An editorial project by Matter in partnership with Şişecam Flat Glass, PRAXIS investigates the work and positions of diverse contemporary architecture practices in India. Featuring Sriram Ganapathi and Siddarth Money, the discussion circles the formation, ethos and outlook of the Chennai-based practice, KSM Architecture. Incepted in 1990 by K S Money, the legacy spanning three decades is embedded in design engineering, rigorous material exploration, and the art of building. Their works range across typologies, cater to varied programmes and demonstrate scalability, resourcefulness and energy efficiency.

EXCERPTS FROM THE INTERVIEW:

SG: Sriram Ganapathi

SM: Siddarth Money

FOUNDATIONS

<00:44>

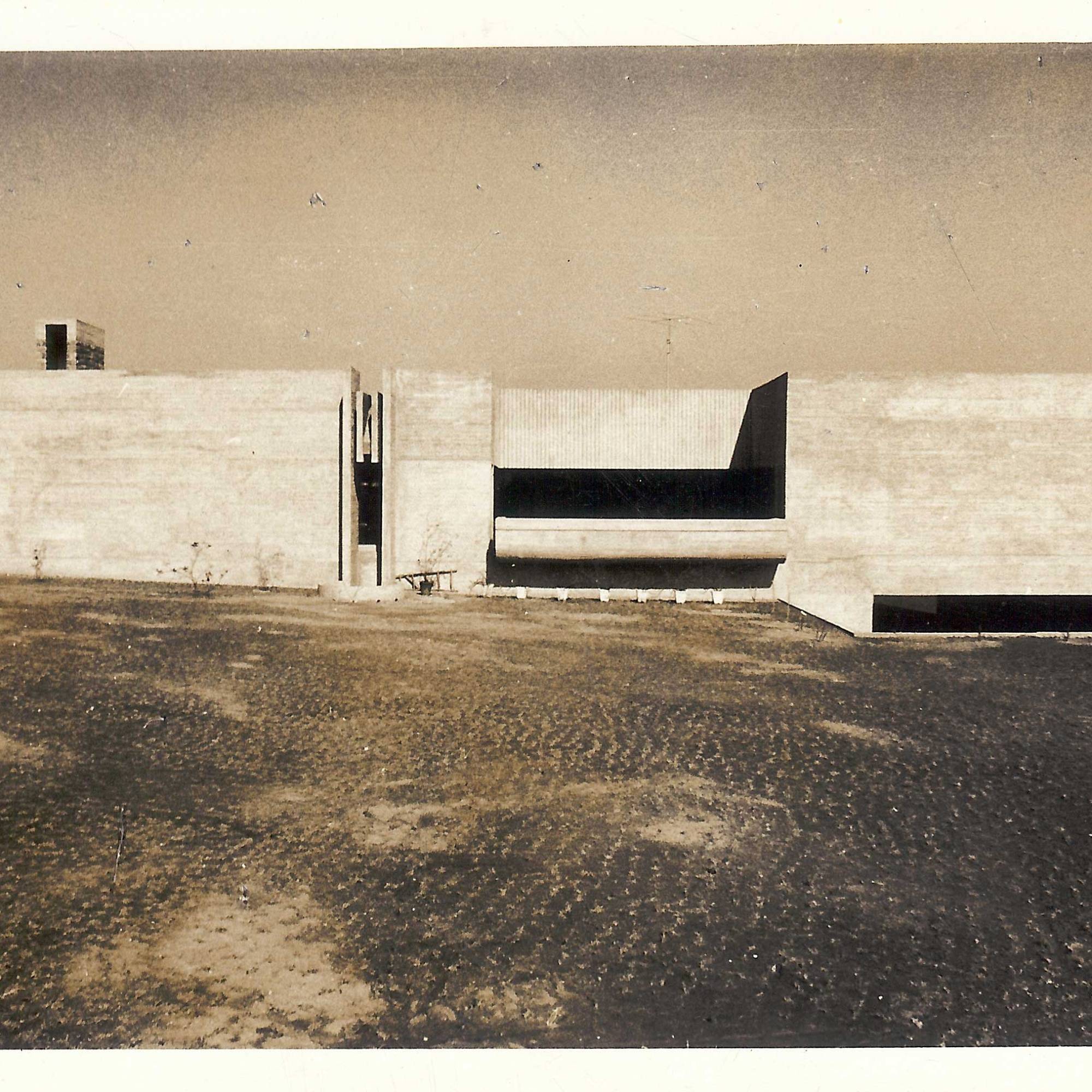

SG: As per the book, December 5th, 1990, is when KSM Architecture was formulated. It was started by K S Money, Siddarth’s father, who is a graduate of A C College of Technology (now Anna University), Guindy. His first major project was the Czechoslovakian Embassy, in Delhi. A Czech architect gave the concepts with whom K S Money worked as a site architect for three years. The building had exposed concrete walls and ceilings around 1966; our exposed concrete roof at the current studio is a legacy of what Money had done in his first project. […]

In 1990 he started the firm. January 5th or 6th 1991, was when I met him for the first time. My background at that point was that I studied architecture at the University of Roorkee (now IIT Roorkee), straight after which I went to work at B V Doshi’s office, Sangath which at the time was SDB – Stein, Doshi and Bhalla. I started my career there. After about a year and a half, I moved to Chennai. I was working at Nataraj and Venkat Architects for a short while when I met Money and felt that I needed to change and work on some international projects. […]

<3:20>

SG: After meeting Money, I thought it was a good idea to work for a couple of years and then I would go abroad. Money, at the age of forty-five, set up this firm not really knowing how things are going to pan out. He said that we will give it a shot and see how the practice works. […]

Money was really good, he knew exactly how to build, what the material was, and how you handle material […] The engineering side of it, air conditioning and electrical, he knew how to make things work and put a building together. I really enjoyed that time.

<05:46>

SG: KSM has always had a strong engineering side for knowing how to build. We take care of the design, but we also need to know that whatever we design needs to be executed.

<06:03>

SG: Having worked with Doshi, we were always thinking about climate and environment, and the fact that the environment needs to be looked at very seriously became a very strong agenda in our architecture. Those days these new-fangled words were not there, but we were looking at how it can be more energy efficient, and bring in air and light in our design.

That is how we were beginning to build an ethos and started doing work that was a little more meaningful and different from the general style of work that is seen in Chennai. We began to get clients who liked our work and a little bit of modernist thinking and a minimalistic approach to design started taking route in Chennai, and our projects were quite varied from industrial to institutional work. We were also doing a lot of residential projects as it had gotten in big time. However, we tried to make a difference in most projects in some way or the other.

<9:32>

SG: We really knew what we were building. Whenever we designed something, the intention was that we have to be able to build this. We need to execute it to whatever the terms are; if there is a financial or a material constraint, we work with that.

More than what the requirements really are, what we bring to the table is the key; the end user is the most important part. How is it that we get that feel, and sense of space, and how does a person feel comfortable?

<10:24>

SM: As a child, when he (K S Money) would bring drawings home; big pieces of paper for a kid, with all sorts of lines drawn over, is like a dream. […] I used to emulate, imitate and act like a child who was an architect and subconsciously, I ended up entering the field. I do not think it was a conscious decision ever to be an architect, I have always imagined that is what I was going to do and that is what I ended up doing. I wrote the entrance exam for getting into college, and got into CEPT.

There was a journey there, learning from a different perspective of how to perceive architecture from many of the greats who were teaching there at that point in time. From there on, I came back and worked for a couple of years at KSM, and then went and did my Master’s in Glasgow. I came back in 2008 and continued the journey here.

CULTURE

<16:01>

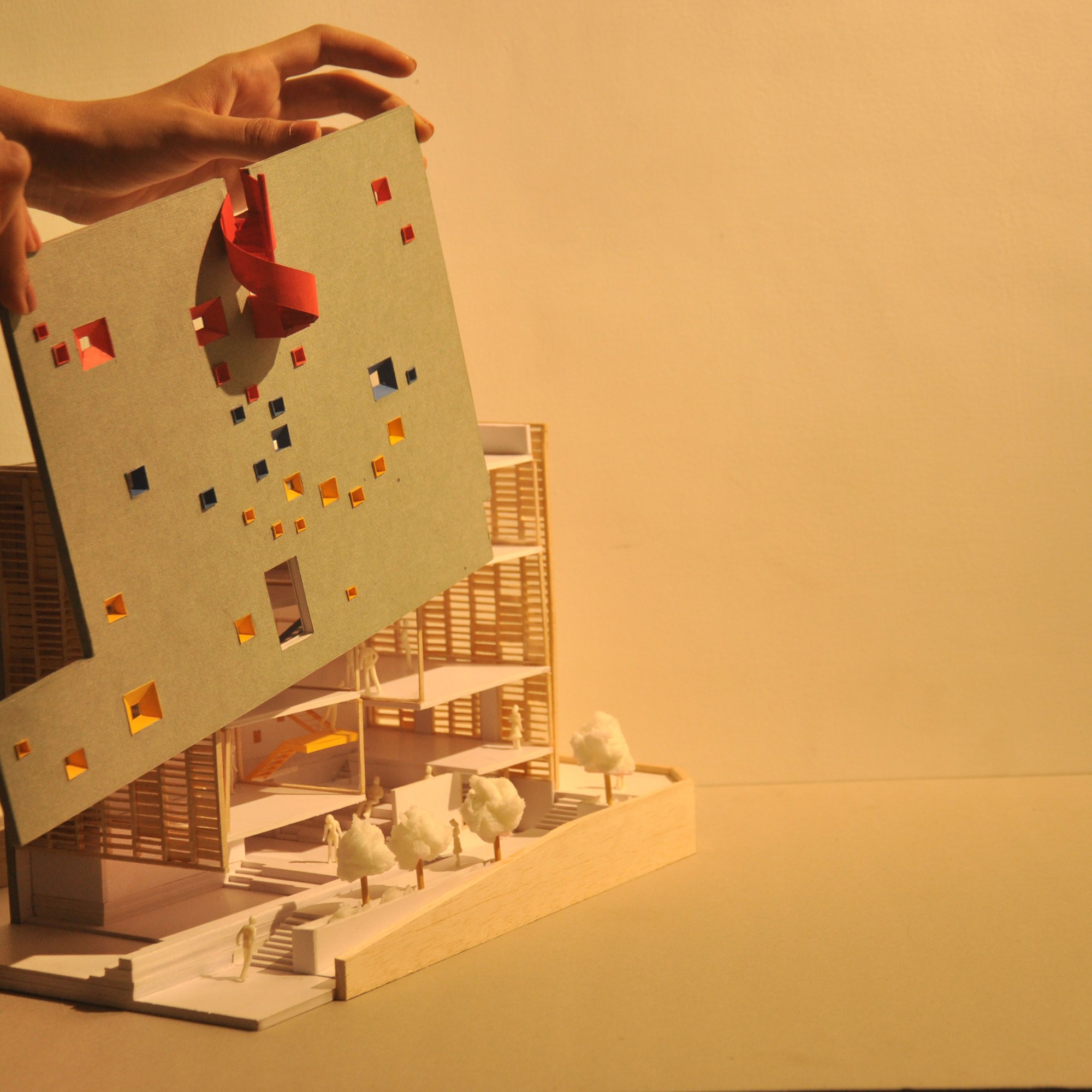

SG: We work very closely with each other when designing; it is not very individualistic, it is collaborative. When the first sketch happens, somebody else comes and sketches over it and the team gets in. Sometimes the engineers start early, sometimes it is the design development, and sometimes there is a little bit of research that we bring back. We are still open to change; the design gets evolved with everybody getting involved at that one stage.

When I say everybody, Siddarth and I will be involved, and then depending on who we feel is free to handle this project, we start. There might be discussions with somebody else coming in and giving their input. The ideation is then set and the core team of who is going to handle this project is picked. We are also flexible in that, we have two or three people working on two or three projects. So, a sense of redundancy is there but at the same time there is a level of flexibility for anyone to switch roles and move from one project to another.

PROCESS

<18:00>

SM: During the process of designing and conceptualisation all the way till documentation, we are in full control of what is going on. There is a sense of ownership all the way till the end but then suddenly, all of us face it as architects, you have now made this wonderful package and given it off to somebody and said “banaao” and it is now out of your control.

We like to have a sense of control even during the execution stage.

[…] We have the knowledge and experience level and we also have the technical backing to say that we can do it. If there is a way in which we need to tweak it, modify it, or adapt to site conditions or issues, we have a solution for it so that it is not going to be detrimental to the overall design flow, it is complimenting it or altering it lightly. […]

My father was all about the art of building, we are still keeping that half strong while the design half is also equally strong.

<20:25>

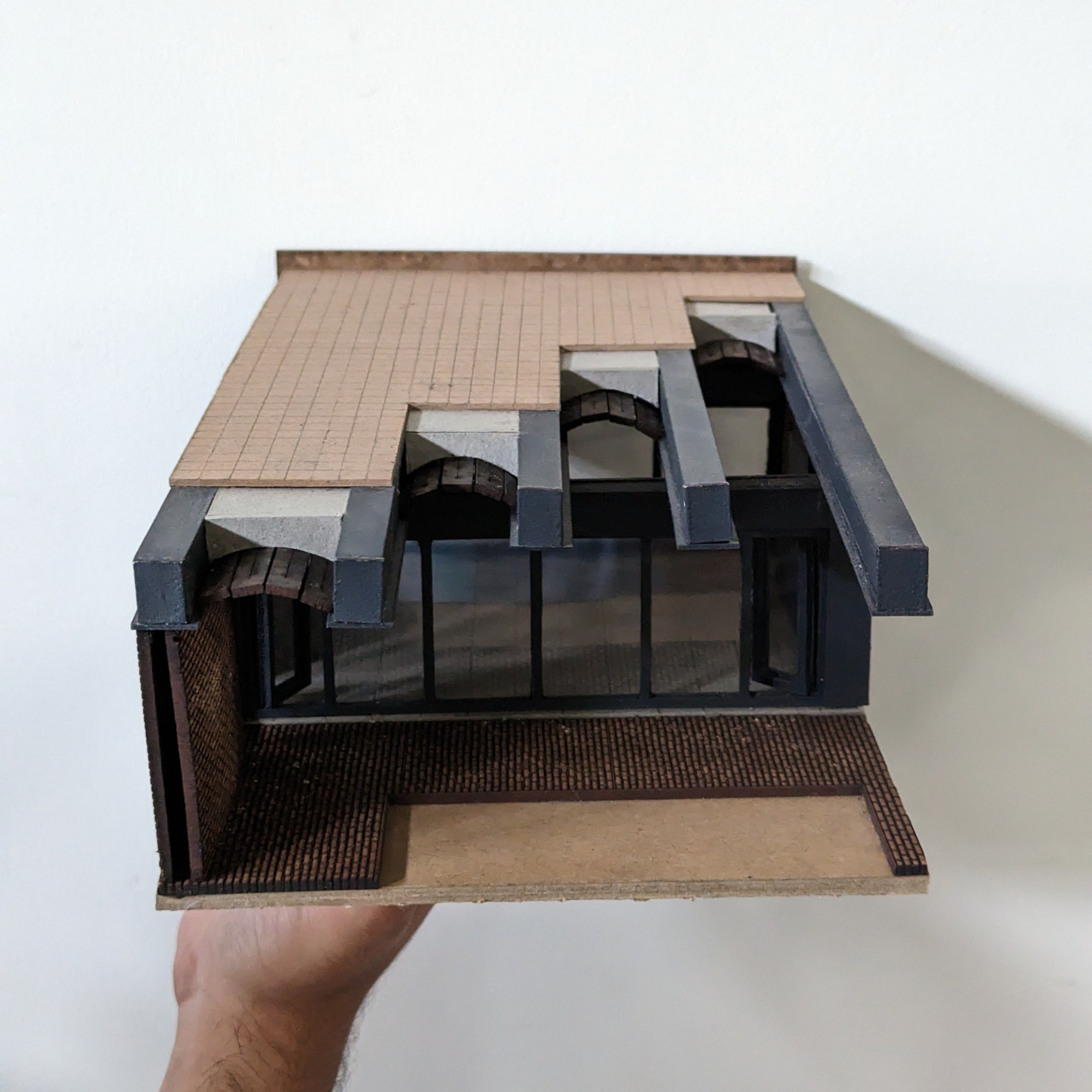

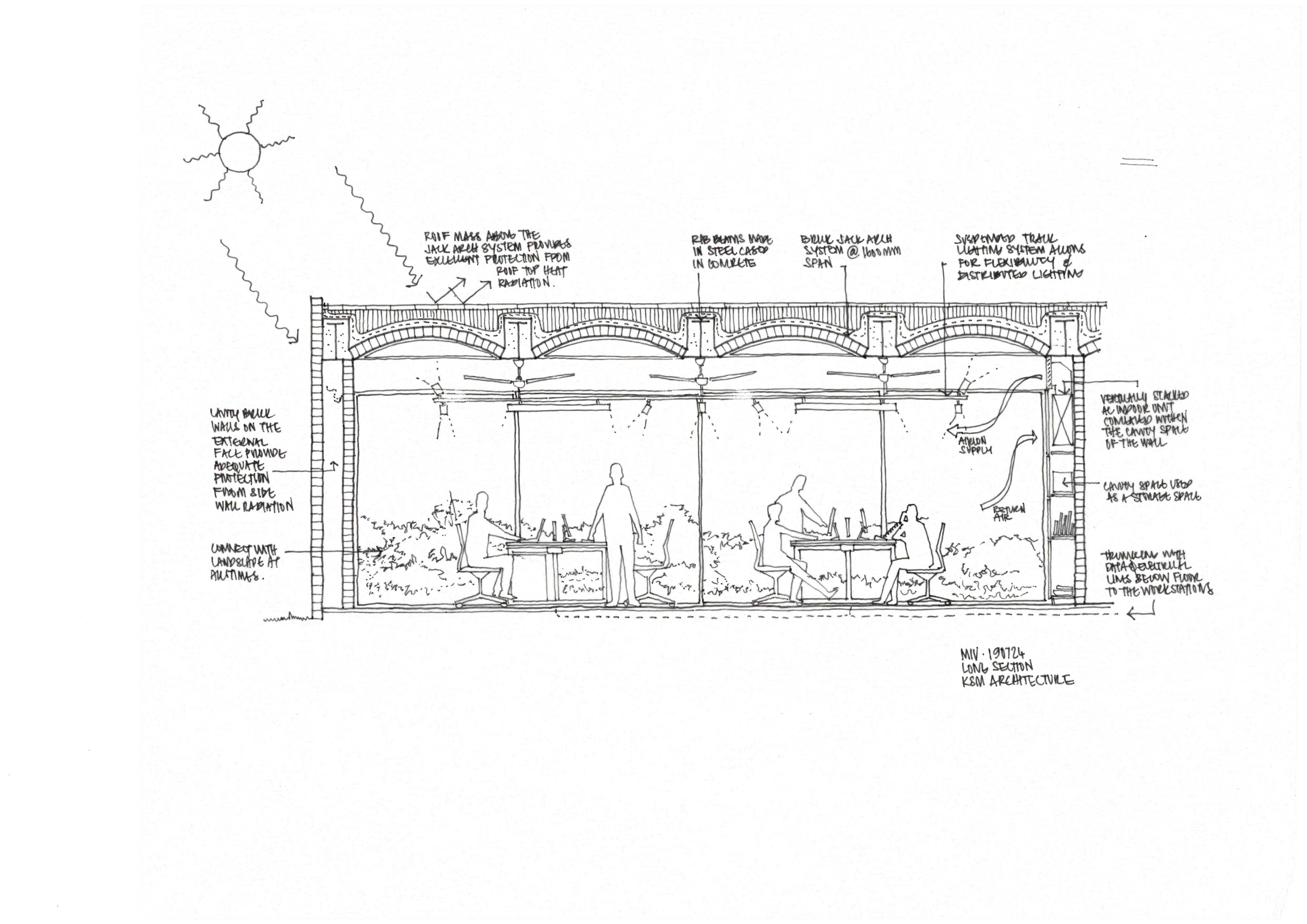

SG: If you look at the kind of work we have done in the last three decades, we have worked with brick, red brick, fly ash; different kinds of stone — granite, sandstone, limestone; concrete blocks, concrete of different kinds— glass fibre reinforced concrete, reinforced concrete, precast, cast in-situ. How do we create a low maintenance building in a very corrosive atmosphere?

Our learning is constant to the extent that if you do not want a bird to roost in your building, we have figured out the minimum dimension that our jaali should be so that the bird cannot sit and roost over there. The details and research on that is done by our engineering team coming up with solutions. We mock it up, make samples, and do these little studies before and estimate the costs so that when we present it to the client, we are very sure of how we want to execute it, what it is going to cost, how much time it is going to take and what will be the modality.

<23:15>

SG: Scalability is something we have always been wary of. We also believe that we can do very large projects to very small projects with the same level of facility that we can give. That is something we have trained ourselves in handling. We like to have a mix. In a year, we will look at a couple of large projects, the medium-sized projects will be the most in terms of numbers and then we have the small.

There will be small projects, and they will be interesting projects, but we do not say no to small projects. We do not say no to any project based on the size, we say that based on the kind of fun we will have in doing all of them together. […]

<26:21>

SM: When you choose large projects, from a design perspective, our focus has always been on passive environmental design, for example, in industry projects, the impact is on a huge number of people, about four hundred to five hundred or a thousand staff who work in a production unit where the general working conditions are mediocre to average […] It is not great, especially in our climatic conditions, these people are really working very hard. If we can make a ten percent difference to a genre like that, it makes a meaningful impact versus when you compare a similar impact to a house for four, there is a multiplication of the impact.

Similarly, if you take a school or an institution, the children always think back at those days in school […] it is something that will always remain in their mind, hopefully.[…]

The reach is greater when the typology is more public, is on a larger scale and has a greater impact on a larger cross-section of the population. Whereas, in residential, it becomes a close group. That has its own challenges in itself but, we try to let the thinking permeate under all various genres to see what we are able to learn, as feedback and as understanding from the various typologies.

<28:30>

SG: The quality of the space, what it does to the person inside, in the form of light, the feel that you have and the material […] I am keeping the whole environment approach away from it because for us now, that is a given, whether the client asks for it or not, we work out a model in such a way that we do not even talk about it anymore, there would be an energy-efficient module that would come out of the project.

<28:57>

SM: Now, more than ever, there is a greater restraint required in the choice of material, how much material to use, and how much waste are you generating out of this whole process. Most of our buildings, I would say, have no frills. In building, architecture, design, and in thinking, we do not want to add anything extra. It is what it is; it is a really lean and developed entity.

That frugality was something that when we heard Doshi say in the documentary – it had a profound impact; it is something that we resonate with in a lot of our thinking whenever we do our designs.

Let us not add something for the sake of adding things.

<35:21>

SG: We also believe that landscape plays a very important role, we try to see what is it that we can do. We try to learn much more about landscape and see how to engage it.

Many times in our projects, the landscape is more important than your building. At some point in time, the building is going to be covered and you are not going to see the rest of it. What is left then, is the experience that the architecture leaves behind in which the landscape plays a very important part.

<34:26>

SM: Before we built and moved into this office, our workspace was in a commercial building, we were in two floors and it was a perfectly good office but obviously there is an X-factor that is missing, to which the architecture is lending, and we are able to enjoy from here. This space definitely contributes to the way we run the practice – we have a lot of fun, and there is a lot of banter going around, the energy is really good. […] Coming to work feels really invigorating, there is always something exciting to look forward to.

CONTEXT

<39:12>

<38:03>

SM: It is such a diverse nation. We have similar festivals but celebrated differently, similar ingredients but cooked differently, and architecture is very similar.

We are all of the same land culturally and socially but have all moved into different tangents. Architecture is like that right now, mushrooming in multiple tangents, there are different people experimenting on different fronts with a lot of thinking going on regionally or with specific cultures or site requirements.

This is such a spectrum which is very hard to find in one country anywhere else in the world, where you have this cross-section where you cut it top to bottom, and there is not one layer that will be the same, it is impossible.

<45:43>

SG: In 2007, almost sixteen years ago now, Chennai Architecture Foundation started, and we have slowed down since the lockdown. Essentially, we have a very nice bunch of people, and we meet often.

The intention was that we do something for the city, for the profession of architecture, and for education of course. These are three agenda points that Chennai Architecture Foundation has gotten – it is a very loosely-held thing. Pramod Balakrishnan is one of the core members and a very active person who is always pushing us; there is A Srivathsan who is mentoring the whole process we have; and architectureRED (Biju Kuriakose and Kishore Panikkar), Mahesh Radhakrishnan, Pradeep Varma, and Raja Shyam Sundar (PT Krishnan). These are the core members who are looking at it and there is a fair amount of collective wisdom that is there.

We are hoping that we should be able to do far more work in these three parts, especially for Chennai, for Tamil Nadu, and take it forward so that it will help young practitioners, architectural education as well as the city in itself.

Images and Drawings: © KSM Architecture

Filming: Perf Studios

Editing: Gasper D’souza, White Brick Post Studio