An editorial project by Matter in partnership with Şişecam Flat Glass, PRAXIS investigates the work and positions of diverse contemporary architecture practices in India. This episode features a discussion with Sunitha Kondur and Bijoy Ramachandran from the Bengaluru-based practice, Hundredhands. Their work spans public and private typologies with an intent to navigate abstract as well as real world conditions. Reflecting on their journey from the years of study at MIT, collaborations within and outside India, family, peer groups in Bengaluru, the conversation delves into the grounding influences and ideologies that have shaped over twenty years of practice. At the core of the practice is, as they articulate, ‘how does one create places of intimacy, places for congregation, places for celebration’.

EXCERPTS FROM THE INTERVIEW:

BR: Bijoy Ramachandran

SK: Sunitha Kondur

FOUNDATION

<00:35>

BR: I do not have any architects in the family; I had a wonderful teacher in boarding school who suggested that I should pursue architecture. So, I applied in multiple places and managed to get in at BMS College of Engineering. Knowing nothing about the practice, the profession, and having no internet [..] you are getting in completely cold. But BMS was a completely open environment. ‘Open’ is a very generous term to use. It was devoid of real instructions. There were few teachers who were really good, but by and large it ran on auto-pilot.

What that meant was that a lot of us had to figure out our own ways for work; to find or to seek out people who have seen better things or who have read things, or who are doing work that excited us. We gravitated towards our seniors. That was the culture at BMS. The juniors helped the seniors with their projects and in the process of doing that, they learnt and improved.

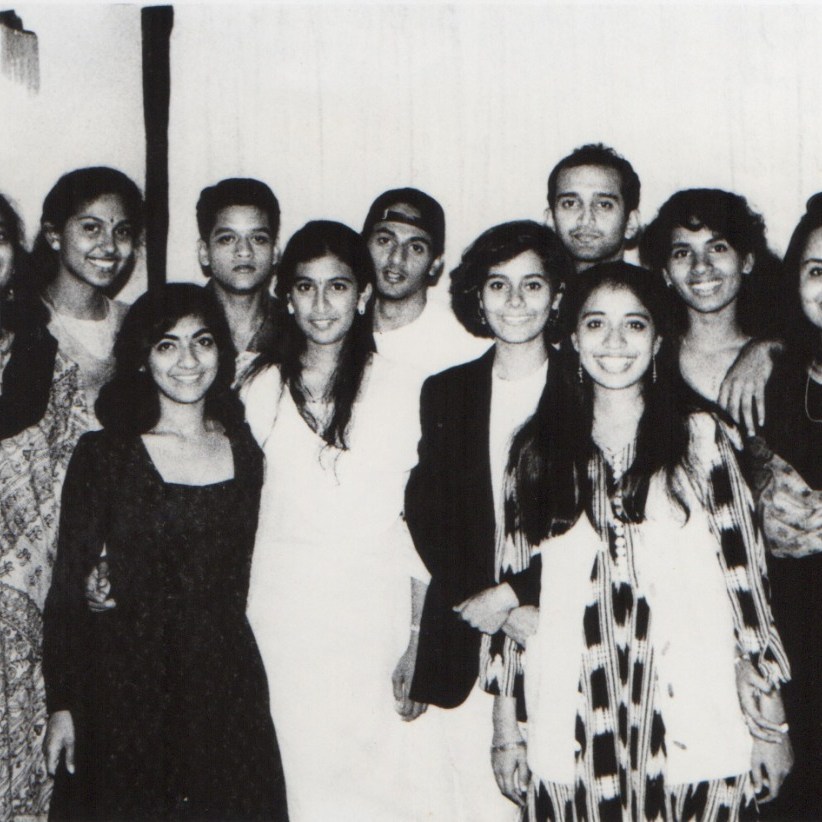

Of course, a big part of BMS was NASA. We were on a yearly scheme, there were no semesters those days. So, we would spend the first six months of the year working on NASA, and then in the final four months we would work on the college submission. NASA was really the focus of at least three years out of my five years of architecture. And of course, we won trophies, but it was also thanks to NASA that I met Sunitha.

<02:21>

SK: My first interaction with architecture was helping a neighbour of mine do her thesis work when I was in my twelfth grade. I always wanted to be a doctor and suddenly there was this option that did not have math in it, so I decided to apply. Then I made it to architecture and not to medical school and started my architecture course. Like Bijoy said, it was all learning from seniors during NASA and a few good professors that we had, but largely, it was a lot of self-learning and finding resources. We used to be at CEPT all the time to use the library and bring back photocopied books at the end of the trip and that was how most of our education was.

<06.37>

BR: Massachusetts Institute of Technology was a very open environment; you have very few required credits […] Structuring your course with your advisor is a big part of the two years. In fact, it is the education. How do you structure two years of your life to pick the things that then are in some sense related but are also projecting to a new sort of situation? That was initially quite overwhelming but then you started to get a sense of this rather large set of things on offer.

I specifically speak often about Julian Beinart who taught the course on cities called Theory of City Form which was started by Kevin Lynch, but what these courses and a lot of these professors did in those courses was to make what you were studying seen in the context of the larger network of things.

If you are thinking of architecture or city or city form or urban design then you were not thinking of them as isolated and they were connected to economics and politics and sociology and that was something really new for me. Of course, you get a sense of it when you are living in the world, but when you are studying architecture somehow you are siloed. You think that this is all there is to the world and then this education really opened up my mind and my eyes to this condition that everything is related in a way […]

Of course, MIT attracts really wonderful students in the master’s program, so that was also a huge learning for us. We had great colleagues from South Africa, Cuba, Turkey, America. We learned from each other what it takes to make the world go around. It gives us a sense of how people’s opinions are formed, what prejudices we carry, etc. […]

In a way it is a bit like what Rushdie says about being in India. You are really close to the screen; it is all dancing pixels and you cannot make anything out and as you move further and further away, you are now in the balcony, so you can see the whole image coming into clarity. That distance, whether it is for education or even travel, brings you out into a place that is unfamiliar, and in that unfamiliarity, you realise certain particular things about yourself.

<10:48>

BR: Fred was one of the people whom we read as part of our Urban Design program. Fred Koetter wrote the book with Colin Rowe called Collage City. It was unbelievable that I was then soon after in Fred’s office. I have worked in two offices in the US, in Fred’s office and in Cooper Robertson & Partners, another office in New York. But the time at Fred’s office was really instrumental in shaping the way that we practice here now. A very iterative practice, based on experience, based on models, so that you get a sense of what it feels like to be in the spaces that you are designing. This in-depth design process at Fred’s office, drove us to investigate as closely as possible to make sure that we were doing the right thing. […]

There is a great essay in the Koetter Kim book in which Colin Rowe makes this distinction between Fred and Susie, and their great talents and he says that Susie makes the framework only in which, Fred’s incandescent intelligence can flourish. Because if Susie’s framework is not there, there is no way for Fred to operate in the world. It reminds me of Sunitha, in a way.

<12.45>

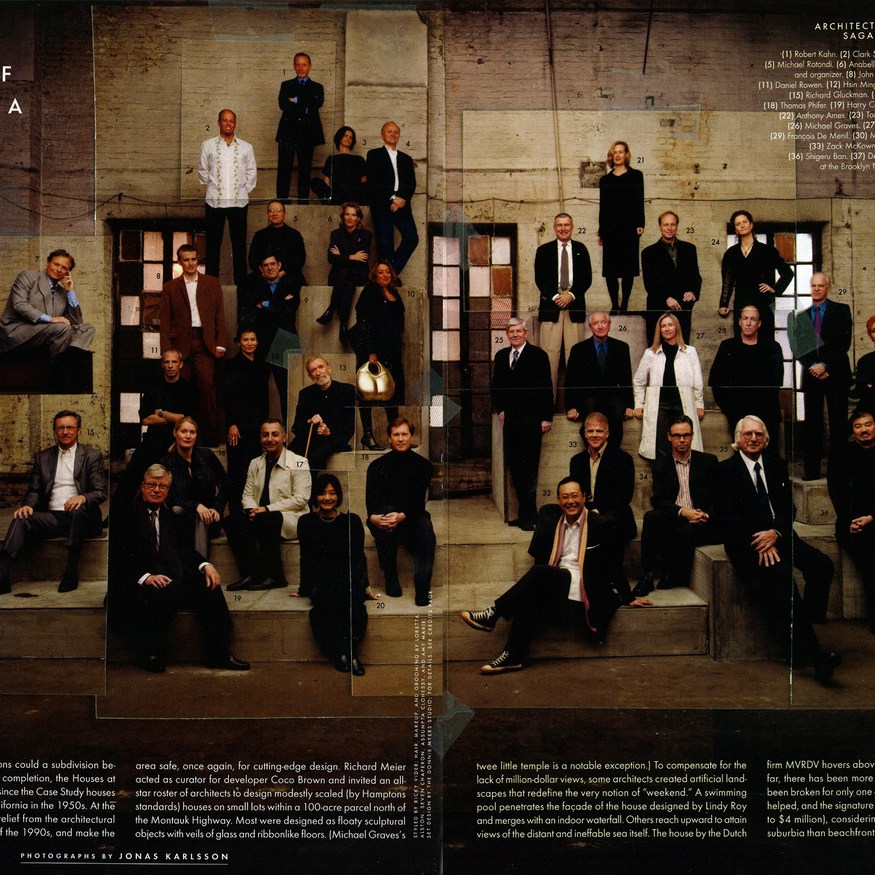

SK: I graduated from MIT and started working with Massachusetts State College Building Authority as a Junior Project Manager, which was a wonderful little office which was managing all the state colleges in the state of Massachusetts. But suddenly there was an interesting opportunity that came by and with a project in New York which was being done by The Brown Companies and Coco Brown. He was a big real estate maverick out of Manhattan who wanted to put together a bunch of architects both young and very established and have them each design a house for his company which was questioning the mansions of the Hamptons, and to do a very well-designed house with a modest budget. He went along and invited Richard Meier to draw up a list of architects. They had a list of thirty-two young and old architects like Philip Johnson and Zaha Hadid and Richard Rogers on the list and so they needed a project manager for it.

[…] I ended up applying and got a call from Coco and he said, “I found your resume very interesting, I know of no architects who also study real estate.” He invited me for an interview and I did not hear from them for a good six months and I had already started working at the Massachusetts College Building Authority, and suddenly I got a call that they were ready and asked me to join them. Then we had to decide, and we moved to New York and the project was something of a fantasy. It was a very small office and we did everything from design management to sales and marketing and publishing a book on the project. It was such a wonderful experience to be able to sit across the table with Philip Johnson, critting his plans for a little tiny house in the Hamptons. We continued working for another year and decided it was time to move back to India, because we saw a lot of opportunity here to start our own practice which was always the plan. We came back and set up Hundredhands.

<21:08>

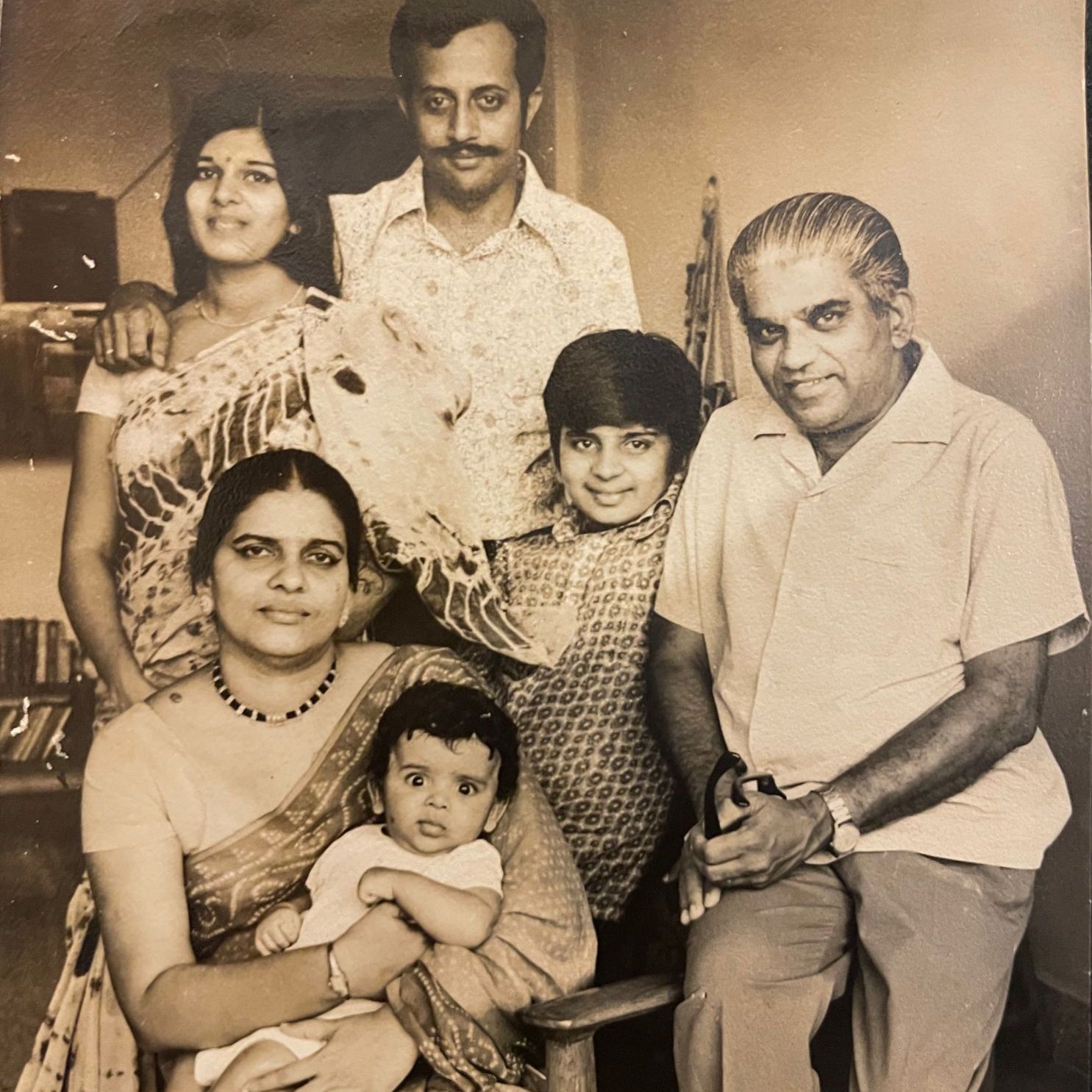

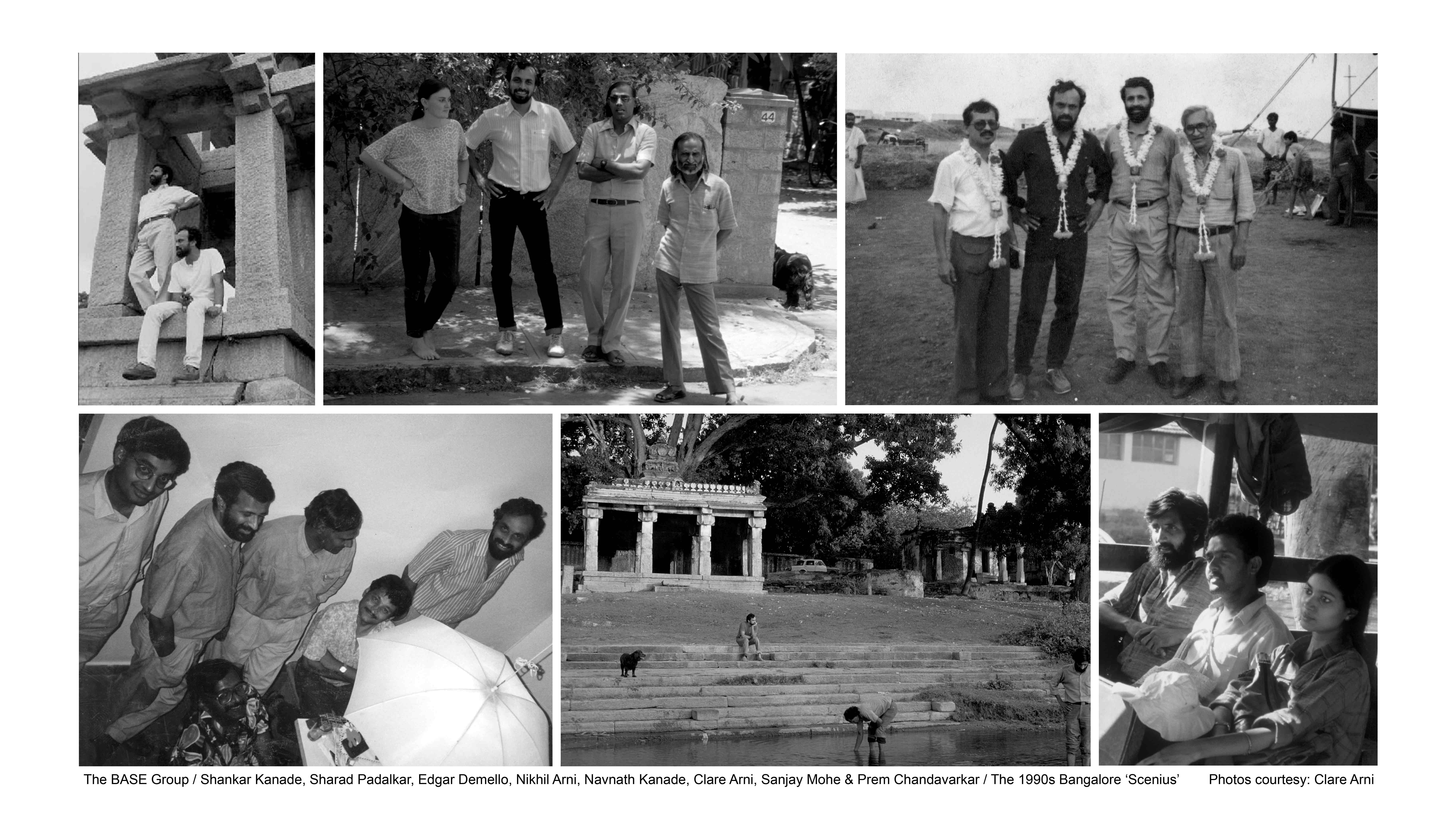

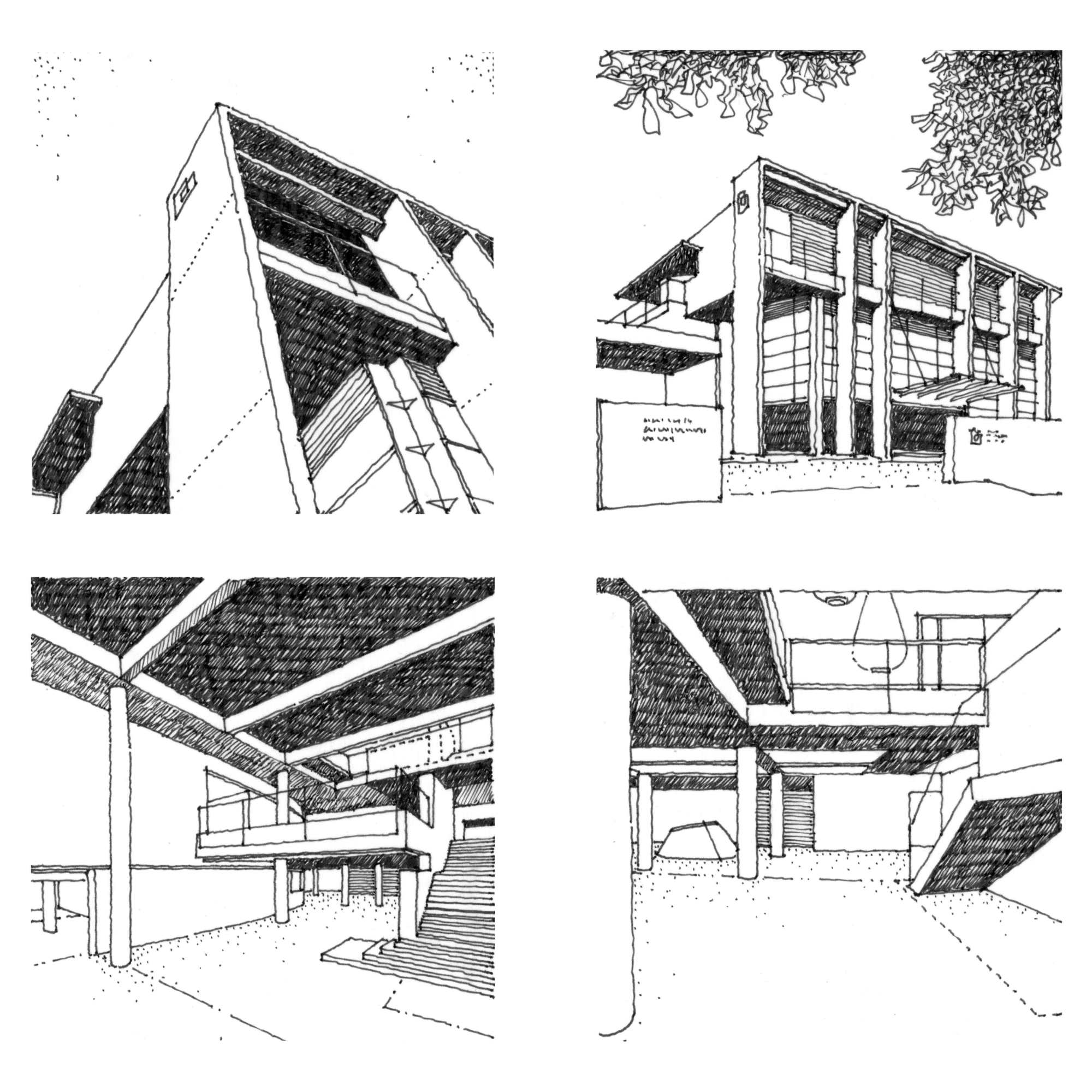

BR: This time in Bengaluru during the sixties and seventies was when the Raman Research Institute is building their new building that Venkataramanan did which was the first exposed concrete building in Bengaluru with shuttering coming from Jammu. For the first time ever the IISC was setting up huge new buildings, so there was a whole bunch of action there. Charles Correa’s building is on that campus, he was doing the Centre for Scientific Research and Doshi was doing IIM in the late seventies. So, at that time something was happening in the city, there was suddenly dramatic modern architecture coming into the city and that was bringing people like Correa, people from Kanvinde’s office were here because the housing was being done by his office at IIM. Correa’s people were here, Doshi was here every month; that influences a bunch of people in the city. […]

Nikhil Arni who is Doshi’s favourite student, calls up and says, “God is coming.” Everybody gets ready because Doshi is arriving, Correa is arriving. You have this transfer from that generation, to Nikhil, the Kanades, Padalkar, all of them and that generation passes it on to us. They started having lectures, workshops, talks. […] That culture of some friends coming together impromptu that then creating an adda; that was amazing when we were students that we learnt so much from just being in the company of these people. They would have travelled somewhere and they brought back slides and they showed the slides and argued amongst themselves. That really enriched us.

<23:35>

BR: The second important set of people are the Glenn Murcutt Master Class group […] I was able to attend the master class in 2012, it was a dream that I had for many years, a very expensive proposition to get out there but it was a fantastic two weeks. To be able to go there, spend time in the Boyd Centre which you cannot do anymore because they do not conduct the master class there anymore; to have that one week at the Boyd Centre with Richard, Peter, Glenn, Brit and Lindsay […]

Of course you are talking about architecture, you are doing a project, you are getting crits at the desk etc, but you are also with these guys. You are seeing how they operate in the world, how they engage with others, how they engage with each other how they carry themselves as people, and that I think is the true lesson of the master class with a group of really sophisticated erudite and mature, wise people.

After having done the Master Class we tried to figure out a way to get the Master Class to India because it was so expensive, and we wanted many more people to have this experience of the great teachers. We were fortunate to get the money and support and so we did it twice in India. For our own selfish reasons we wanted to bring Richard here and have time with him on our own and to have it at IIM and to have Doshi at the first edition, we were checking all the boxes with this one.

CULTURE

<25:58>

BR: In very general terms, I usually look at all the architecture and handle architectural projects, Sunitha handles all the interior projects. Sunitha does most of her projects completely independently, in the sense that she runs with them, she has a team that then supports her and she gets them done. My architectural projects are a lot messier than that, because I have to get Sunitha to review everything because I am not really completely sure.

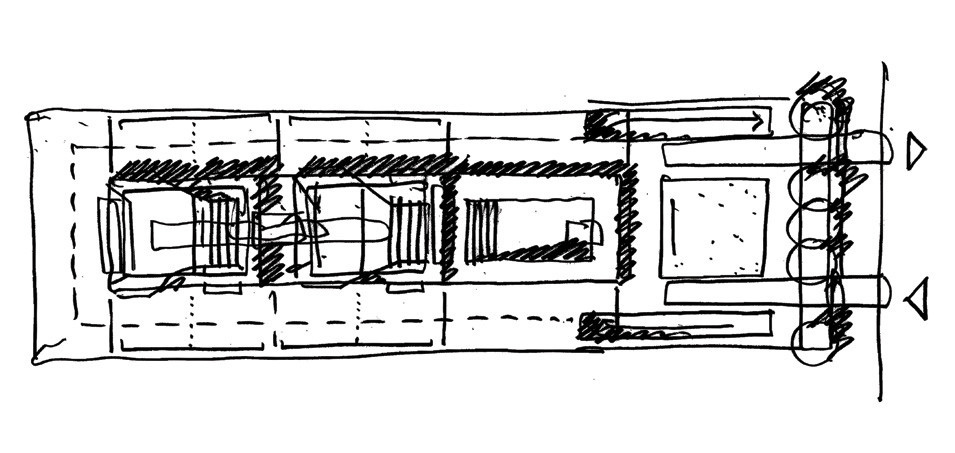

The way that it works usually is that I draw a very rough parti for the program, a general framework on which the program can sit and that then goes out to people in the office to develop plans and sections from. We are often looking at precedent before bringing together certain things that may be pertinent. A lot of our clients have been incredibly forgiving, because we often learn at their expense and many of the better projects that we have done have come as a result of very enlightened clients. People who knew what they wanted, or who pointed us in directions that otherwise we would not have gone.

<29:13>

SK : A learning for young practices is that when you set up a practice you do not come ready with all types of experience. There is no scenario where somebody has already worked on every kind of project there is. It is important that they do not shy away from it. You take it and you give it your best, and there is nothing that you cannot do. We have had such a wide variety of projects that we have started with even in the beginning, we had institutions, hospitality, we had an office building, we had an apartment, all at the same time.

The important learning is that you should not shy away from doing something that you have not dealt with before and to go ahead and take it on.

<30:05>

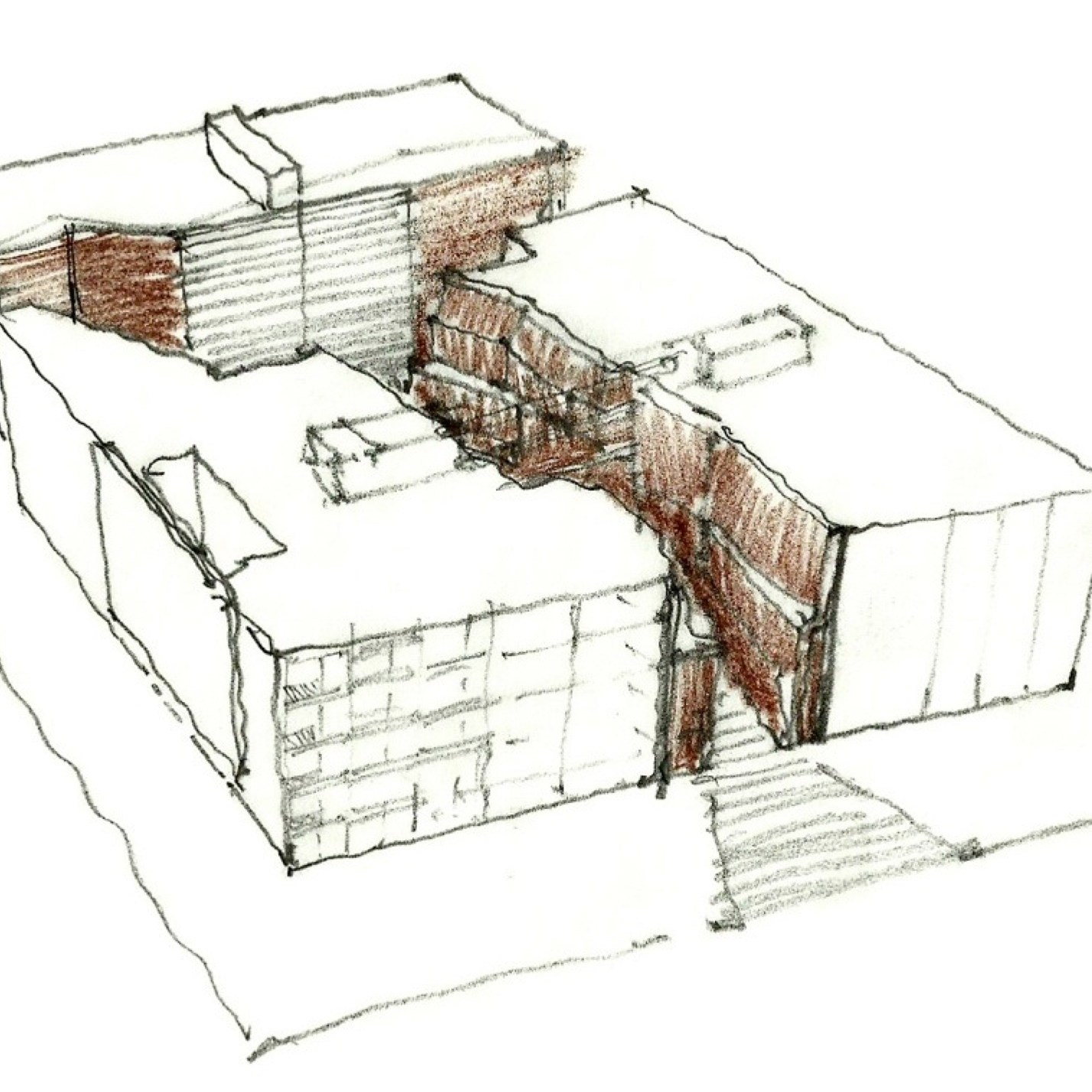

BR: When we were at MIT, Bob Allies bought the Allies and Morrison exhibit to the Stacy gallery at MIT, and I was just blown away. They are one of those really wonderful architects […] They really are just working to do simple buildings extraordinarily well, as Glenn Murcutt says. From that point on, I started writing to Graham. When I came back to India and did the Hope buildings, I would send Graham, without any invitation — pictures of the building, plans of the building. He would write back long letters, with feedback. He would really give us his time and that really was fantastic.

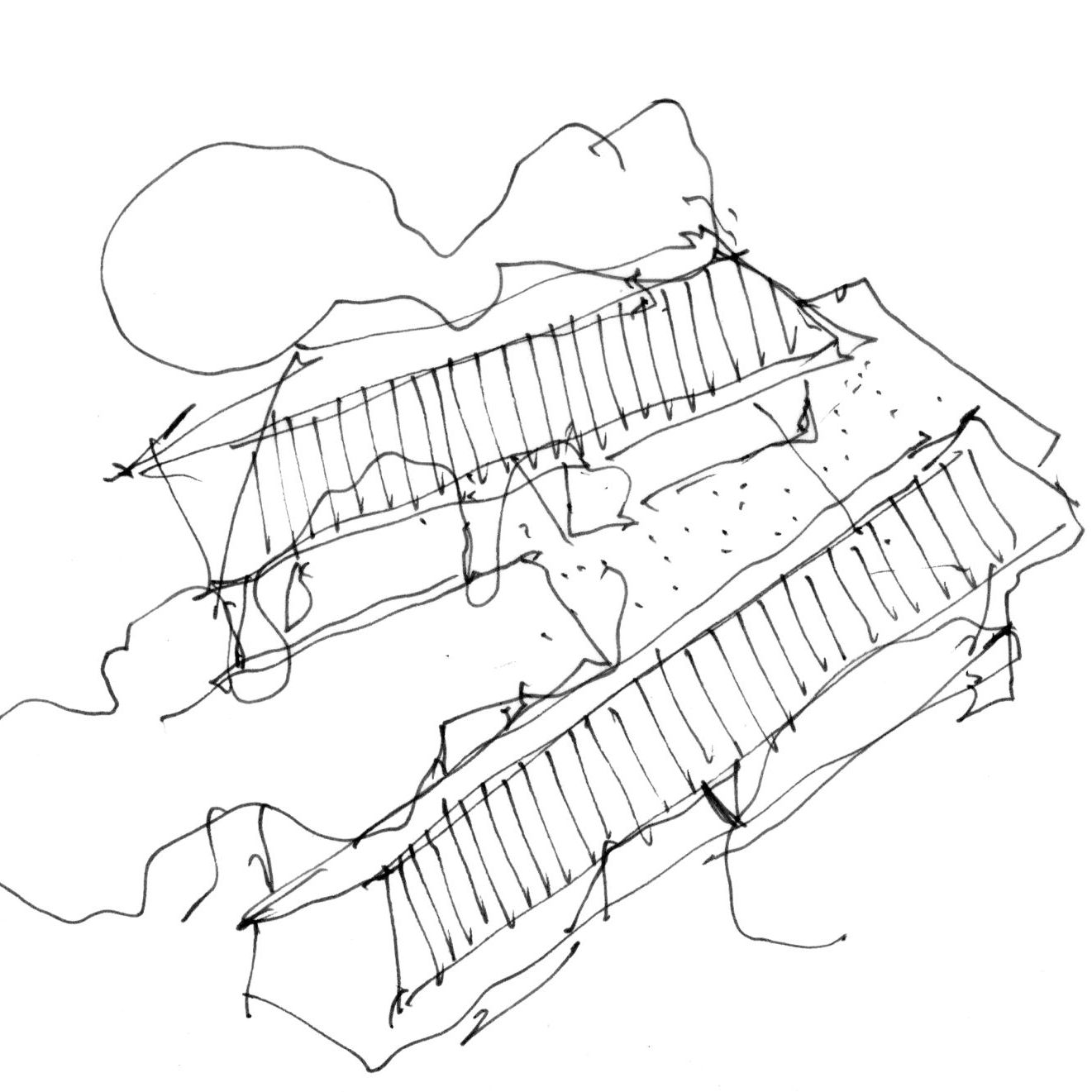

When Gautam wanted to do this large hotel in Whitefield which was on 2 acres, I told him that we would not be able to do this building, it is really complex. There will be some hotel rooms, there is going to be apartments, it is mixed use with services. We do not know anything. […] Just out of the blue, without telling them, I wrote to Graham, […] and I sent him the brief. And he asked if he could speak to his partners there and then maybe make a pitch for it. […] And in three or four weeks we went back, we discussed, and they had come to India.

I remember we did something really smart, I told Gautam that we will put them up in at West End, so they get a sense of this kind of an environment. They stayed in these beautiful rooms with a veranda in front of it and it was completely inside-outside, in this really Bengaluru tropical condition and they got it into their blood. They understood immediately what it was to be in that short trip they made here. That is what a great architect is, he or she figures out the conditions in which one is building and they just got it in a flash.

In three or four weeks they had the whole parti of the building done. Where the hotel rooms are, where the apartments are, what is the cadence of the structure, where is circulation, the fire code; everything in-built into this small model they made for the first presentation. They nailed it.

When you get something of that clarity so early on in the process, the rest of the time you are just developing it to become a fine piece of architecture, because the parti is so strong.

PROCESS

<34:55>

–

<36:29>

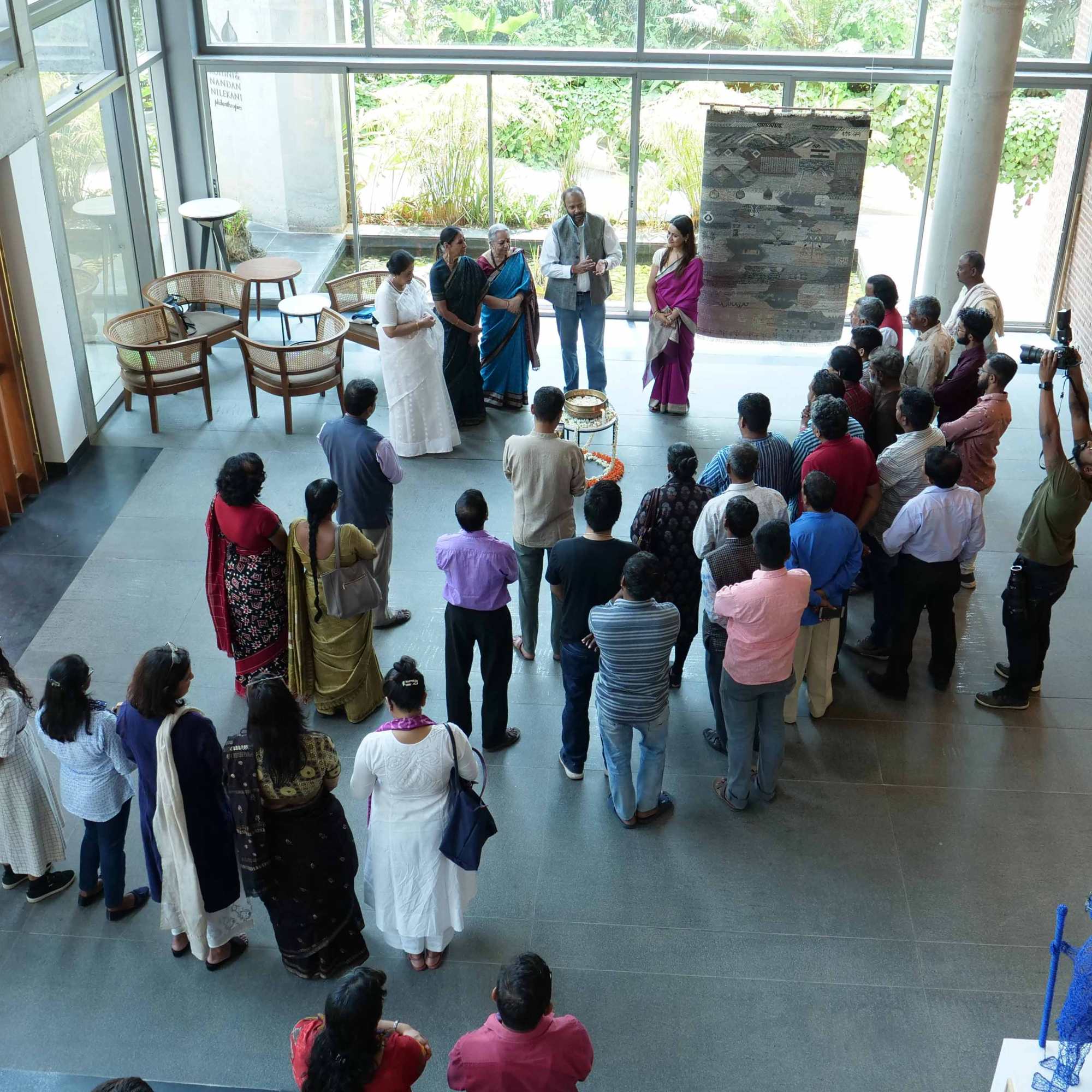

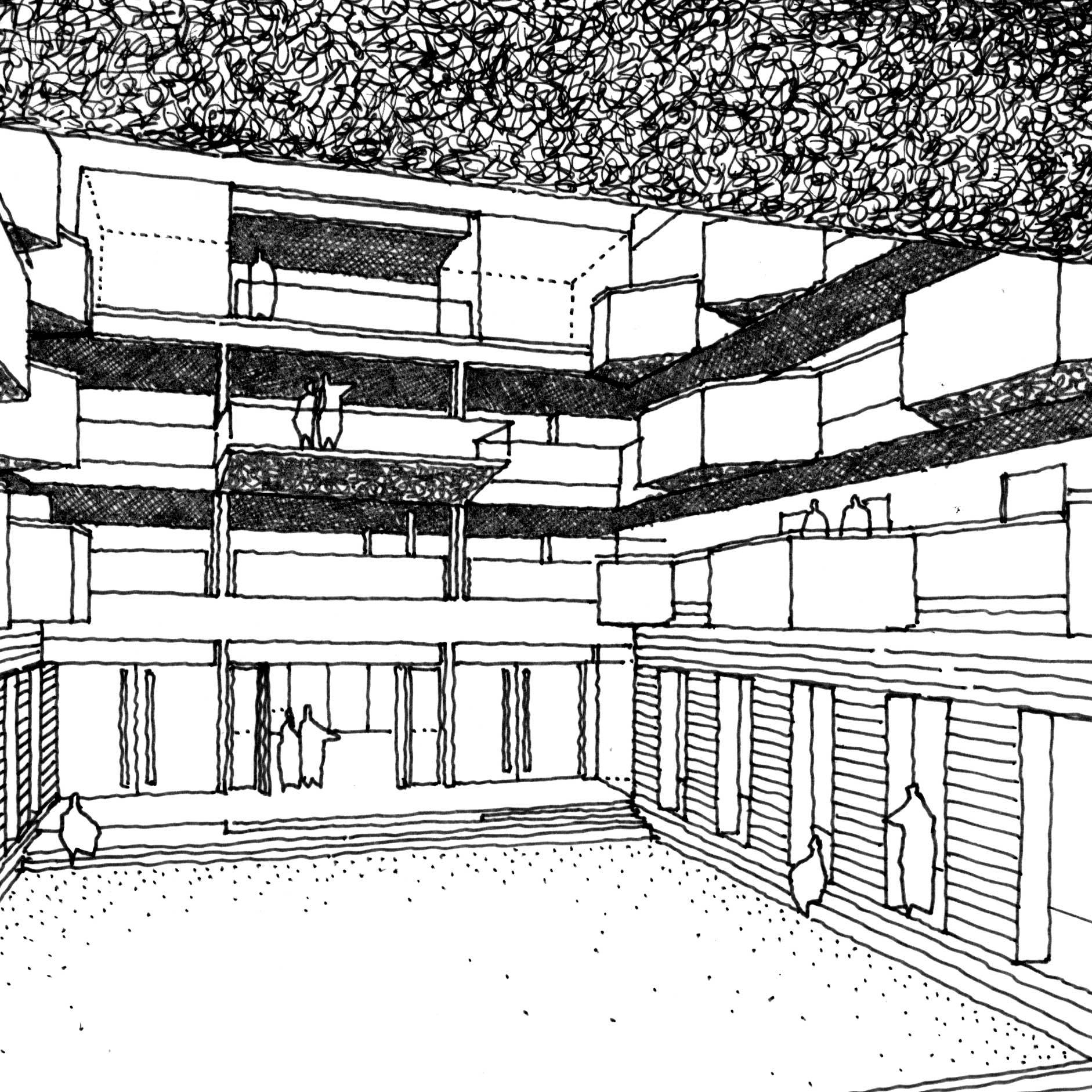

BR: What we are trying to go after at the core of it is like what Richard said, we are just trying to make things that are very comfortable and easy and beautiful places to be in. That drives all of these projects, whether it is the single family home which may be for a very small group of people or the IISC building which is for a very large number of people to use.

At the core of it is just how do you create places of intimacy, places for congregation, places for celebration. If those can be clarified or articulated well in the plan that then becomes a successful project. When you are in the building you feel a certain sense of grace and comfort.

<42:31>

BR: When you draw by hand it intuitively gives you a sense of things. It is like motor memory that if you draw by hand, you understand certain scales and proportions […] The hand remembers those things much more clearly, much better than you do. If you have drawn enough by hand, you can trust the hands to guide you to the right way to lay something out. Fred used to say that if you were to trace out old plans or trace out an old section, you know the cadence of structure intuitively.

<43:25>

BR: A lot of times, we approach work abstractly. We think of architecture in abstract terms and that is valuable. But, for us the great joy of seeing a project completed is when it brings together our understanding of an abstract condition or our ambition to achieve something abstract, but it is also negotiating real world conditions, it is negotiating a client who may be very difficult, it is negotiating a site that may be very challenging, it may be negotiating a program that is really throwing us for a loop.

This confrontation of the idealised Kahn-ian diagram with the messy reality of what the commission is – the coming together of that to create something that is of value is the core value of the practice that we enjoy, and we celebrate. We welcome the involved clients, the nagging clients, we welcome the challenging site, or the budget that does not exist.

<44:58>

The second is the idea of collaboration. We take this notion of collaboration not only in terms of the physical coming together of people but it is also the collaboration that we have in remote ways; that we are drawing from people who may not be in the room, that we are constantly drawing from these relationships that we had with Allies and Morrison, with Glenn Murcutt, with Mohe. We are always bringing to bear in the work these influences and trying to channel the lessons that we learnt from those practices and from those people. That collaboration is a wonderfully generous term that gives our work a place in the larger continuum of all the work.

It is like what Eliot used to say when he talked about the traditional writer – what does it mean to be the traditional artist or to be traditional? He says on one hand one has to know all of literature; you are drawing from history, you are learning about Homer, you are doing Shakespeare you are learning all of what has come before you. But you are also bringing to bear your own current predicament, our own understanding of what the zeitgeist is. What is this condition now that we are confronted with? That is everything to do with circumstance, everything that is coming to the table as part of that conversation and coming together between this knowledge of history and the invitation of circumstance.

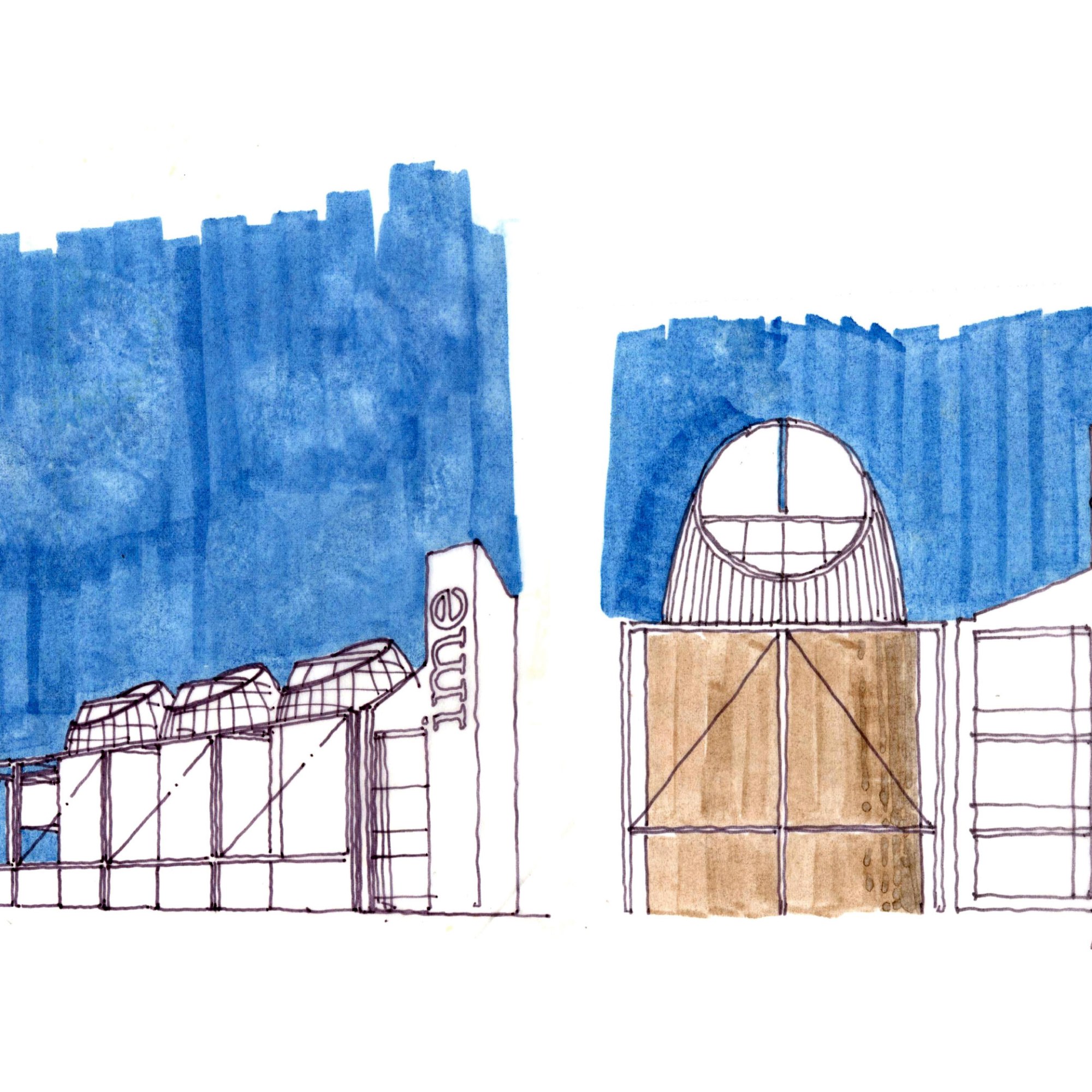

If we are successful at that, if we are able to make a project that then brings that to bear […] for me the BIC is really the epitome of that because it was really fatuous. It was a project that we often thought that we should just give this up and get out while we still have a shirt on our back and in an office that we can still survive and make it out.

At the end of it, it brings together two things. Firstly, the ideal – what is the public space, what is it to be in public space, what is it to feel public? And secondly, the incredibly challenging circumstances under which the building was made. How do you bring both those conditions to make something of value? I think great architecture does not come from a napkin sketch or from a sketch that I made. It comes from this negotiation that is often fraught and that is often kicking and screaming through the process.

<49:16>

SK: It is important for partners to identify each other’s strengths and collaborate so that the practice can survive. All the values of the practice and the way we want to run the practice also has to be rational at all points of time. To bring to bear schedules, budgets […] and if projects cannot be done on time then it is a tough way to run the practice. To keep that in mind, in the centre of everything is also very important.

Our biggest testament would be all our clients coming back to us, then we know that we have delivered and that they are happy, and they want to come back to us again for a second round. That has been most of our practice all these years. Most of our clients are coming back to us which says a lot.

CONTEXT

<51:53>

–

<52.33>

SK : A bunch of us in Bengaluru have gotten together to try and speak about and share our experiences of how some things are being done much better in each of our practices and bring that out to the group.

We hope that once we establish some ground rules, we would be able to share those with the younger lot who are setting up practices. We could help people set up practices and run it in a much more organised fashion than trying to figure it out over a long stretch of time.

To give back and to bring the experience to board, I am a co-founder of a women’s networking, support and mentorship group called WiREnet, which is Women in Real Estate. That takes a little bit of time and involvement to give back and to help younger professionals in the industry find their footing. I am a co-founder again of Avaza Concierge Service, which is a lifestyle concierge service for senior citizens in Bengaluru right now. So yes, that whole crazy hat about starting whatever you are passionate about.

<53:53>

BR: Looking at Bengaluru, we are incredibly fortunate to be working in this ecosystem, one that has been shaped by practices like Architecture Paradigm and others. Paradigm is a key practice in the city for doing the kind of work that they did at a time when that was not a common thing at all. […] Nagaraj Vastarey also did some really important projects. The other set of people who are really important to me personally are Soumitro Ghosh and Rajesh Renganathan. We talk about range; for range, you have to look at Soumitro and Nisha’s practice over the past thirty-five years. […] We look up to Rajesh because I would like to believe that we copy him shamelessly and copy their work and their grace and the quality of their proportions. Rajesh and Iype manage to distil their buildings down to the core essence of their beautiful plans.

I will also speak a little bit about practices such as yours, Ruturaj (Studio Matter). You and Maanasi have produced something that is so unique in the country. To do architecture work but also all of these other things; to find time to go out there and listen to the country. What is going on, what is the state of affairs? There are bunch of these practices who are also operating very differently from the way that we practice. Kerala of course is on another level. With a small practice, just reinventing ways in which to manoeuvre, Compartment S4, Sensing Local, Lijo John Mathew and Madhushitha CA at Cochin Creative Collective, another incredible young practice that is just reinventing not only the mode of operation but also what architectural representation look likes. What is it to imagine what architecture is? It is just groundbreaking.

There is a lot going on in the country, it suddenly seems to be bursting as it seams with creative energy.

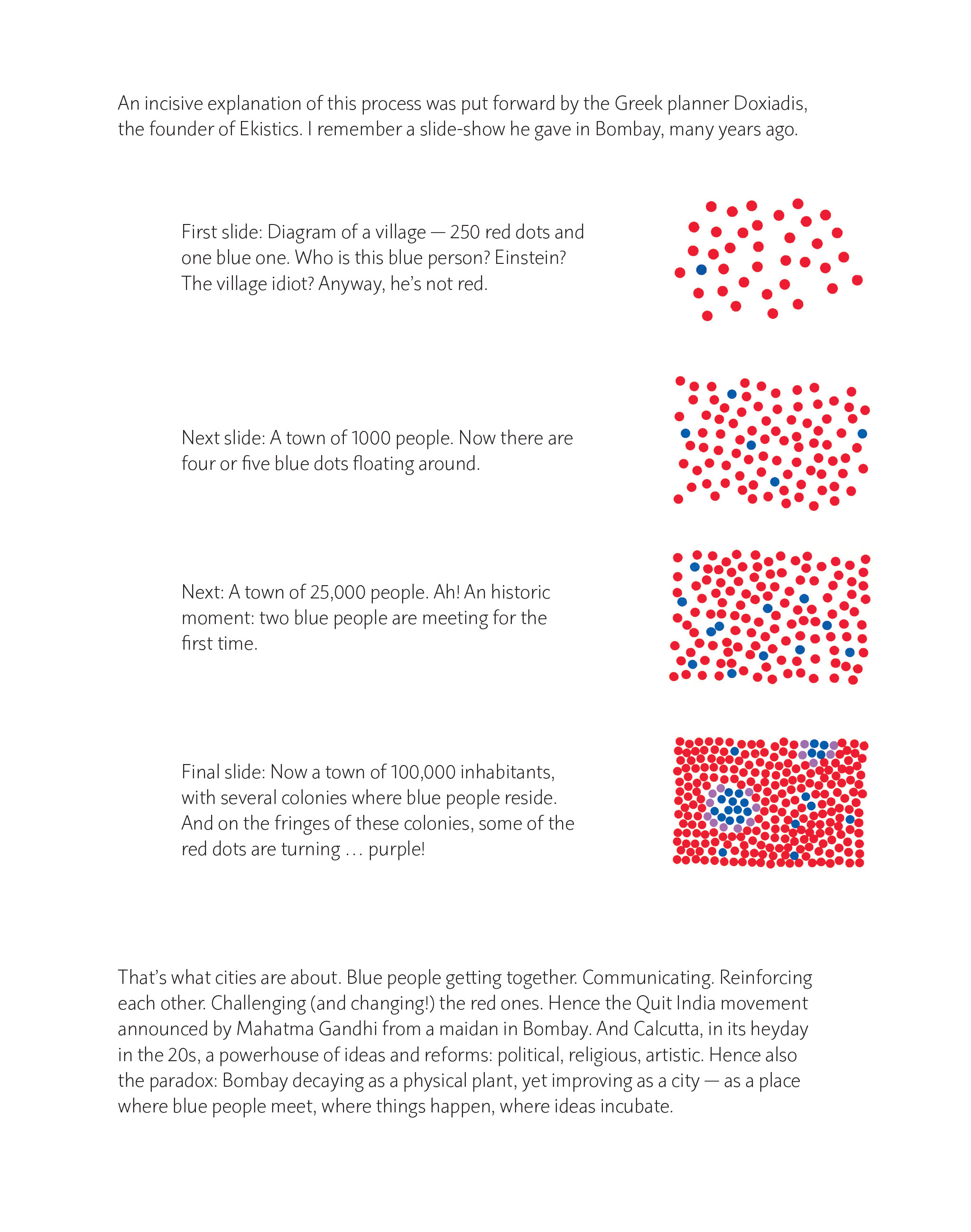

It reminds me of the diagram that Correa shows in his lectures of Doxiades’s orange and blue dots and that because we are all now crunched up together, the strange blue guys or the strange orange guys are creating little purples and then there is going to be more of these crazies doing funky stuff.

Drawings and Images: Courtesy Hundredhands

Filming: Vcams, Bengaluru

Editing: Gasper D’souza, White Brick Post Studio

Praxis is editorially positioned as a survey of contemporary practices in India, with a particular emphasis on the principles of practice, the structure of its processes, and the challenges it is rooted in. The focus is on firms whose span of work has committed to advancing specific alignments and has matured, over the course of the last decade. Through discussions on the different trajectories that the featured practices have adopted, the intent is to foreground a larger conversation on how the model of a studio is evolving in the context of India. It aims to unpack the contents, systems that organise the thinking in a practice.

The second phase of the PRAXIS initiative features established practices in the domain of contemporary architecture in India.

Praxis is an editorial project by Matter in partnership with Şişecam Flat Glass.