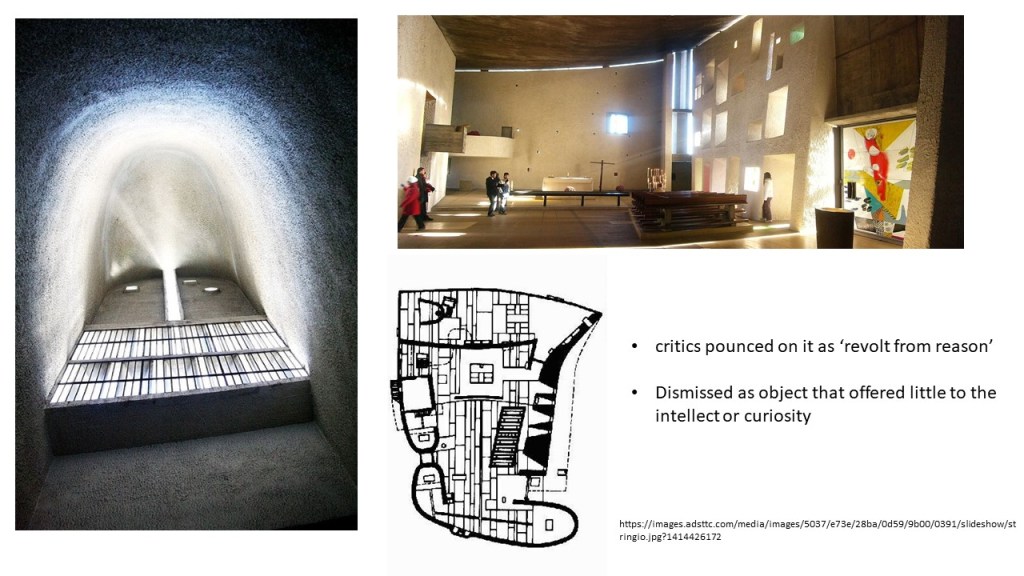

Of course, this is a well-known building and when this was built (referring to images 37 and 38), not everyone thought it was a great piece of architecture, but the initial reactions were that it was a ‘revolt from reason’, somebody said, and it was dismissed because it offered nothing to the intellect and curiosity. But strange the history is, and suddenly it becomes the most canonical and the most revered architecture.

So, just to extend that thing there is suspicion that modern architecture produces sacred experience was there even in the case of churches. Because it was seen as being very functional, and the church was seen as a prayer barn, et cetera (referring to image 39). But a significant question that was posed was whether modern had the capacity to bear that experience or not. People thought that modern architecture had nothing to do with sacred and religious experience, but this wonderful book – ‘ The Religious Imagination in Modern and Contemporary Architecture: A Reader‘, (referring to image 39) and you will be surprised how modern architects, including Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and others who we thought had nothing to do with sacred or religious, have not extinguished this reflection of what is religion and sacred and how it impacts on their architecture production and this reader is a very useful collection in that aspect.

But of course, the architects too came up with their own defence and explanation about their work and why it should be taken seriously (referring to image 40). Of course, Corbusier’s popularising of the term ‘ineffable space’ in his own way. He said he is the inventor of this term, which he is not. But this notion of ineffable space, that space and architecture and form could sound with the inner chord, release an immense amount of aesthetic emotion, be evocative, etc was a useful way and a possible way to make the sacred experience accessible and it is not necessarily to be done only through signs and symbols. There were other German architects, particularly Rudolf Schwarz‘s engagement with the idea of monumentality and light. This is again another German architect (referring to image 41, left).

They were also kind of pushing this forward that modern architecture is absolutely capable, like tradition or any other architecture, of making sacred experience accessible. The idea of the ineffable has been further expanded with this new book (Constructing the Ineffable: Contemporary Sacred Architecture) (referring to image 42) by Karla Britton that will tell us that there are many techniques, for example, the creative use of light, spatial parallax, and so on and so forth to manifest that.

I am not getting into other religious architectural forms and designs, but that is an example of a mosque from Dhaka, Marina Tabassum‘s, which you would be familiar with (referring to image 42).

This (Saint John’s Abbey Church: Marcel Breuer and the Creation of a Modern Sacred Space) (referring to image 43) is an important book because I have been talking more from an architect’s point of view , but this is another book that talks about Marcel Breuer’s design for the Church in Minnesota. What is important is how a biography of a building could actually offer more insight, which Ranjit Hoskote was making reference to, about the biographical context in which decisions were made, contingencies, and other kinds of environments in which decisions are made are absolutely necessary to understand. This book has a very interesting chapter of a conversation between Marcel Breuer and the Benedictine monks, who had commissioned it. So, Marcel Breuer had not done any religious architecture, but he was commissioned. So he was worried as to why he was commissioned. He asked the monks why he was chosen because there were other big, wonderful names in the U S at the time. The monks actually told him that they had studied his architecture, and they were confident that his approach would give them a wonderful, sacred space and a great monument to Christ. And they told Marcel Breuer that they wanted concrete. So, they were very specific that they needed concrete to evoke these experiences.

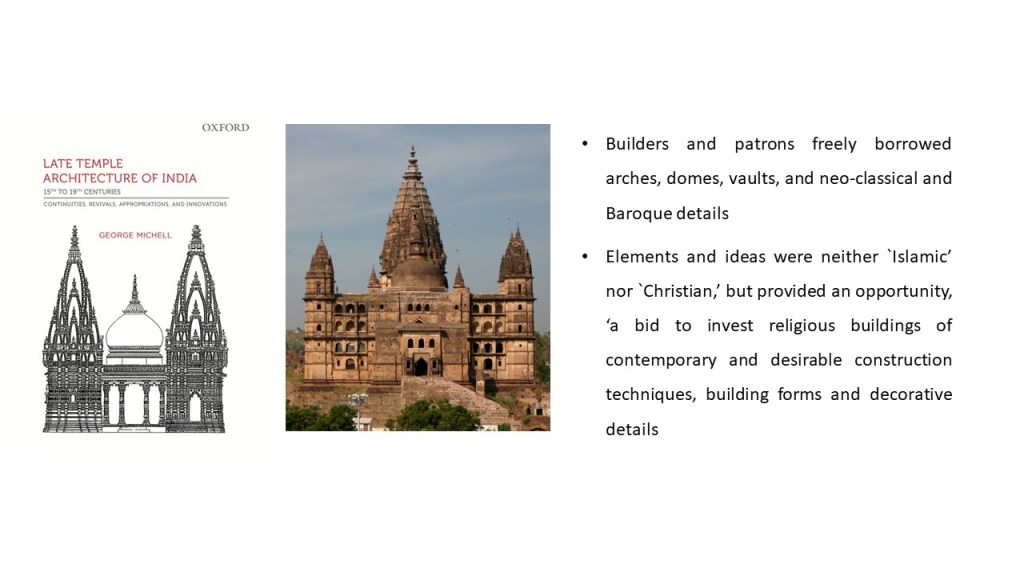

One should not think that these were possibilities of architecture only in the non-Hindu sphere. But actually, if you read the recent book (Late Temple Architecture of India) by George Mitchell (referring to image 44) on the temples built between the fifteenth and nineteenth centuries. Mitchell makes an important observation. He says temples are constantly a thing of innovation, exploration, and engagement. There was no distinction between Christian or Islamic features. They adopted it and they were always thinking they were building something contemporary and whatever was required to push and explore new forms of engagement, they did try.

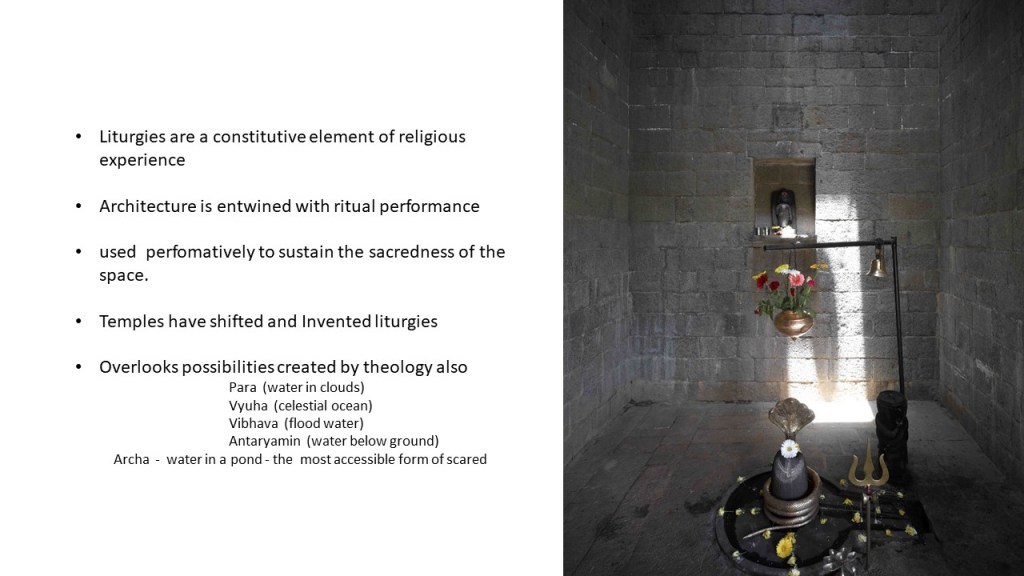

Another argument that normally comes up in such discussions is that Hinduism is more liturgically different and that other religions have different kinds of liturgical demands and hence one cannot compare with them (referring to image 45). Absolutely right; that the liturgies are different, but even in church architecture, many would say the Eucharist comes first. So, the ritual is absolutely entwined with architecture. There is no separation of it. But to think that the liturgies are unchangeable and it was not invented is not true.

The liturgies are constitutive elements of religious experiences, and there are many stories in which many incidents we can know, even in contemporary temples. For example, those who are familiar with the Vaishnavism theology would know the two agama traditions of Pancharatra and Vaikhanasa. There are many temples which do not have a Vaikhanasa priests, but actually shift to another agamic tradition, which is blasphemy; you have to re-consecrate the entire temple. But people have invented and adapted to multiple things. And even from a theological sense, I am just taking one example, which is the Vaishnavite way of how a religious experience can be accessed. So, the Vaishnavites believe that there are five ways in which religious experience manifests or the sacred manifests in this world or the cosmos: The Para, Vyuha, Vibhava, and Antaryamin (referring to image 46). I do not want to go into these terms, but using the analogy of water, the traditional scholars have explained. So, there are different forms, like water, the water below ground, which is Antaryamin is of no use, they say. The Vibhava as is the avatar is just like the water in the flood. It is too of no use to you. And the Para, which is the cosmic, which is in the cloud, is not accessible at all. So, what they say is, that Archa is the most accessible of sacred forms and here Archa does not necessarily mean only idols. It means any concrete manifestation is what is more desirable and that concrete manifestation can happen in multiple ways.

I want to end this presentation with a note of hope and expectation. In recent times through their practice, a few young architects have challenged the burden imposed on them to express regional rootedness or to seek traditional forms as a means of embodying a sense of place or purpose. They do not share such architectural anxieties anymore. The buildings get rooted in the place, through their performance. Their works ask if the sacred in sacred architecture as Karsten Harries explains, is an experience of incarnation of spirit and matter, it should be possible to achieve it in multiple ways. Reconceptualisation has begun to set in the form of social and political concerns. Kajri Jain and Gail Omvedt point out how canonical temples are restrictive and exclusive. Many temples exclude Dalits and women and are not truly Sarvajanik: a place for all people. Containing and erasing of Dalits and gender politics permeates; the challenge is how to make the temple genuinely public.

As Kajri Jain would point out, some of the new popular sacred spaces have taken to iconic and exhibitory modes to formulate the Sarvajanik and provide a range of social actors a way of accessing sacred experience. The beginnings of such possibilities can be seen in this Sai Temple in Vennached (referring to image 47). In a traditional temple, the boundary wall is severe. Well, their intention is to insulate the sacred from impurity. Contrastingly in Vennached here, the boundary wall is a brake tracery that is porous. While old and young claim the platform around the tree, women and children use the plinth and the interior extensively.

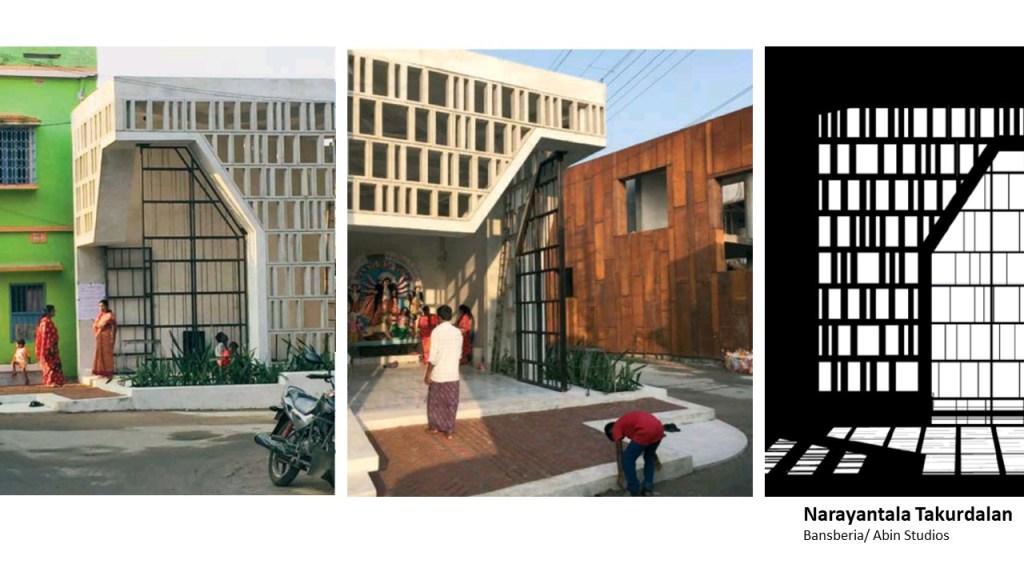

Narayantala Thakurdalan temple in Kolkata by Abin Design Studio sitting in a nook (referring to image 48), a very small, tight corner in Bengal, looks at religious structures as part of an affordable social infrastructure to provide dignity. If you were to compare it with the roadside shrines, which as one of the anthropologists called ‘the gods of the squatters are also squatting gods’, made out of cheap materials and occupies the public parts and so on. So, the challenge is to make a certain kind of temple that is easily accessible with greater dignity and view it as a part of an affordable social infrastructure. And certain architects are already moving in that direction.

Thank you. ♦

Dr A Srivathsan is an architectural scholar with more than twenty-five years of cumulative experience in teaching, architectural and developmental research and professional practice. Some of his major research projects include: Hampi -The Indian Digital Heritage Research Project (as part of larger team), Department of Science and Technology Initiative; Re-envisioning the City, Research funded under Indo-Dutch Program on Alternatives in Development; Mega Cities Project. His publications include books and papers in reputed journals.

He is the Center Head and Principal Researcher of CAU. Srivathsan served as the Academic Director of CEPT University for five years where he worked closely with the Deans and the Heads of Academic Offices to refine academic policies and practices, to strengthen academic rigor and deepen the culture of research at CEPT University.

Prior to that, he has been associated with The Hindu as Senior Deputy Editor while serving as Adjunct faculty at Asian College of Journalism, and at the School of Architecture and Planning, Anna University, both in Chennai. Prior to this, he was Assistant Professor at Anna University, Chennai for ten years. He has also been a practicing architect for eight years. He is an active member of various institutional bodies, contributing to the development of new academic programs and introducing new courses.

Dr Srivathsan holds a PhD from Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) along with a Master’s degree in Urban Design, School of Planning and Architecture, New Delhi.

FRAME is an independent, biennial professional conclave on contemporary architecture in India curated by Matter and organised in partnership with H & R Johnson (India) and Takshila Educational Society. The intent of the conclave is to provoke thought on issues that are pertinent to pedagogy and practice of architecture in India. The first edition was organised on 16th, 17th and 18th August 2019.

Organisation and Curation: MATTER

Supported by: H & R Johnson (India) and Takshila Educational Society