Pankaj Vir Gupta

A Recorded Lecture from FRAME Conclave 2019: Modern Heritage

In this lecture, Pankaj Vir Gupta discusses the conception of Sri Aurobindo Ashram in Pondicherry. Gupta delves into the architectural history of this structure, highlighting its pioneering use of concrete in India. He recounts his personal experiences at Golconde, sharing vivid details about the architecture and its unique features.

Edited Transcript

It is a particular privilege to be presenting a project with which we started our practice in 2003 and in the office archives, this is project 001 (referring to image 01). So, this morning to wake everyone up, I think it is important to understand why we are here to talk about this building and I will try and make it as energizing for you as possible.

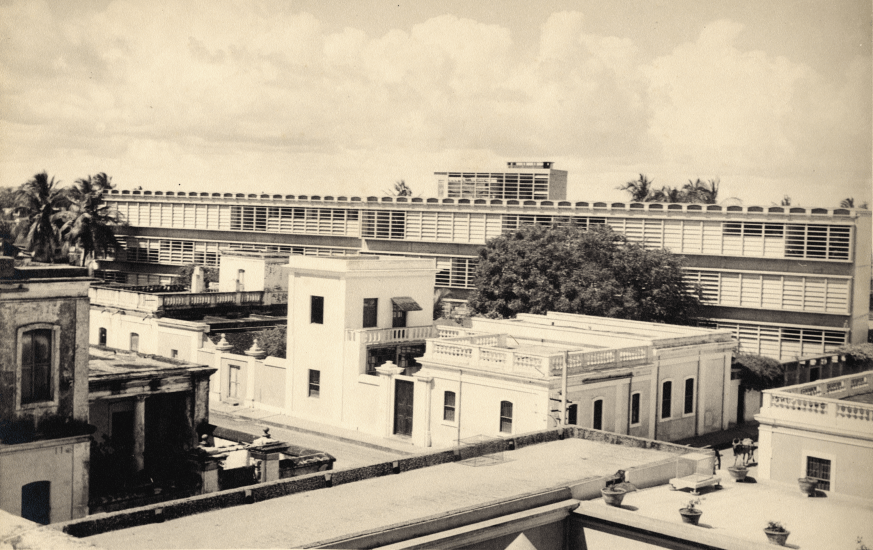

My name is Pankaj Vir Gupta, and with my partner, Christine Mueller, I run a practice in New Delhi called Vir-Mueller Architects. I am also a professor of architecture at the University of Virginia, where I run what is called the Yamuna River Project, a multi-disciplinary research project, looking at ecology and urbanity in the megacities of the world. But to go back to how we started our practice, I was leading a study abroad program with some students from the University of Texas and we happened to be visiting Pondicherry, to look at the urban fabric of the city (referring to image 02), and we came across this extraordinary building (referring to image 02) and it was a surprise to me personally, because in several years of architectural education and research, I had never come across this building in any writing or any publication, at least not in the curricular work that we had been exposed to in our education.

And then, as I started to delve into a wider search by this time, in 2003-2004, I realized that this building had been completely missed by historians who had documented Indian contemporary work or Indian modern architecture. So, Christine and I were very fortunate to receive support from the Graham Foundation in Chicago, to go and live in Pondicherry and study this building and actually stay in this building and for the first time have access to all the archival notes and footage that was there. So, what I am basically going to do is tell you a story of how this building came to be.

Sri Aurobindo was an Indian freedom fighter, philosopher, thinker, who had been accused by the British of sedition and so had abandoned British India and with a small core group of followers, had set up domicile in Pondicherry, which at that point was a French colony, to escape the reach of the British empire. He was an extraordinarily gifted student who was schooled in England at St. Paul’s and then at Cambridge. And so had attracted around him with his prolific writings and general appeal to the philosophically minded in those troubled times, a group of very accomplished international thinkers, and historians, cultural theorists, who all had gathered around Pondicherry and started occupying pieces of what was then the French port town. This is an old site plan that we found in the archives (referring to image 03).

The problem with this was that the French started to doubt the concentration of these people in the midst of their colony, and then proposed to Sri Aurobindo that he start to evict his followers and move closer to what was then called Tamil Town, the kind of indigenous settlement, closer to the canal that divided the old settlement of Pondicherry from the French town. And so, this first site plan shows you the canal and it shows you the planned grid of the French quarter, and this plot of land labeled A was really a plot of land that became available for the burgeoning Ashram to set up their own domicile (referring to image 03).

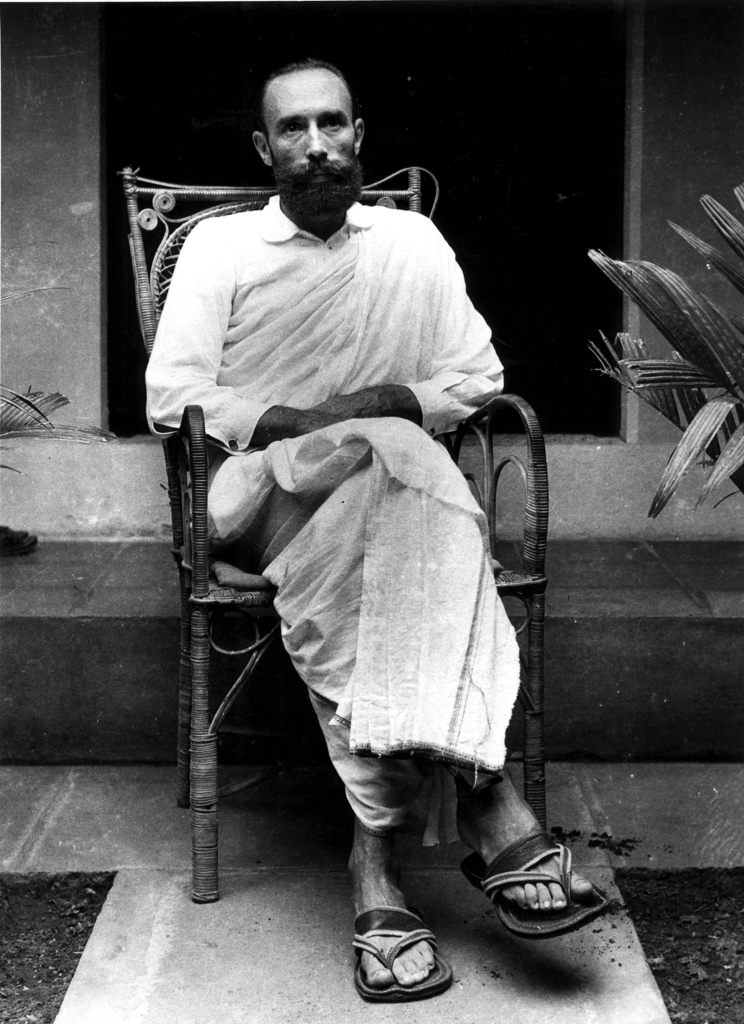

At that point, the affairs of Sri Aurobindo Ashram were handled by a French gentleman named Phillip Santee Lair (referring to image 04), Pavitra was his name, named by Sri Aurobindo, and interestingly enough, in the late thirties, he was already aware of the work of Frank Lloyd Wright and the kind of organicism that was being practiced in Japan at the Imperial Hotel project and he wrote a letter and reached out to his old friend, Antonin Raymond, Czech- French architect who was working with Frank Lloyd Wright on the Imperial Hotel asking him, if he would be interested in coming to visit a site in Pondicherry and so this also tells you the story of that culture at the time, both the mother, Mirra Alfassa, who was Sri Aurobindo’s spiritual companion, also leading the Ashram and Phillip Santee Lair, Pavitra, were not looking to just do another building in the French colonial province. They were looking to really introduce a catalyst, a kind of avant-garde piece of work that would also energize the Ashram.

This is an old portrait of George Nakashima (referring to image 05), the woodworker, which we found in the archives. George Nakashima was a young intern in Japan. He had graduated from the MIT in Boston. He had made his way to his ancestral land of Japan, although he was born and raised in the United States in Washington, and he had found employment with Antonin Raymond and after Antonin Raymond made his initial visit to Pondicherry, he deputed George Nakashima to go and live in Pondicherry and become the project architect for this Ashram and coincidentally, this is now 1939, so the World War has broken out and this has affected shipping and traffic across countries- not to mention the movement of material and goods. So, George Nakashima essentially was deployed to go and base himself in Pondicherry for the duration of the project.

In this photograph (referring to image 06), the second lady from the left, is the daughter of the American President, Woodrow Wilson. So, you can see, she was a resident of the Ashram, she was a devotee of Sri Aurobindo, on her right, holding the baby in her arms is Mona Pinto, another early devotee who had come from England, with her friend Udar Pinto, aeronautical engineer, also a follower. I am showing this to tell you the story of how this building came to be. These characters are all extremely important in the architectural conception. This was not a building designed autonomously in an office by a team of architects and draftsmen. This was a building that distilled the cultural polymath values of this enterprise, and that is what is interesting.

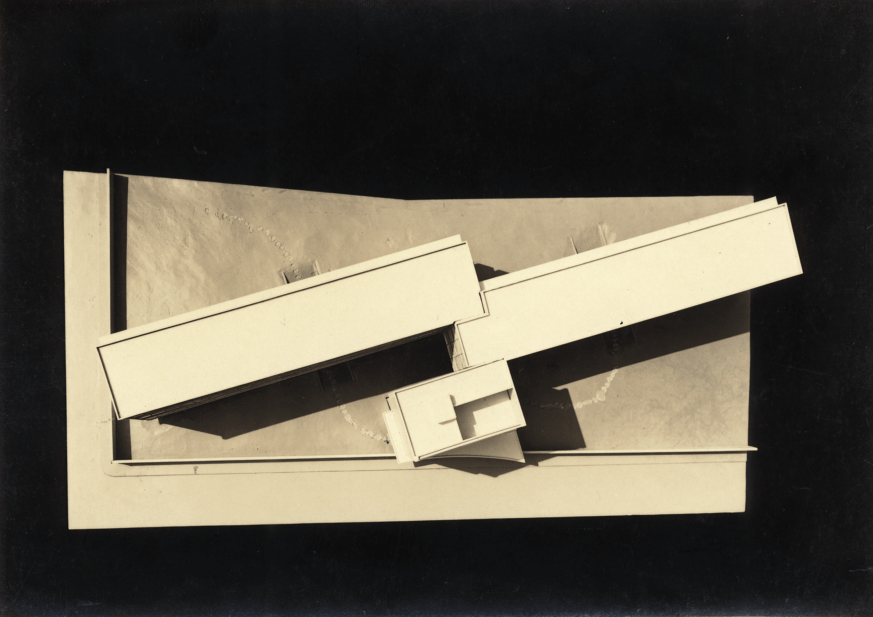

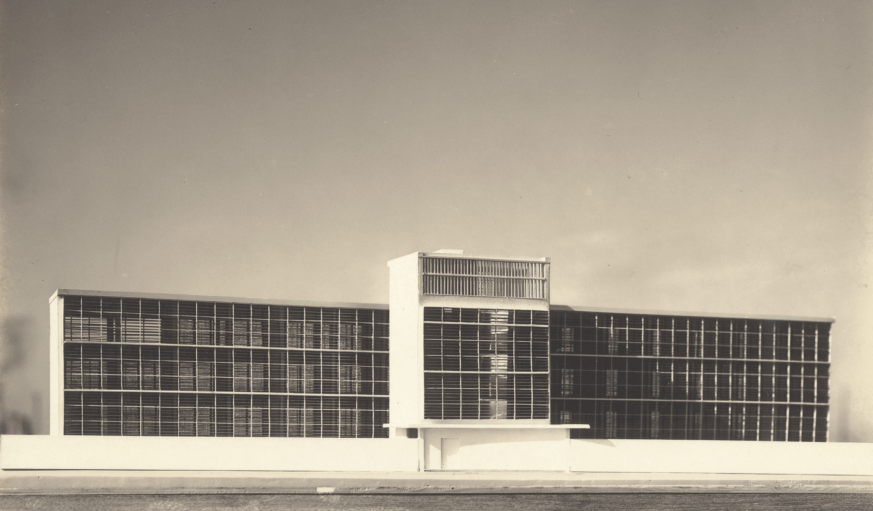

At that point in Japan with the war breaking out, Antonin Raymond’s office did some very basic schematic design iterations. This is an early model photograph of that schematic design (referring to image 07) showing how on a very narrow plot, the building was oriented north-south to take advantage of the prevailing breeze with a node for circulation. Another early model photograph (referring to image 08). All of this material was in the Ashram archives and had never been opened since 1945. So, when Christine and I went to live there and gained the trust of the Ashram, piece by piece, these fragments of information were revealed.

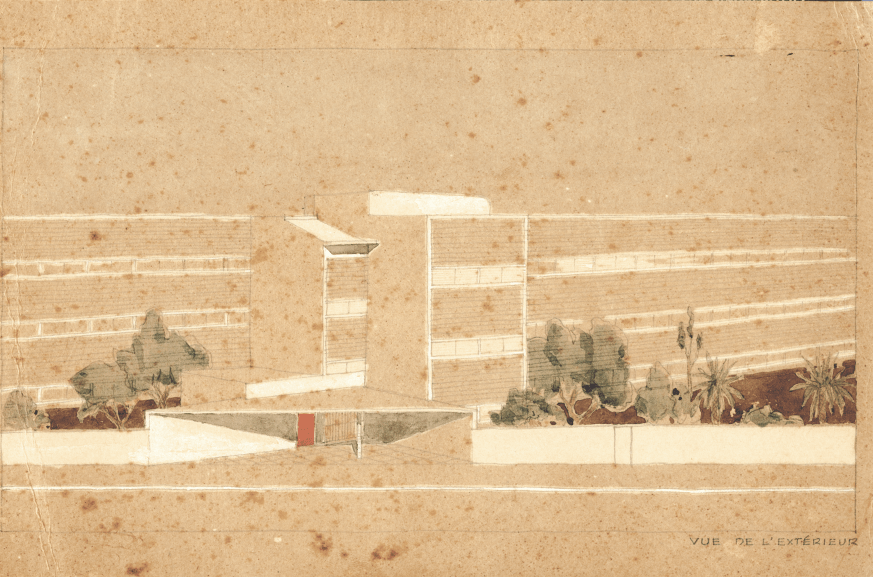

This is a very beautiful early watercolour done in Japan by Antonin Raymond, showing the conception of this new building (referring to image 09) and we found a quote from a letter he wrote to Sri Aurobindo and the Mother saying that this building had to represent principles and not an aesthetic portrayal that might be perceived as cartoonish or caricature of that which had already been, it had to reflect abstract principles dealing with climate and material and structure. So already, the notion of a tectonic expression, a material expression was coming alive in the way, because, for 1937, this is a pretty radical drawing.

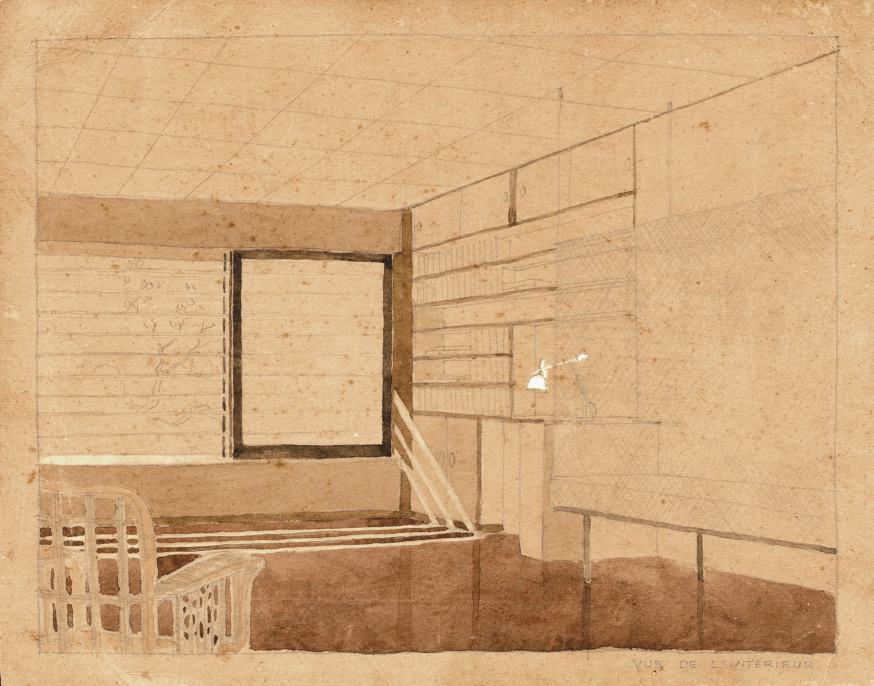

Another photograph of the model (referring to image 10) and what they proposed was a system of louvers that would be cast in place in concrete that would allow the breeze and the light to temper the heat of Pondicherry in the monsoon and in the summer. Interestingly at this point, concrete had never been poured in any building in India. Another perspective view done by Raymond of what the interior of one of these rooms for the Ashram would be (referring to image 11).

Here is an early photograph where you see George Nakashima in the sunglasses with a bunch of the early devotees (referring to image 12). At this point, as the schematic design is complete, Nakashima arrives in Pondicherry and starts working on a set of construction drawings. The Mother informs Antonin Raymond in a letter that Sri Aurobindo had decided that no construction company would be allowed to build this building. They did not want a commercial enterprise. They did not want a contractor, to build this building. Raymond wrote a letter back asking, “Well, how else do you imagine we are going to pour concrete for the first time in India?”. And the Mother answered their letter with a missive saying- that we have devotees. They are poets and philosophers and historians and cultural theorists, and they will pour the concrete. This is the original band of the construction workers who were going to assist George Nakashima to build this building (referring to image 12). So again, you can understand that there is a utopian sensibility about the way this building would come to be.

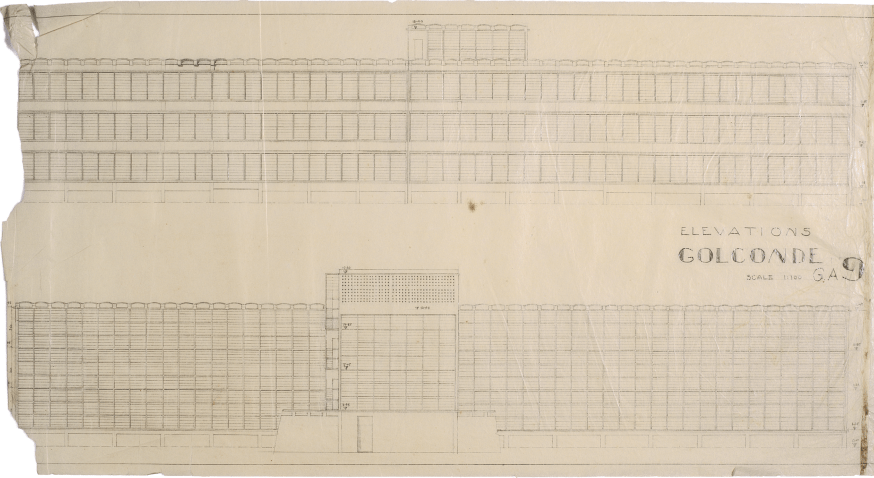

[10:30] These are the early original drawings that we found in the Ashram (referring to image 13), all a fairly fragile ink on vellum and these were drawn in the Tokyo office sent with Nakashima to Pondicherry, but very preliminary, just showing the orientation of the rooms. This was a dormitory for the members of the ashram, and the circulation core. You can see the early elevations (referring to image 14).

And the landscape that Christine and I found outside of Pondicherry (referring to image 15) has actually remained largely unchanged in the 75-80 years since this building was conceived. So, the salt flats, the salt pans (referring to image 16), very basic forms. And this was important to us as we began to understand- how would you begin to deploy a material and a structural technology that had never been used in this place.

We found an original drawing (referring to image 18), showing how they propose to build a full-scale prototype, to understand how concrete might react in this context, in this climate- how it might be poured, how the mixes might be improved. India did not, at that point, manufacture either cement or steel. With the war going on, the cement had to be imported from France and the steel from Japan and this was a very expensive proposition. The Ashram at that point- we found the original bill of quantities and the building actually was built for that money, the original, stipulated budget was one lakh and one hundred rupees for the entire construction of Golconde, one lakh and one hundred.

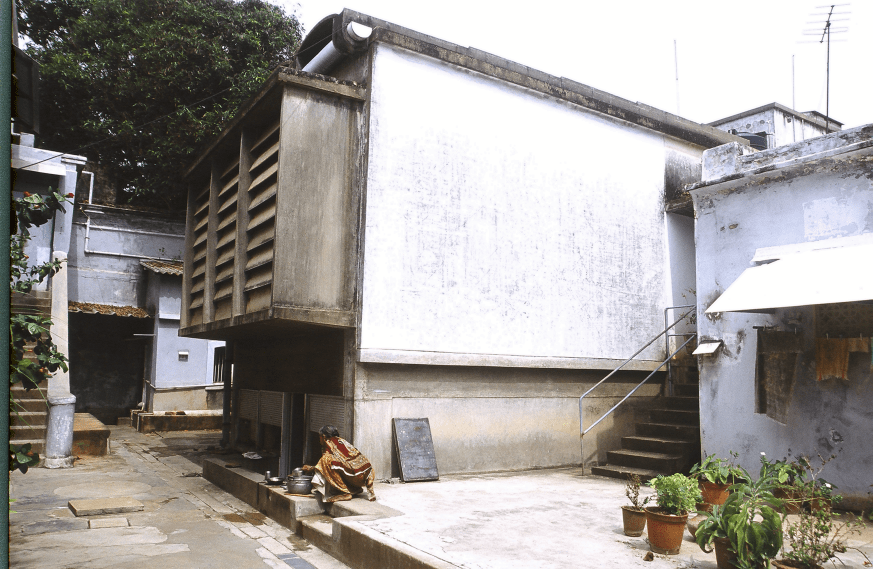

This was the model house (referring to image 19) and it took us weeks to find it. It is actually behind a small temple door in the heart of Pondicherry and that temple door is guarded by Lakshmi, the temple elephant. We were told it is somewhere there, we kept walking around and finally, one day the elephant was not there and we saw the door. So, we walked in and this was the full-scale prototype and actually an original devotee of the Ashram has lived here since 1941. That is the interior, it is the kadappa stone floor (referring to image 20). The difference was these louvers were made of zinc. At that point, the first prototypes were made of zinc, hand beaten zinc. You can see the hardware made out of teak. That is the interior (referring to image 21), and that is the first concrete pour in India, you can see the exposed concrete on the roof. This was finished in 1939-1940. All the furniture was fabricated by George Nakashima. This is the first time he is actually working as a woodworker because he is trained as an architect.

That model house led to the development of these sections (referring to image 22). The idea that the building would float over this excavated basement, the breezeway would become a lounge and then these three floors of rooms, would be terraced above.

Construction began. Concrete began to be poured and Nakashima writes in his journal, which we found- his original journal in the archives of the Ashram. He writes, “This is a beastly wood, this mango wood that I am being given to do the shuttering, the form work for this building. It keeps exploding and bursting, the concrete collapses. I do not know what to do”, and he is addressing this missive to the Mother who is not an architect, who is not his patron in Japan, but actually the client, and the Mother writes back in her penmanship on that diary, “Do not despair, use teak”. And again, for Christine and me, starting our practice, it was so extraordinary to see this documentation, this kind of back and forth between patron, client, and architect. Architect, struggling to develop the language and the vocabulary, patron encouraging and actually saying- no use a much more expensive wood, it is more strong than the mango wood.

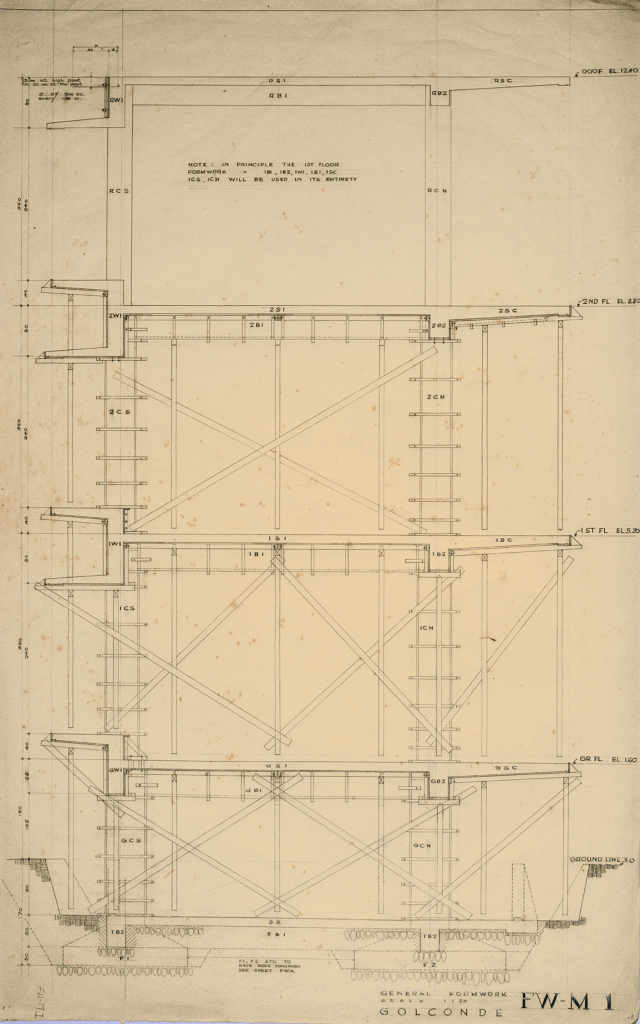

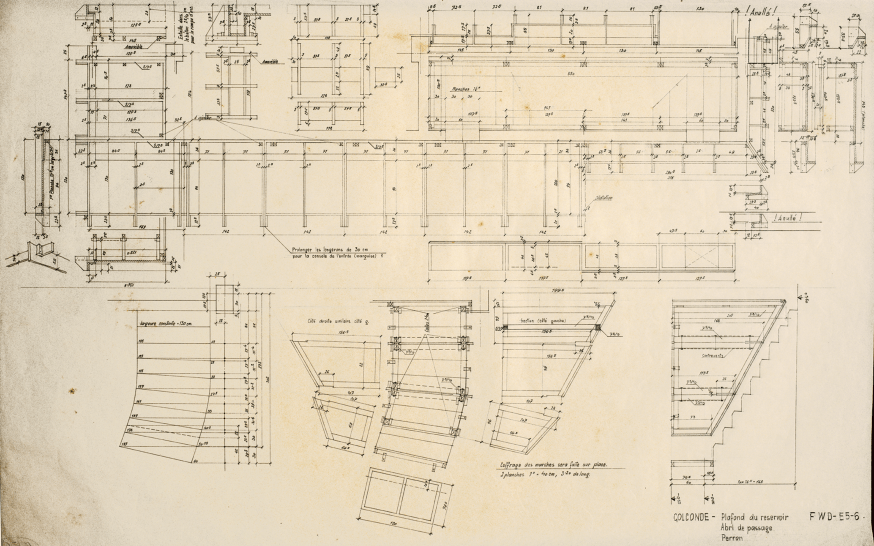

And so beautifully drawn, these original pen and ink drawings were done by Nakashima to design the formwork to pour the concrete with teak shuttering (referring to image 24). And there is a whole set of these shuttering drawings, that are in the archives in Golconde, and they developed in addition to the sections, these are called the formwork drawings (referring to image 25), all drawn by Nakashima, Udar Pinto, two or three other devotees that he was training there to teach the labour how to erect the formwork, which would allow this concrete to be poured.

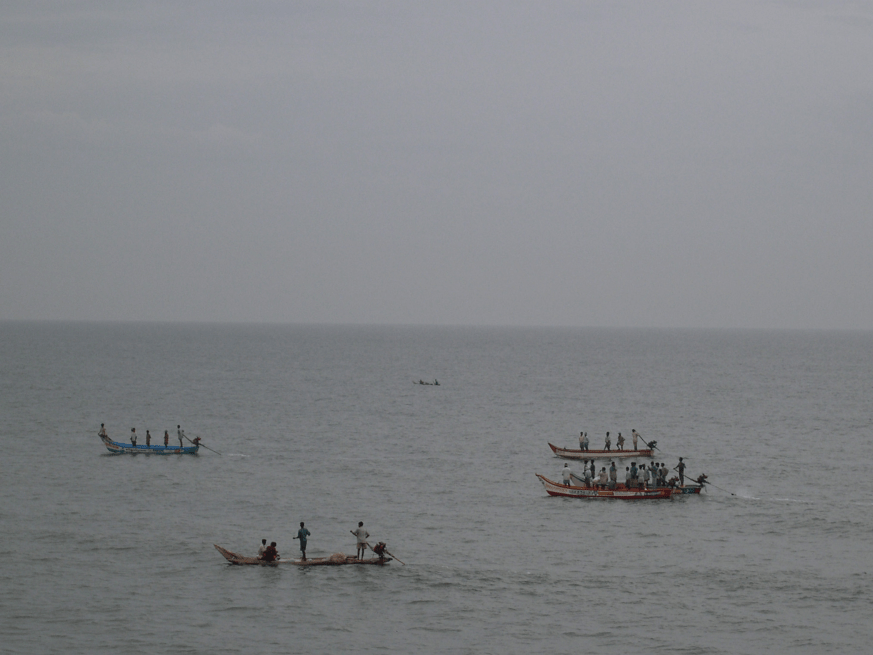

Every single bar of steel was labelled (referring to image 26). Now the steel, like I said, was being imported and Pondicherry did not have a harbour. So, the boats had to dock about a kilometre off-shore and the Mother organized some fishermen to take fishing boats out to the ship, to load the steel from the steamer onto the fishing boats and bring them back to the beach. Nakashima writes in his journal that by the time the steel landed on the beach, it was like spaghetti. It was like noodles- it all twisted and bent out of shape. And so, the Mother sent a hundred fishermen with hammers and they laid the steel out on the sand and they hand hammered the rod straight. And she said, not an inch of steel is to be wasted and so all of these reinforcement drawings (referring to image 27) were designed and detailed in Pondicherry by Nakashima. And really, I mean, our structural engineer, Himanshu Parekh for many years has taught us the value of not having wastage in the way we design our laps. But that really started here in 1939.

And this is what they must have done (referring to image 28). This is a scene that we would witness every morning as we woke up in Pondicherry at Golconde. But literally, the boats were like this. They would go out, unload the steel from the steamer, bring them back to the beach, and hammer them straight.

These are photographs we found, construction photographs of Golconde from 1958, taken by an early photographer of the Ashram, Robi Ganguly (referring to image 29). So, Robi-da was given a camera by the Mother, and she said, “because this is the first time a building like this is being built in India, you must document every stage”. So again, a really expansive sense of the importance of this endeavor. Sri Aurobindo himself wrote in a letter to Raymond that this building had to distil principles of morality and ethics into the expression of the architecture. Every piece of work that was being done was in a sense embodying the value system of the Ashram, which was the attainment of spiritual and mental peace through the labour of highly refined and practiced integrity.

Before the word sustainability was coined in our profession, they decided that leaving the concrete exposed to the Pondicherry sun would be unbearable in the summer (referring to image 30). So between 1940-1941, precast concrete walls were designed to create this airspace to allow the passage of the breeze through the roof, between the roof slab and the ceiling and the roof tiles, keeping the building extraordinarily cool. We spent our time in Golconde, which coincided with the months of May, June, and July, which are the hottest months of the year in Pondicherry and stayed in the building with no electricity, no fan, no air conditioning, the rooms were incredibly pleasant to inhabit still.

You can see the detail of the breeze going through the slab and at the edge of the roof you see these iron clips (referring to image 31). These could be rotated because they were worried that in the cyclones if any of the tiles broke, they would have to be replaced. In the 70-odd years, since the building has been in existence, not a single tile has been replaced yet. Again, as architects practising in this country, I think the recurring lesson of this kind of work is the outstanding synergy between the design intent, the client’s appreciation of that intent and the construction, and the integrity of the materials deployed to make it. I was surprised because in all my years of travelling and working in India, I had never seen a building of this age in the condition of this meticulous preservation.

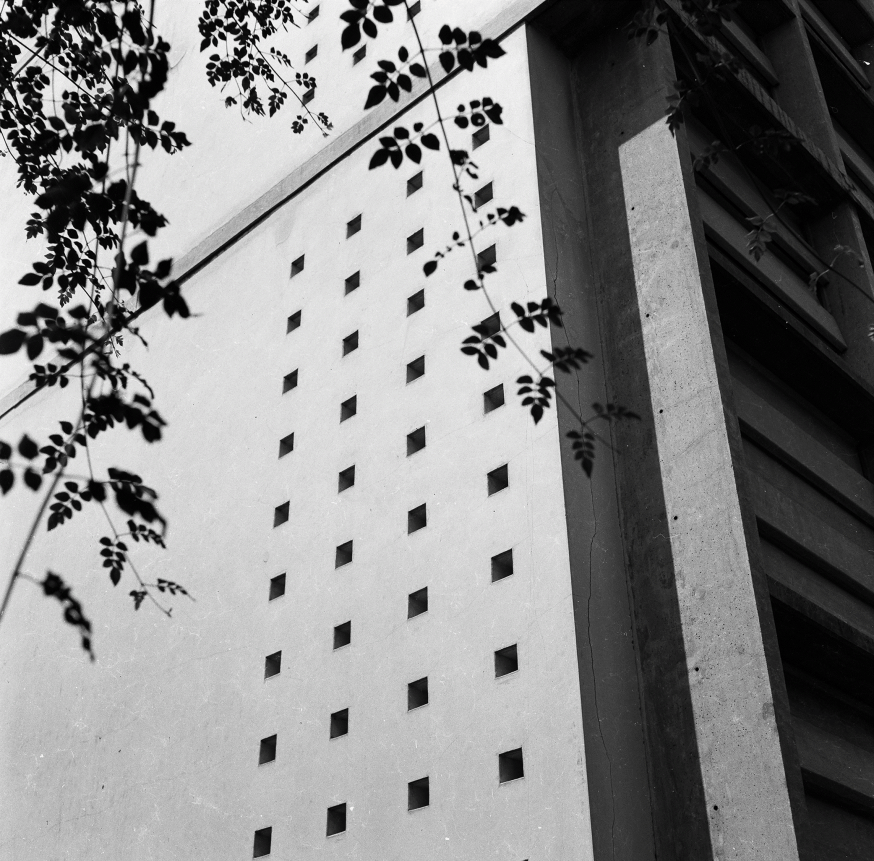

This is an early Robi-da photograph (referring to image 33). The Mother was very clear that the building and the austerity in its architecture had to be counteracted by the presence of a garden. She called it the sheath of tranquillity and the sheath of tranquillity was the idea that even the boundary wall was open almost like a monastic cloister for these devotees; a very private place, but this sheath was this foliage that would be created outside.

There was no hardware industry in India at that point. There was no such thing as building hardware and now, Nakashima and Raymond have designed these operable cement-asbestos louvers to be modulating the breeze and the light and so they had to design the hardware (referring to image 34), but given that the war was on and there was no steel foundry or casting industry there at that point, the Mother organized the collection of all the brass vessels from the Ashram and they created a foundry on site. It is still there today in Pondicherry. All of these utensils were collected from the devotees and the Ashram, melted down. Hardware was designed and built by Nakashima on-site and then used to operate these louvers and I will show you photographs because even today that hardware functions perfectly.

So again, you see the presence of the building in the garden. This is the south facade (referring to image 35), a very large Gulmohar tree shades the southern garden. There is a water channel that runs through the garden, collecting all of the rainwater, and harnessing it in an underground tank and that water is used for cleaning and gardening, again very progressive. There, you see the hardware (referring to image 36). The brass hardware that was cast by the melting of the utensils to lower and raise these louvers, a thousand louvers were cast as extras. Again, having never done this before, they were concerned that, with the wind speeds and storms and cyclones, these louvers might shatter and break. Again, all thousand louvers are still on the site in a basement room. They have never been used, because not a single louver has broken.

There is a detail of that hardware (referring to image 37). It is amazing to think this was the first pouring of concrete in India. Look at that, look at the reveals, look at the edges (referring to image 38). That is how the building sits on the site (referring to image 39). It is almost kind of forbidding austere, anonymous little slit in the concrete wall.

You arrive into this foyer space where you are given your first glimpse of the garden and the water channels that are being used to collect all the rainwater and then this black kadappa stone floor with a kind of slightly curved stair that leads you to the upper lobby (referring to image 40), and really this is in no sense of the word, a public building – it is an entirely private building. We were very lucky to be allowed to stay there and to spend a few nights there. But as we were always reminded, this was a kind of spiritual haven for these 35-odd people who had made this their home. And so in that sense, it was meant to isolate them from the world and secure them from the tribulations of the world outside.

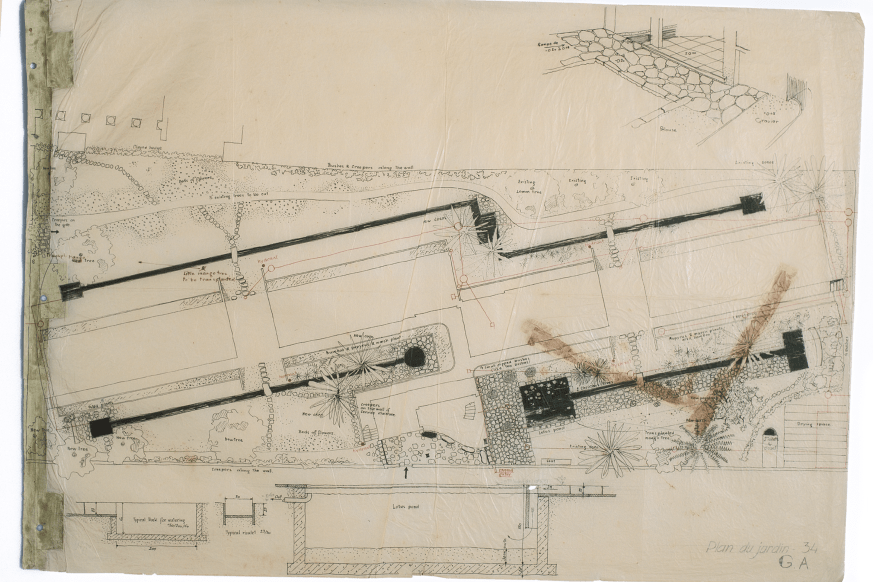

[21:35] I think, as the late Professor Shahir said to me one day, as he was in our office and I showed him this drawing (referring to image 41), that it might just be the first modern landscape site plan in India.

And here it is, it is showing the footprint of the building, it is showing the rainwater channels, it is showing the planting strategy, again, a very tight site. So by rotating the building to that axis, the triangle shape gardens that resulted on the north and south were very carefully, sculpturally planted to create this haven of landscape and tranquillity. You can see even the sketch done by Nakashima showing the pattern of the flagstones to be laid at the entrance. There it is (referring to image 42).

Probably in homage to his Japanese ancestry, a very small Japanese stone shrine was carved and placed at the front, in between the reflecting pool and the boundary wall (referring to image 42). This is the passage between the two breezeways just coming up the stairs and you can see beyond, straight through, is the Bay of Bengal (referring to image 43). Detail of that garden now (referring to image 44). This was a photograph that Christine, I think, took in 2003 when we were living there. The Gulmohar tree, which is now massive, essentially takes up the entire south garden (referring to image 45) and the south garden again (referring to image 49).

Now that lower floor where you see the small circular apertures in the concrete (referring to image 47), that was all the services. So, there was a pantry, there was a laundry room, there was a staff room for the staff that comes every morning to wash and clean the building, and literally the building is washed and cleaned. All the walls are scrubbed, and the floors are scrubbed. The walls have no paint, the walls were pigmented; layered with a pigment made with albumin, eggshells crushed with lentils and seashells, and it was a primitive version of lime plaster. They were all plastered and they have never been re-plastered since. So, they are washed once a week with wet rags, but the floor is cleaned every single day. Once a year with razor blades, all the kadappa stone is scrapped by hand.

So, you get a sense of the atmospherics of the site (referring to image 46 & 48), and the atmospherics of the building. And I think in our research and reading the original letters and Nakashima’s journals, it was very clear that this was not a building designed in isolation by a single autonomous genius architect. This was very much a listening, a very careful and sensitive listening and conversation dialogue between the Mother, and George Nakashima and Antonin Raymond. There were many other local engineers who were also devotees. Chandulal was an electrical engineer who was a devotee, as I mentioned Udar Pinto was an aeronautical engineer who had trained in England, and come back with his wife, Mona to live in the Ashram.

And so, Nakashima had a roving band of fellow engineers. In the diaries that we found, things were not always pleasant – there were very heated arguments, there was a lot of ego involved, a lot of testiness and the Mother really acted as a referee or an umpire. Nakashima at one point wrote saying he could no longer work on this building because one of the engineers made his task impossible and she wrote back saying, “well, I think you guys will need to harmonize your differences”. So again, very interesting, glimpse into what it took to maintain, preserve, create this quality and standard of excellence by the client.

That is a view of the breezeways that are in the lower ground floor (referring to image 51) and so every evening at three o’clock, the devotees gather. You can see the cast-in-place concrete benches, cantilevered from the walls, the teak furniture made by Nakashima, and they gather here for tea in the afternoon (referring to image 52). So really even the nuances and the syncopation of your daily life were calibrated into some of the architectural spaces that were earmarked for this.

That is the laundry room on the other side of the plan (referring to image 53). You can see the cast-in-place concrete sink, the buckets, the benches, and all the floors were draining so that even the laundry water was collected and taken to the garden.

It became very clear to us as we researched this building that the patterns of use were completely understood and factored into the design. So you can see that every morning, the two-hour process of washing, folding the laundry, and then taking it up to the residence is all done on this plinth (referring to image 55) and this plinth is a concrete water tank that collects the rainwater from the terrace and you can see the height has been calibrated so that actually acts like a piece of furniture. And there was a wonderful sight every morning, between 9:30 and noon, where a line of 14 or 15 workers would in their coloured saris would be adding this vital presence to the building and there were layers and layers of this laundry being folded on this building, on this plinth. If you can see (referring to images 53 and 54), here are the pivoting windows. Again, the hardware was designed to allow the breeze to ventilate the subterranean rooms and here all the louvers are now closed. So, every morning those louvers were opened and closed depending on the circumstances of the temperature.

And then, in a remarkable page of specifications, Nakashima writes that the teak logs, that would be the banister of the building (referring to image 57), would be installed in all their glorious imperfection- not a knot was to be filled, not a gouge was to be filled or sanded, but that the teak would reflect its own ontological integrity, contrasting the polished oil teak with a kadappa stone and the poured concrete. So, you can see the kind of sensuality or the kind of tactility that the building sought to achieve was also manifest with the integrity of each of those materials, starting with the flagstones that were drawn in that landscape plan, the kadappa stone in the upper terrace, the kadappa lining the stairs, the poured concrete and the teak. So really, an extraordinary attention to detail and these long slabs of the banisters are just anchored top and bottom to the landings with the brass bolts that were again, cast on the site.

And, this is a typical corridor (referring to image 58). So, it is a single loaded corridor, the sliding teak doors are the doors to the rooms, and then the asbestos concrete louvers are the apertures to the garden. And even the design of the doors, the teak was woven. Since there was no electricity, there were no fans, the teak was woven so that the privacy would not be compromised but that with the louvers open, the breeze could come through the garden into the rooms, through the slatted openings of the teak louvers and the top was left translucent with fluted glass and the edges of the corridors have these circular openings cast into the concrete. So, it is a naturally breathing, passively ventilated building.

This is an archival photo of Robi Ganguly (referring to image 59). The first photo essay that we found on Golconde, actually the photographs were taken by Henri Cartier-Bresson. He had come to India in the 1940s. Of course, you are familiar with the photographs he took of Gandhi and Gandhiji’s funeral, but he actually came and spent two weeks in Golconde and so there is an entire folio of the original architectural photographs taken by Cartier-Bresson of this building. Again, telling you that even at that time, although this building disappeared from the canon of Indian history, the most noteworthy protagonists of the time in the cultural world, were aware of its making. They were aware of its existence.

Again, all the furniture designed by Nakashima, the desk, the chair with cane (referring to image 60), there is a photograph of the Mother and Sri Aurobindo on every desk, the armoire and these are full-scale drawings (referring to image 61). These were all done by Nakashima, and as his daughter Mira told Christine and I, when we went to visit her in New Hope several years later, that this was the beginning of Nakashima’s career as a woodworker. Today in the United States and the world over he is most well-known not for his architecture, which is actually quite extraordinary because he was an amazing architect, but because of his furniture. And these were the first drawings that he developed onsite to design all of the furniture that would be placed in the rooms (referring to image 61).

[30:18] This is the chair with the straw cane (referring to image 61). This is the lamp that he designed and developed (referring to image 62).

The glass was cast in Pondicherry. Udar Pinto being an engineer had worked on the design of aircraft and ships. So he designed all the toiletries and the toilet fixtures, including, you can see the tube below the sink, the bottle trap (referring to image 63), and the taps, the handrails for the service stairs (referring to image 64), the laundry terrace, the hooks to hang the laundry, and we see those drains on the laundry trays that the slab is slightly bowed in two directions so that the drips from the sheets that are drying every morning are collected in that drain; on drains on both sides and taken to the garden (referring to image 65).

So, an extreme sense of frugality. I know my friend Riyaz talks about the architecture of Gandhi, and I think there is a very strong similarity between the austerity and the frugality, of both practices.

And that is Mona Pinto with her troop, as she called them “my Golconde ladies” (referring to image 68). This was the core team that was responsible for the upkeep and the maintenance of the building every day. That is the morning, the cleaning is going on (referring to image 69), the water jugs, the sarais are being filled (referring to image 70). The pantry, subterranean, keeping everything cool (referring to image 71).

In one passage, Nakashima writes about the ants, the beastly ants that would infect all the food and take over everything. He said “We have even tried designing the cupboards” (referring to image 72). These are every resident’s personal pantry – these boxes designed by Nakashima. He said, “We even floated little cups of water below the legs, and these ants learned how to swim. So, they would lie on their backs, float across the water, then climb the legs of the furniture and get all the food.” So finally, they discovered that they put a mixture of soda ash, in the bottom of the cups to keep the pantry safe from the ants.

The drains that were cast, for all the rainwater (referring to image 73). The concrete allowing for the soil and waste pipes to be flushed with the surface (referring to image 74). Detail of the laundry stair handrails (referring to image 76). Notice they even embedded a texture on the concrete (referring to image 77) so that people carrying wet laundry, bare feet, in their saris would not slip. Pretty remarkable, given it is the first time the material was being deployed in the country.

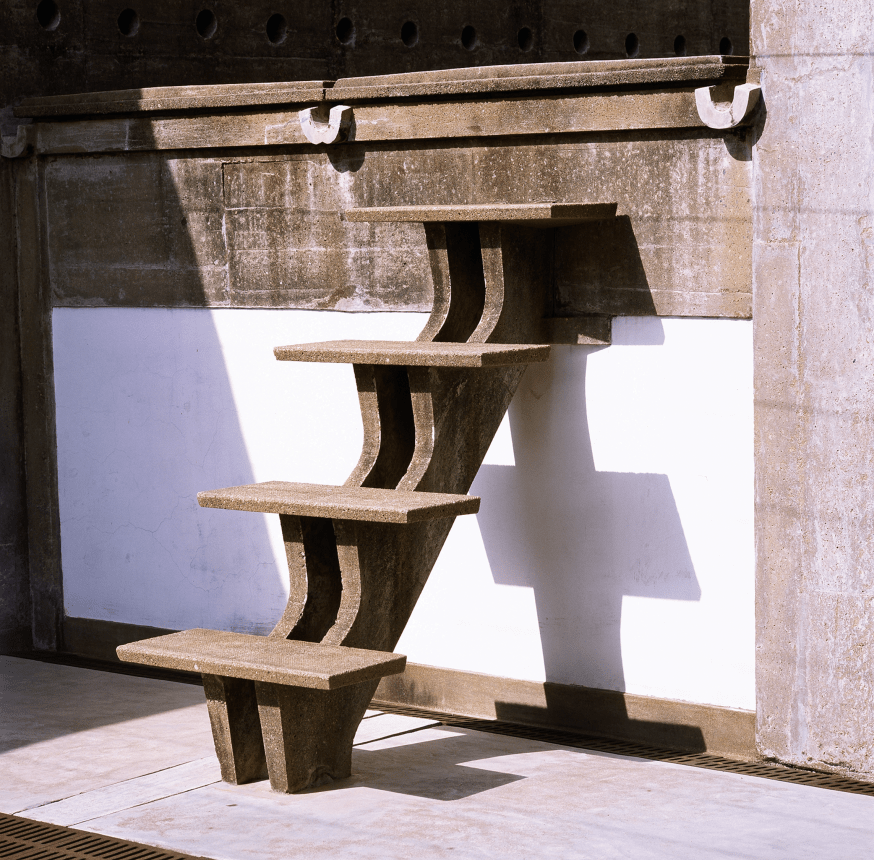

The louvers through which you glimpse the garden (referring to image 78), all the hardware, the bolts, the handles, all cast on-site and brass against the polish of the teak (referring to image 79). The teak is oiled every three years. It has been a non-stop continuous practice at the Ashram every three years. All of the teak is oiled. The lamps that were made for each room (referring to image 80). The hinges and the hardware for the teak doors are directly embedded into the RCC (referring to image 81), into the concrete frame. And I think probably the most beautiful first piece of concrete cast in this country, the laundry stair, I mean, such a profound act of sculptural elegance (referring to image 82). And this one was pre-cast. It was pre-cast in the gardens of Golconde and then carried upstairs and assembled for the upper terrace of the laundry.

The entrance canopy was covered in China mosaic tile, to collect all the rainwater into the systems (referring to image 83) and then the anonymity of the boundary wall with now very profuse garden, and the Lotus flower, which was the Mother’s favourite flower, embossed on the door in brass (referring to image 84).

The morning greeting in front of Golconde to tell you, you have arrived, you are welcome (referring to image 85). And that is the building (referring to image 86) and that is the garden (referring to image 87).

Pankaj Vir Gupta is a licensed architect in the United States, and a registered member of the Council of Indian Architects. As founding partner of vir.mueller architects, he has led the office on award-winning projects, across a range of typologies and scales. The work of vir.mueller architects has been published and awarded internationally, and the firm continues to advance design thinking in significant built works of architecture. Recent projects include the University of Chicago Center in India, and the Humayun’s Tomb Site Museum – the first contemporary museum in India to be built on a World Heritage Site.

Since 2012, Pankaj has taught as a Professor of Architecture at the University of Virginia School of Architecture, where he co-founded The Yamuna River Project – the largest multi-disciplinary, pan-university research initiative. As Co-Director of the Yamuna River Project, he teaches an Advanced Design Studio each year focused on the predicaments of Mega Cities. He has previously taught at the University of Texas at Austin, the Arizona State University, and the University of New Mexico – where he received the Dean’s Award for Excellence in Teaching, as well as the J.B. Jackson grant award for research.

Pankaj Vir Gupta received a Bachelor of Science in Architecture from the University of Virginia (1993), and a Master of Architecture from the Graduate School of Architecture at Yale University (1997).

FRAME is an independent, biennial professional conclave on contemporary architecture in India curated by Matter and organised in partnership with H & R Johnson (India) and Takshila Educational Society. The intent of the conclave is to provoke thought on issues that are pertinent to pedagogy and practice of architecture in India. The first edition was organised on 16th, 17th and 18th August 2019.

Organisation and Curation: MATTER

Supported by: H & R Johnson (India) and Takshila Educational Society