Ashoke Chatterjee

A Recorded Lecture from FRAME Conclave 2019: Modern Heritage

In this lecture, Ashoke Chatterjee talks about the inception of the National Institute of Design in Ahmedabad, its formative years, the pedagogy provided to the students, the experiments with the curriculum, the challenges, successes, and failures it faced in becoming the ‘world-class’ institute it sought out to be today.

Edited Transcript

I am delighted to have this opportunity to be back in Goa after forty-one years. The last time I came here, it was to assist the Government of Goa with a study of its ‘carrying capacity’ for tourism: how would Goa manage the growth of tourism in coming years? This might mean tough decisions of planning and control. I need not tell you that my report was trashed long before the Hall of Nations. Goa is clearly still struggling with those issues, but it is good to be back. I am grateful to the organizers, to FRAME Conclave for inviting me.

Let me start by indicating that this talk will be a very personal view of one part of contemporary Indian design history. It will focus on the experience of one institution, the National Institute of Design, its educators, and those who studied there. It will cover some years of a larger institutional history as well as design in modern India. Yet NID has been a catalyst, so it is valid to draw on an experience which has been unique not only in India but in a global context.

There are other stories that also need to be told. Not just of other design institutions, but also perhaps the stories of the architectural institutions, the engineering colleges, and the schools of fine arts, many of them established well before NID and all of which have contributed to the story of Indian design and design education. Strangely, in the years that I have worked with the design community, we have never used terms like Modernism and Modernity that are now common in academia. Perhaps they were always there as concepts, yet what engaged us was contemporary problem-solving – problems that were inherited from the past and those that were new. For us, to be modern was to be relevant: to know what priorities faced society, to work with others to intelligently analyze these issues, and to find what we could possibly do through the design process to resolve any of them. So, the use of the word ‘modern’ and particularly terms like Modernism is not something with which I have much experience. The scholars here may need to pardon my ignorance.

My experience is with an experiment which was one of the first of its kind anywhere in the world, and it involved the building of the National Institute of Design in Ahmedabad. I will divide this story into decades, what each of those decades may have taught us and I will speculate briefly on where we might be now. The early years of design education were very tough. A critical reason was because the word ‘design’ was understood by most Indians to mean either engineering or fine arts, and occasionally, architecture. Industrial design was none of these. Somewhere in between, it was an animal which few could recognize. The story of the NID and its experiment is thus one of addressing a situation of almost total ignorance, of trying to create awareness of a new post-war profession, of advocating the relevance of this unknown profession to the tasks of nation-building in India, and of the need to test design over and over again in one central space: the marketplace for Indian products and services at home and overseas. The marketplace was where our values were to be tested and demonstrated. The marketplace was also where for many years an NID student either passed or failed. This was the prime benchmark of success: whether you as a student had understood a client’s need and as a student were able to address that need with a degree of credibility that could enable you to leave NID, not just as a graduate, but as a young professional, with a body of work to prove that you had the competence to stand on your own feet in the real world. Within this experiment, there have been any number of challenges, difficulties, barriers, and failures. And successes as well. Within success, also perhaps, the seeds of destruction that we are witnessing today and which others here have spoken about.

[05:58] Throughout this story, there may be two threads that you can hang onto. One is architecture. NID did not teach architecture. Although an original intention was that it would. It did not. The School of Architecture came up in Ahmedabad. Despite this, the earliest projects at NID had a lot of architecture in them, and many of those who taught at NID came from that profession. Many of the things that we did at NID were within the framework of architecture as you will soon see.

The other thread is exhibition design. You just saw Ram Rahman’s reference to the classic exhibition on Jawaharlal Nehru and His India, and as Ram mentioned, that is where NID began, where many of India’s first design teachers were trained, working on the job under the creative genuine of Charles and Ray Eames to create that exhibition, which then became world famous. Here architecture, every discipline of design, fine art, and craft all came together in an extraordinary way, demonstrating design education as essentially inter-disciplinary, hands-on teamwork. This marriage between products and media remains critical today.

My personal journey is neither as a designer nor as a design teacher. I have had the privilege to be at NID and to lead it for many years, not as a designer but as a member of a design team. My career began in an engineering industry in Calcutta. In those years, the term design in industry meant engineering design, even as the company I worked in was actually into industrial design as we now understand it. Yet the term then was product development. Years later, I went to work overseas, in Washington. That was where my experience with NID began, at that exhibition which Ram just showed, when it arrived in Washington in 1965 after opening to great acclaim in New York. The Indian community in Washington was asked to help with all that had to be done. That is how I met Charles and Ray Eames. They became friends, yet I never anticipated that one day I would be part of the Ahmedabad institution they were talking about in distant Washington DC, about this extraordinary experiment that was taking place in Ahmedabad, an experiment which they believed had global significance.

I would also like to return to the term design, which as I told you, was a cause of much confusion in those early years. The challenge was to teach design as a new profession in India, in a country with an unbroken history of design going back thousands of years. Yet, there is no word in any of our myriad languages that quite captures design as the industrial profession that NID was entrusted to bring to this country. So, you can understand the confusion we once had to survive. We had to use a term that did not make sense immediately, one that did not have an equivalent in any of our languages. There is a story about that.

One of my experiences in NID was a sharp rap on the knuckles from the Hindi Committee of Parliament I was warned that “You will immediately stop calling yourself the Rashtriya Design Sansthan” and you will instead use a proper Hindi word”. We struggled with dictionaries and scholars. When we tried to call ourselves the ‘Rashtriya Kala Sansthan‘, after consultation with some very wise people, we got an even ruder letter. This time from the Lalit Kala Akademi housed in one of the buildings that Ram’s dad designed. The message was, “We do not know what you blighters do there in Ahmedabad, but kala you are not, and you will stop using this term immediately”. To the Akademi, only fine arts could qualify as kala!

[09:52] Terms apart, what we did know right from the beginning was that this was a value-based profession. Values were at stake then as they are today. A value-based profession in which the issue is not aesthetics for its own sake, not a personal statement. Instead, your personal inspiration is valid only if it helps somebody else to resolve her problem. So, the student designer at NID had to learn that her first task was to care for others and to see the world through others’ eyes. Tradition and modernity became resources for both problem-analysis and problem-solving. And in this, the profession, the education, and the pedagogical system we were trying to build did have an incredible legacy upon which to draw.

One could go back to those 5,000 years. There is no time here to attempt a design history of India. But the legacy to which we were immediately connected in public understanding was the recent history of the art and engineering schools in India, the colonial period that came with that history and then the real beginning of contemporary design in India through the freedom movement, a period witnessing two World Wars, and the influence of leaders who may have never used the term ‘design’ yet whose instincts enabled NID to come into being. We are only now beginning to understand and appreciate this inheritance. At Gurudev Rabindranath Tagore’s Visva Bharati, in 1919, the Silpa-Sadana was established. The very same year Walter Gropius established the Bauhaus in Germany, both institutions reflecting a vision of a humane future, removed from war and colonial domination, within which usefulness, beauty and craftsmanship could respond to societal needs. Tagore visited the Weimar in 1921 and took a deep interest in the Bauhaus’ search for new ways of living. At Silpa-Sadana, extraordinary experiments in design would begin under his watchful eye.

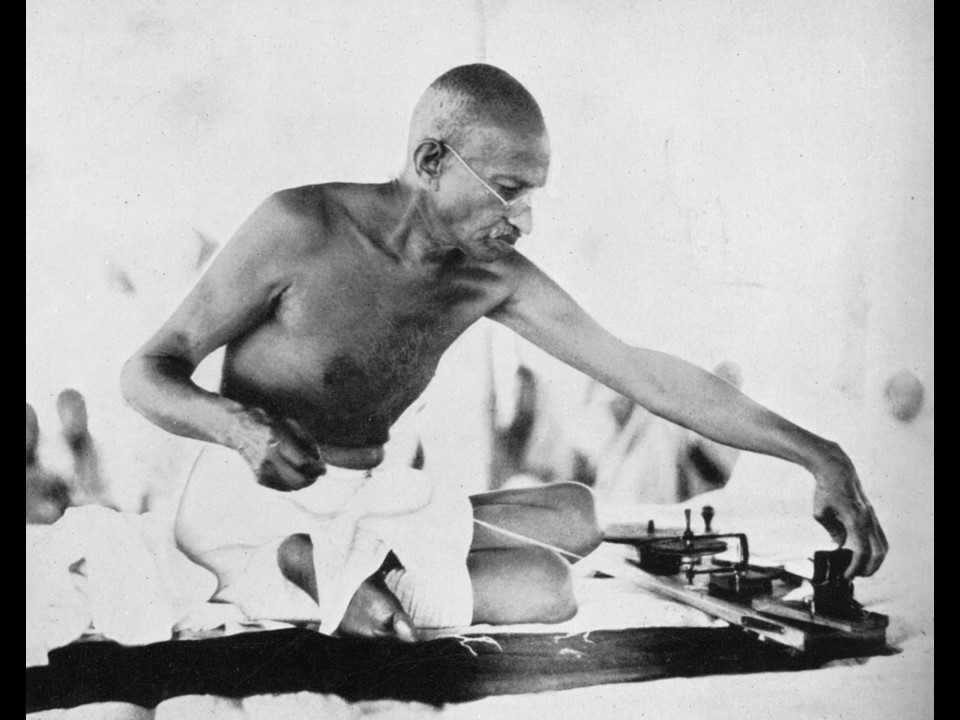

We have Tagore making India’s first connection with the Bauhaus, and then we have Gandhiji, who was a designer par excellence and who perhaps gave India and the world the greatest design story of the 20th century: the handloom revolution, and the Swadeshi movement. There is then the influence of two World Wars. In other parts of the world, the oxygen of the design profession is market competition. India for many years was a highly protected economy. Market competition, the lifeblood of design elsewhere in the world, was not a driving factor at home. At the setting up of the National Institute of Design, the driving force was nation-building, not building competitive strength. Design as nation-building was something new to the world.

The impact of World Wars, particularly World War 2, was to give an impetus to the consumer goods industry in India and to other industries like communication, printing, and advertising. To these, the design movement would later be closely linked. First a few examples of free India’s design inheritance.

This (referring to image 01) was a hundred years ago at Visva-Bharati. Take a look at the table and the chair. What do they tell you?

Gandhiji and Swaraj; here he is working on a portable spinning wheel (referring to image 02), which he himself designed so that he could carry it with him easily, particularly on trains and into jails. This is a floor chair that he designed (referring to image 03).

Now take a great leap forward. Freedom comes and with it the tragedy of Partition. Partition was perhaps the most important catalyst for what was to follow in Indian design.

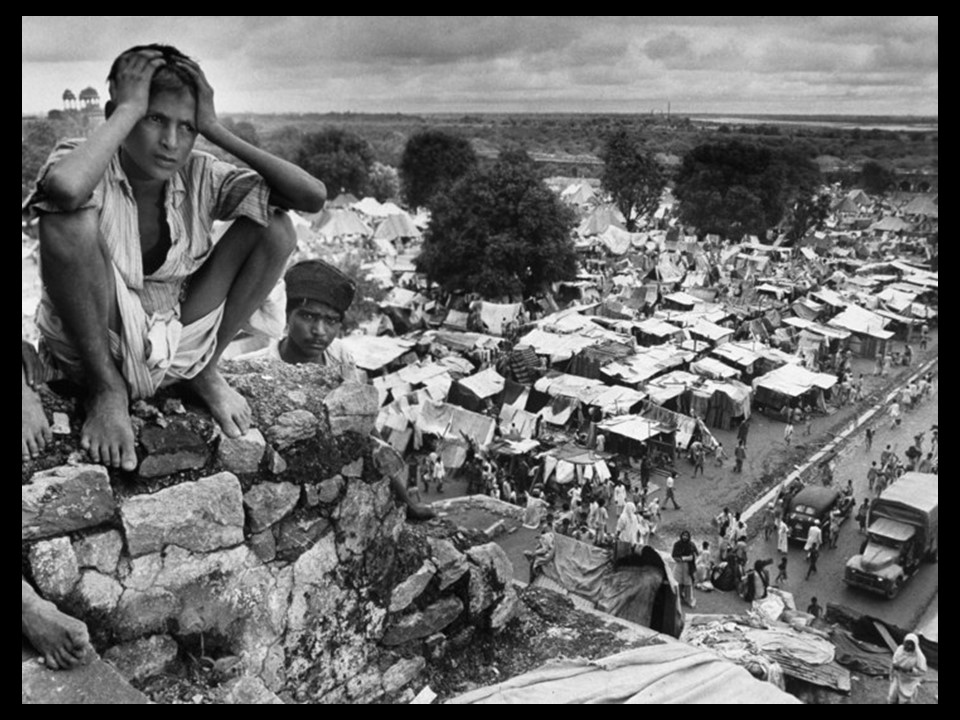

[15:08] The first challenge of Partition was to care for thousands moving in from East Bengal and from West Punjab into a new India. What was to be done? In Delhi’s Purana Qila, refugee camps had been set up. Nehru in desperation turned to Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay, renowned for her work with communities, to do something, not just to keep these hands and minds busy, but to restore sanity to people who had seen what no human being should have to endure. Sanity first, and then the need for livelihood as a key to healing and dignity.

Kamaladevi walked into the Purana Qila with needle, thread and cloth. She asked the women huddled there to make something. Not just anything, but to make something that reminded them of the homes they had lost, to make something that gave them hope for the future. Among the first products that emerged were embroidered phulkaris. These embroidered phulkaris would then have to be sold, and that was the beginning of the Central Cottage Industry Emporium on Janpath. And CCIE or ‘Cottage’ then became the catalyst for the pioneering designers of this country, some of whom Ram has mentioned. As at Santiniketan and at the Bauhaus, craftsmanship was here a door toward a better tomorrow.

One image is of the tragedy (referring to image 05) and of Purana Qila (referring to image 06) where Kamaladevi was asked by Jawaharlalji to ‘do something’. This conversation leads (referring to image 08) to the creation of Central Cottage Industries. On the left is Nehru at a new Vigyan Bhavan, and on the right he is (referring to image 08) at Cottage Industries with his sister, Mrs Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit, Mrs Prem Bery, and others who were the pioneers who set up that important store. It was to become a huge influence on contemporary Indian design history, as yet unrecorded. It soon became world-famous as a store and was also the place that would give opportunities to many of India’s design pioneers (referring to image 09).

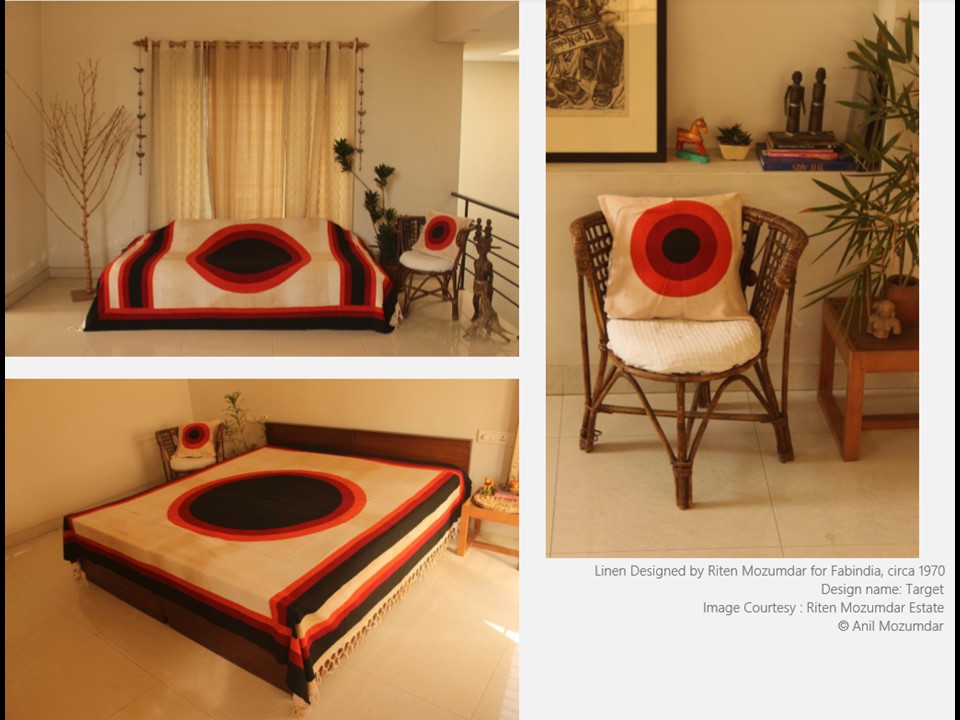

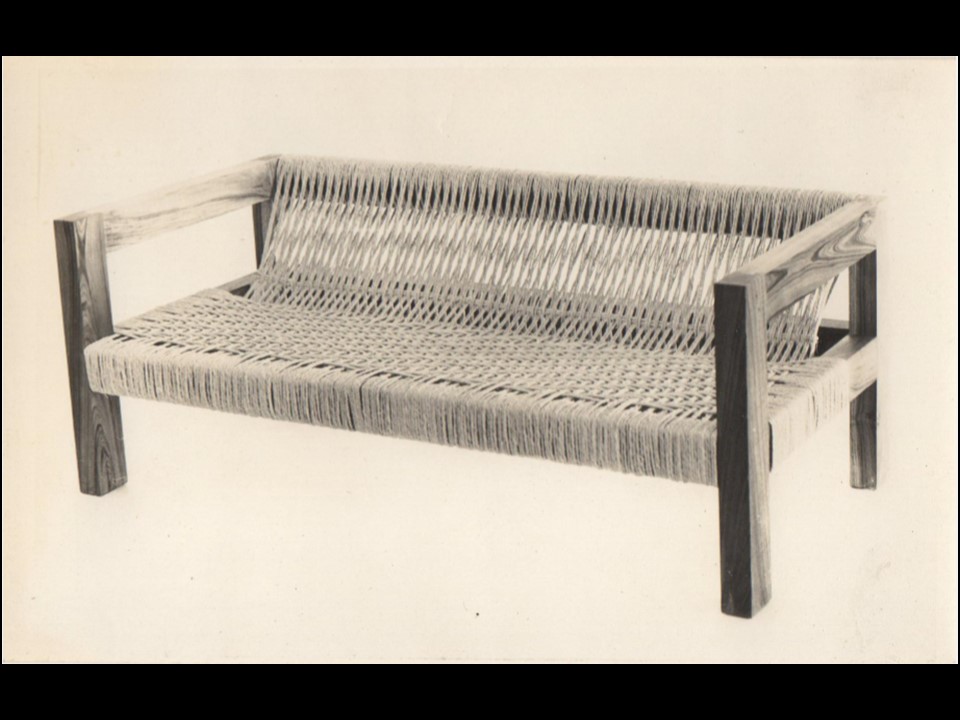

Sadly today the work of these pioneers is almost forgotten. Image 10 is the work of one of them, the late Riten Mozumdar. A product of Santiniketan, trained in Finland, and an icon of modern design. Riten Mozumdar worked with Mini Boga on her furniture range (referring to image 11). There is a movement to bring Riten’s work together so that his work is documented for the future. And there were many others – Mini Boga, Ravi Sikri, Ratna Fabri, Iola Basu, Shona Ray… the list goes on. Some of us are trying to save these resources so that these design histories remain for students to know and understand this period and its pioneers.

All this while, three people were thinking about the future of design in India. Perhaps many were, yet foremost among them were these three, Gautam Sarabhai, Gira Sarabhai, and the late Mrs Pupul Jayakar (referring to image 12) who with Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay, was the other great lady of Indian craft and design. They were there, watching, encouraging and thinking about what should be done to make design a force for nation-building.

Among others in Delhi at that time, was a journalist called Romesh Thapar (referring to image 13) who recently had moved to Delhi from Bombay. Romesh was one of the first and perhaps the greatest design thinker we have had in this country. As a journalist, and a thinker, he was conscious about design as a new discipline and what it could do to lift the quality of Indian life. The man on the right is Ravi J. Matthai (referring to image 14), at that time, setting up the Indian Institute of Management at Ahmedabad. Familiar with those who were creating NID, and interested in this talk about design as a discipline, Ravi Matthai was wondering where and how management and design might be able to come together in the future.

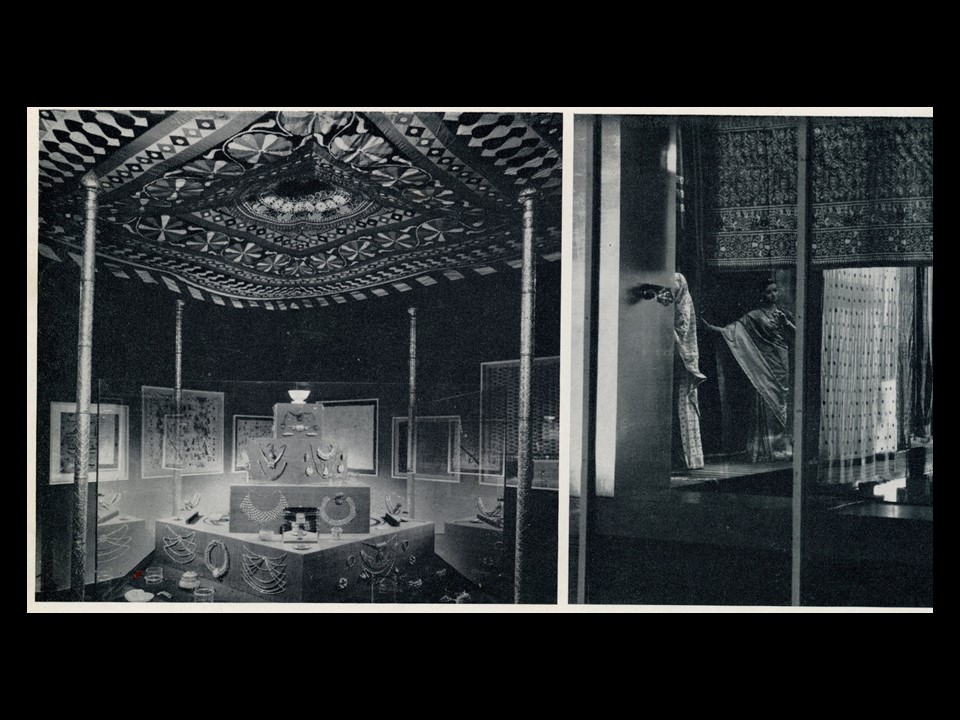

[20:17] Pupul Jayakar would emerge as a catalyst. She was active in the craft movement. In 1955, she was asked to take to New York the first expression of Indian cultural diplomacy. It was an exhibition called Textile and Ornamental Arts of India (referring to image 16), which was sent in 1955, to the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) in New York. The story of NID would begin there, once exhibition material arrived from New Delhi. Curator Alexander Girard, a famous textile designer, turned to his friends, Charles and Ray Eames in Los Angeles to come to New York and help him create the show (referring to images 17 and 18). Mrs Jayakar had arrived and together, they put up the extraordinary Textile and Ornamental Arts of India. The exhibition was not only the first expression of its kind. It was also important because it brought with it two great Indian artists, Shanta Rao (referring to image 19) and Ali Akbar Khan. It was also the occasion for Pather Panchali to have its first screening — the rough-cut flown from Calcutta to New York on a Pan Am flight even before Satyajit Ray had seen it. So this was no ordinary exhibition. In this setting, Charles Eames would ask Mrs Pupul Jayakar a startling question: “These products, these incredible textiles, and crafts that you have brought to New York, are they about India’s past, or are they about her future?”

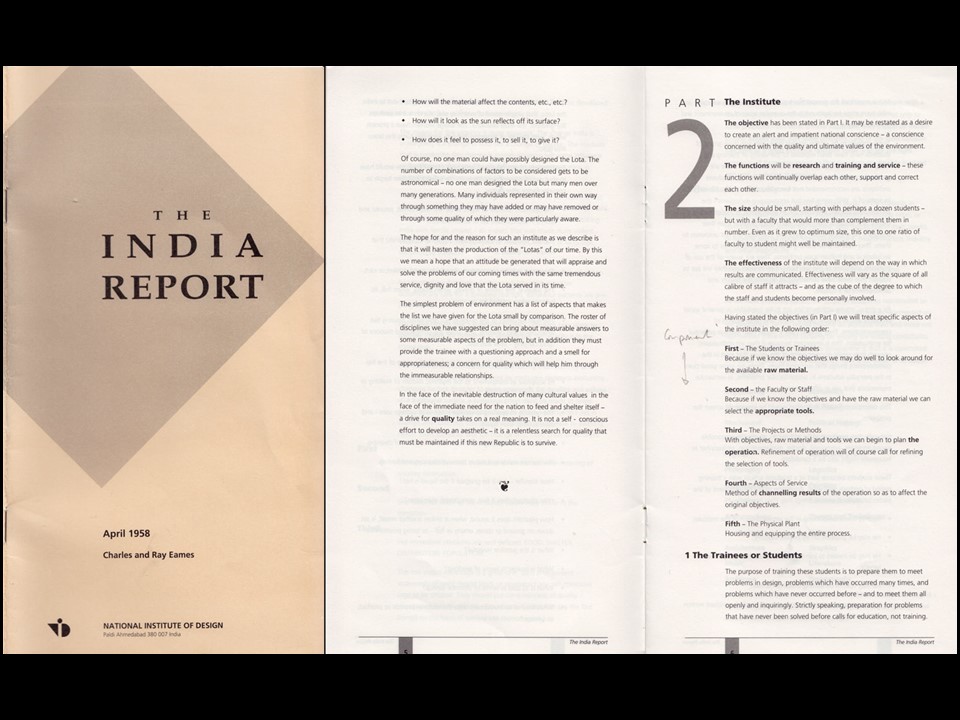

From that question emerged a conversation about transitions from tradition to modernity that Pupul Jayakar would report back to Panditji in Delhi. Soon an official invitation brought Charles Eames and his wife Ray to India a couple of years later, to survey small industries in the country. From that visit emerged the India Report (referring to image 22), today classic in design literature, and from that Report was born the National Institute of Design.

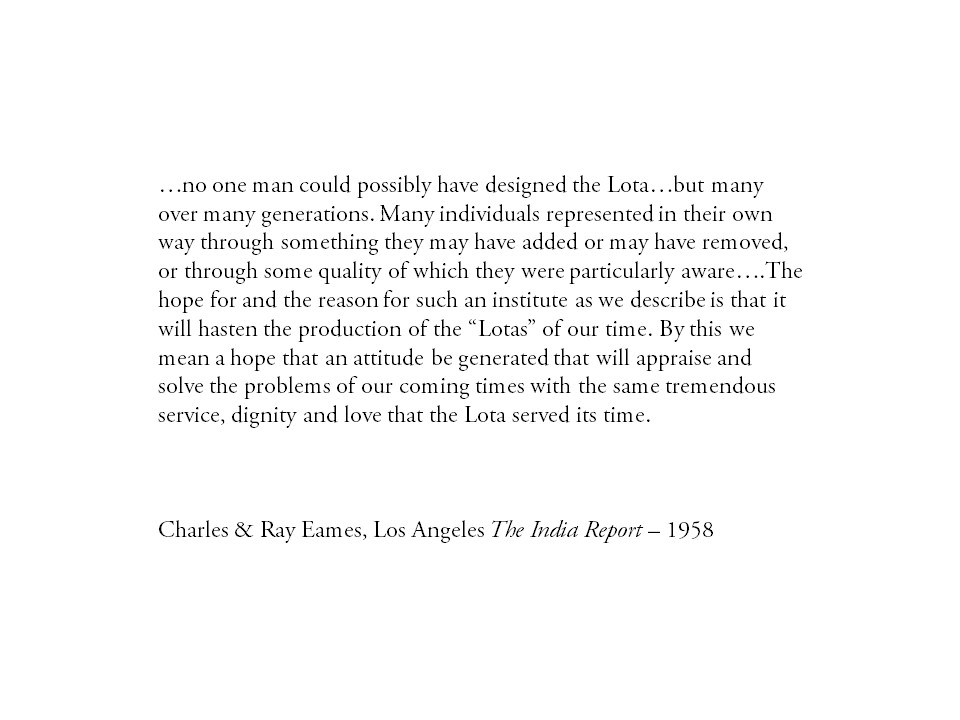

What was special about the India Report? It was in many ways a meditation on design. It was a speculation on what might change and what should not change in a new India. It provided no formula for change, yet it did ask important questions: on what basis will choices be made? Who will make essential choices of what must change and how? What new streams of knowledge may India now need in making its choices? Would India’s tradition of creative destruction be the path ahead, drawing on the past as it moves into the future? A symbol was used to represent design as a bridge and as a culture of care and service. That symbol was the lota (referring to image 23), which Charles and Ray Eames held up as perhaps the greatest example of industrial design that they had encountered. They then went on to analyze the lota and finally concluded that “The reason for and the hope for such an institution, as we suggest, is that it would produce the future lotas of India”. By this, they meant the products and systems that would serve India with the same “service, dignity, and love” that the lota had served India for countless generations.

Note carefully that the NID starts with this ethic of service, dignity, and love. Years later, I would ask Charles Eames about this on his last visit to India. Service and even dignity were easier to understand but where did love come into all this? Eames replied that love is the ability to see the world through somebody else’s eyes, and that is what design service should be all about: the ability to see the world through somebody else’s eyes, and with that, the capacity to help others to lift the quality of their everyday environments, to make our own worlds a better place. All these years later, those questions of India’s past and its future still remain, in a world now so much more complex. Images: Photograph of Shanta Rao by Herbert Matter (referring to image 19). Charles and Ray Eames in India (referring to image 20).

[25:10] The India Report (image 22) and the object, the lota, held up as a supreme symbol of industrial design (image 23). This quotation (referring to image 24) then became the value system for NID, a very difficult value system to live up to then and perhaps today more challenging than ever.

Looking back at NID’s history, the sixties were its founding years. That was when the Institute began. It was given a floor in Corbusier‘s museum building, created for the Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation. Planning started there, with Ahmedabad selected over other places — Hyderabad, Bangalore, and even Fatehpur Sikri were considered. It got to Ahmedabad because of the presence of Gautam and Gira Sarabhai and aggressive Gujarati entrepreneurship. Gira Sarabhai had just returned to India after practising with Frank Lloyd Wright in the USA. Her iconic NID building would come out of the ground on the banks of the Sabarmati River, recalling that apprenticeship. The first curriculum was developed with infrastructure based on the Eames Report ideas of what equipment and facilities would be needed, acquired with Ford Foundation support.

Charles Eames soon returned to India to train the first Indian cadre of design educators, working with them hands-on to create what would be the Jawaharlal Nehru exhibition. Later in that decade, there would be other exhibitions taking this experience further: the Montreal World Trade Fair, the New York World Trade Fair, Gandhi Darshan, and others. Through these opportunities, the first postgraduate programmes were introduced in product design, textiles, ceramics, and furniture.

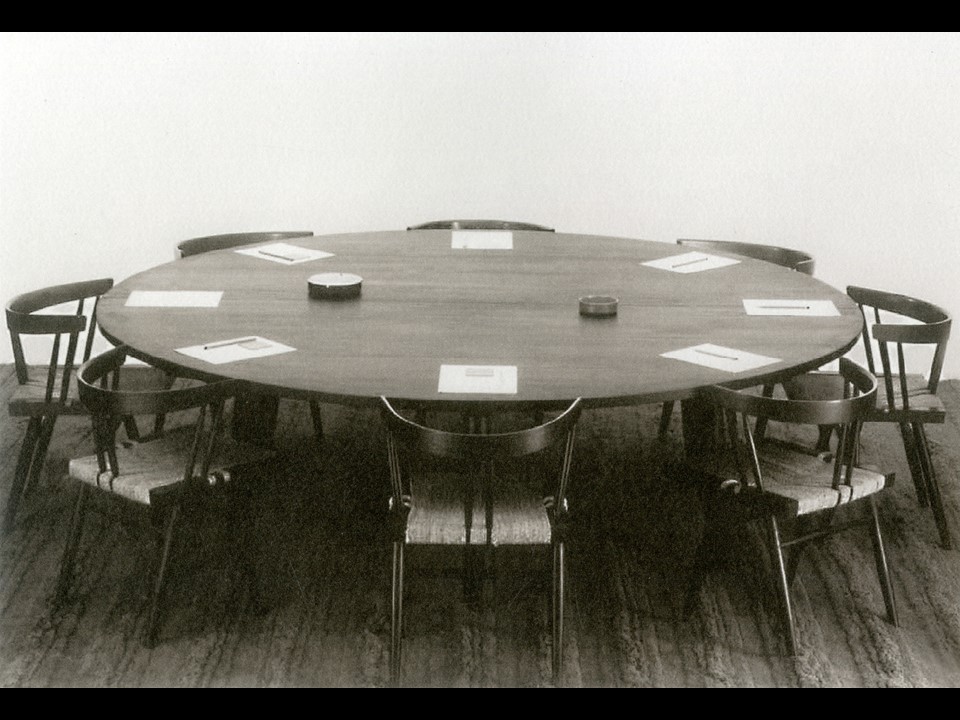

Challenges soon emerged. The first design teachers found that the young people coming into postgraduate studies were handicapped by an attitude of specialization and a resulting ‘tunnel vision’ which could inhibit inter-disciplinary teamwork and the stamina for both uncertainty and openness. The Institute then made a phenomenally important decision that design education had to start at the school-leaving level, something not attempted anywhere else in the world. While curriculum development was going on, professional practice moved into the Institute with apprenticeship as a non-negotiable core of design education. Students worked in studios and workshops on real-life assignments from marketplace clients, with their teachers as mentors who were themselves practising designers. The relationship between the educator and the student was that of practitioner and apprentice, a relationship graduating over time as co-creation, with service to the client as key to assessing the validity of any design option. Some of the important NID clients of that era were L&T, the Bhabha Atomic Research Centre, Cistronics and Cooper Engineering. With these professional assignments, design work began to flow out of NID into the Indian marketplace.

In the sixties, one finds that some of NID’s work was in fact architectural. Louis Khan came to NID to start the work on the IIM building. It was an NID project for IIMA, although Kahn initially believed he had been hired to create a design institute. A gentle correction came from Gautam and Gira were NID founders (referring to image 27).

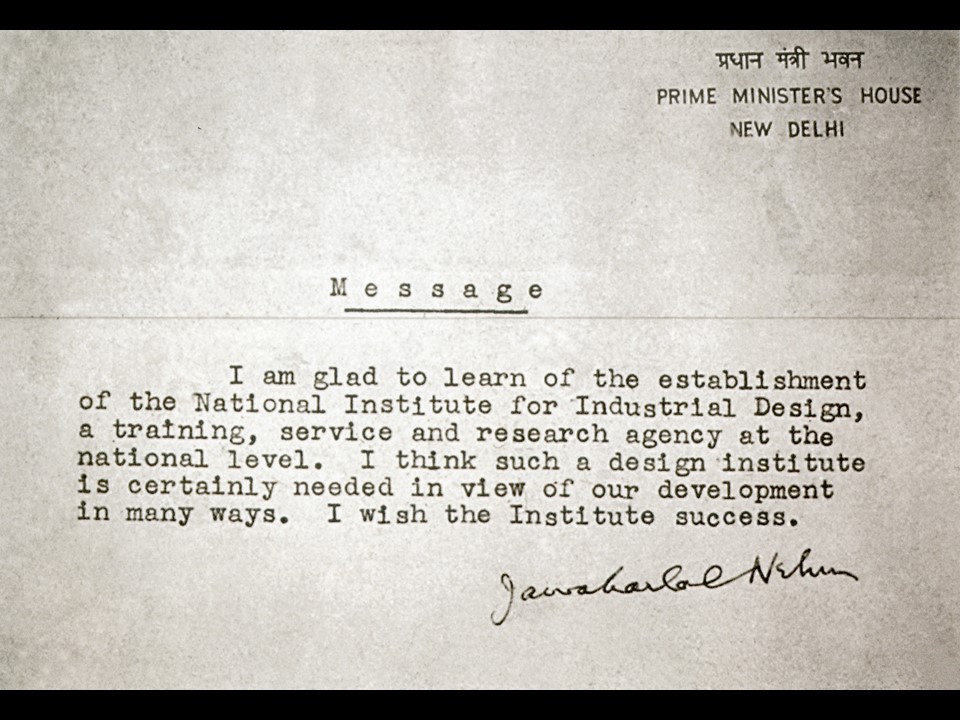

Jawaharlal Nehru sent a message of encouragement at NID’s founding, recalling no doubt his earlier conversations with Pupul Jayakar (referring to image 28).

In the sixties, great teachers laid the foundations for design learning. Among those who came was Nelly Sethna (referring to image 30), a weaver, whom Gira Sarabhai brought to NID. In turn, Nelly recommended that her batchmate at Cranbrook be brought to Ahmedabad: Helena Perheentupa of Helsinki (referring to image 31). Helena was to emerge as one of the greatest teachers at NID, crossing all the disciplines, doing a huge amount of work in the curriculum design, and remembered to this day as the greatest of mentors.

[30:21] Shona Ray, who would have much to do with Cottage Industries, is seen here with Kumar Vyas, hailed today as the father of Industrial Design education in India (referring to images 32 and 33).

Dashrath Patel, with Kumar Vyas, was among the first of the design teachers brought into this experiment by Gira and Gautam Sarabhai (referring to image 34).

An ‘Indian Bauhaus’ was the hope and dream of the NID community (referring to images 35 and 36) at that time. Coming out of the ground, the marriage of design education with architecture began with the design of NID’s building, reflecting Gira Sarabhai’s architectural expertise, her apprenticeship with Frank Lloyd Wright, with a major investment in structural research by the Structural Engineering Research Centre in Roorkee. (referring to image 37).

There was also a building in Bombay, one of the earliest projects (referring to image 38) intended not to train architects, but to give architects an opportunity to work on real-life projects which would provide professional experience of a kind still rare at the time.

Louis Kahn with B V Doshi are seen here at the start of the IIMA project (referring to image 39), while the Nehru Exhibition had begun its global journey (referring to images 40, 41, and 42).

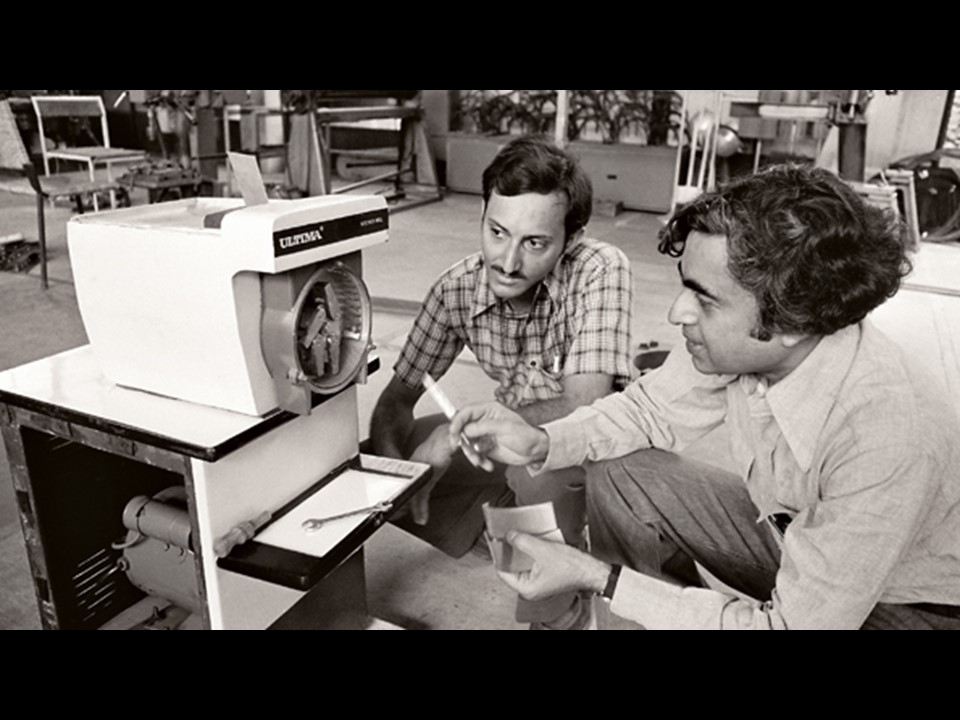

It may be important to recall that (referring to Image 43) to create this exhibition, NID needed to have workshops of the kind envisaged in the India Report. Thus workshops, classrooms, and studios at NID became completely integrated so that students could have access to workshops and studios twenty-four hours to be able to work on projects of the kind that were coming into NID, demanding the need to deliver client deadlines as well as output quality, and not just academic timetables.

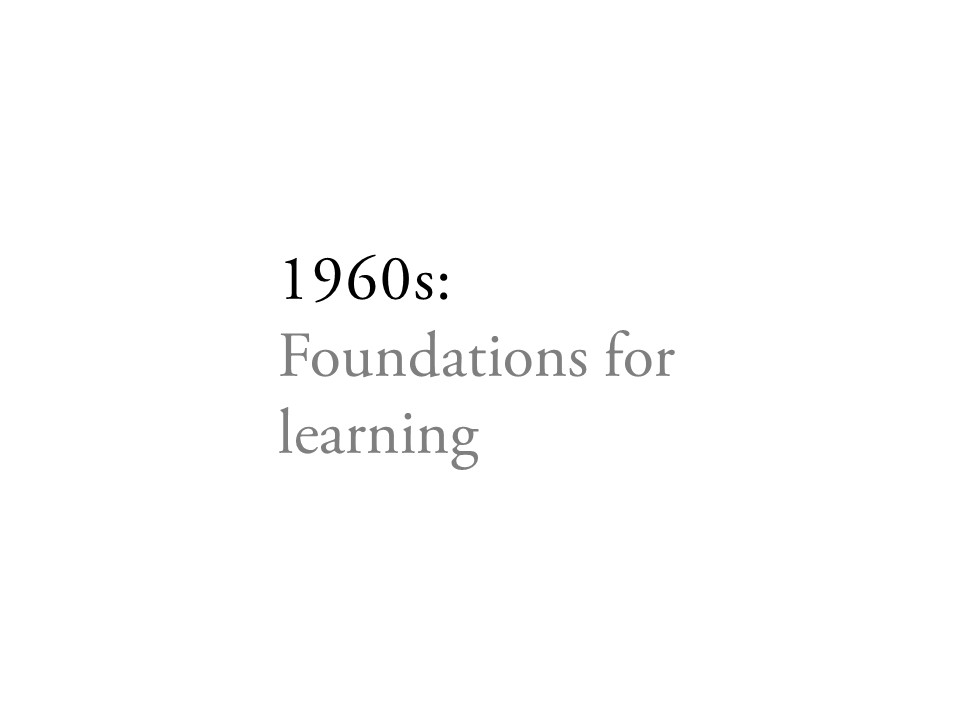

This was to become a part of the NID culture of learning by actually doing, a culture now threatened by the rush for numbers rather than an insistence on one-to-one apprenticeship (referring to image 44). Projects of the kind described become difficult if not impossible in the current situation of large numbers and an adherence to the ‘degree culture’ rather than learning by doing in the marketplace.

The Oxberry animation camera was among the wonderful equipment that came to NID through grants from the Ford Foundation (referring to image 45). These are among projects done for real-life clients (referring to images 46, 47, 48, and 49). They give an idea that by this time the NID was actually working with a range of industries, and every one of these involving students and teachers working together. Among the visiting mentors was the legendary furniture designer George Nakashima (referring to image 50) from the U.S.

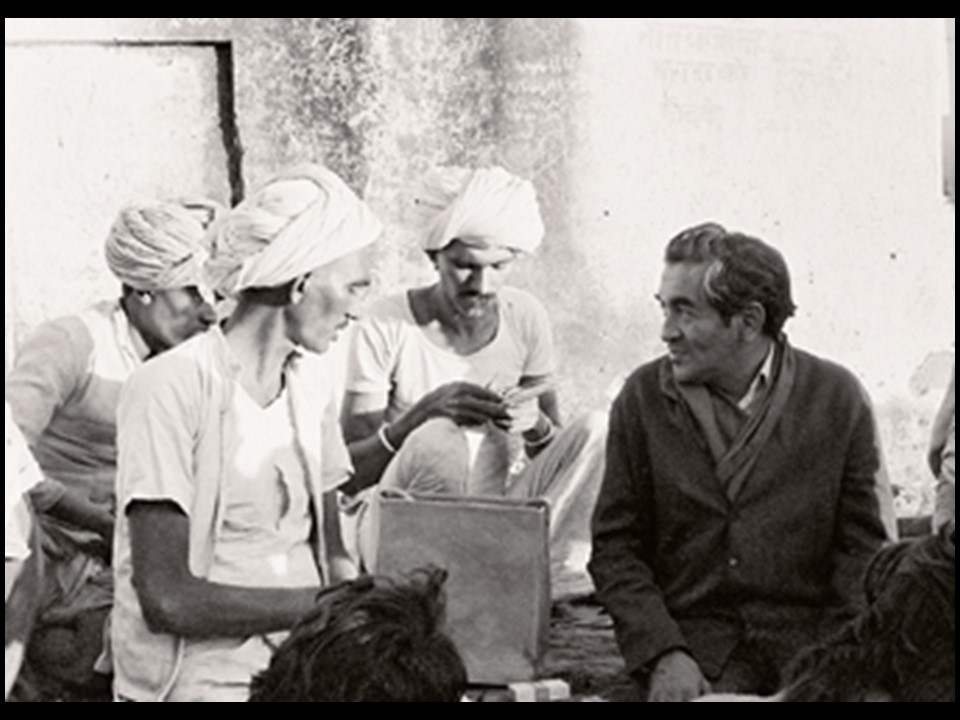

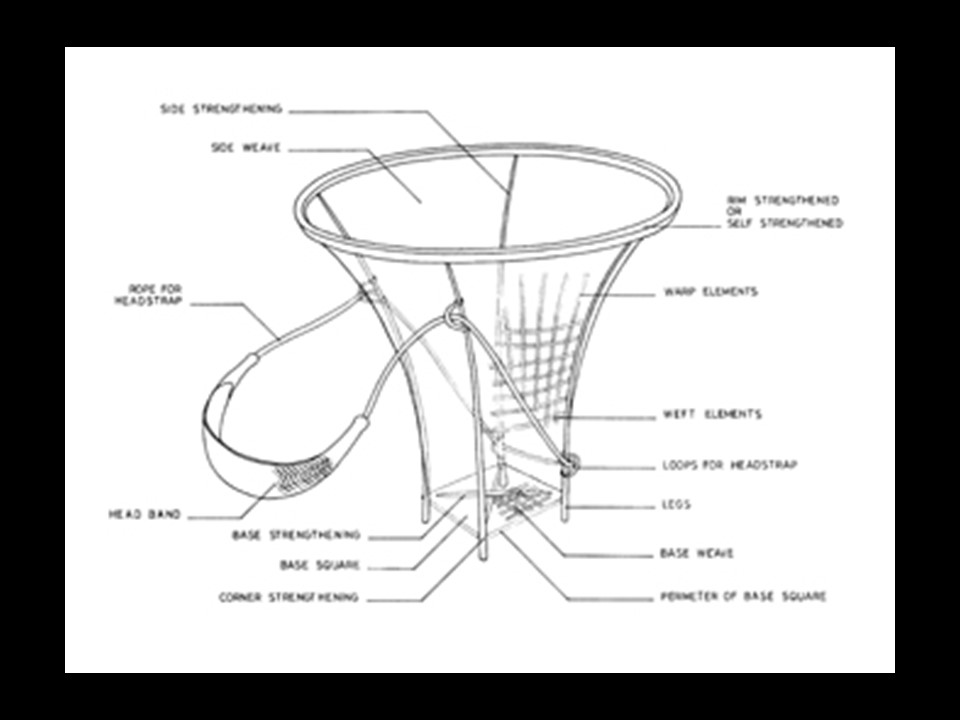

The first animation films were made on the Oxberry (referring to image 51). Ethnographic research started at NID, primarily in the craft sector (referring to image 52). Here, I might point out that the 1955 exhibition that went to New York, and the Nehru Exhibition which followed helped to establish hereditary crafts as a foundation for design sensitivity and knowledge, the ground in which Indian design could be rooted. That critical relationship (the bond with crafts, artisans and craftsmanship) remains essential, both at NID and through that early experience at all design schools in this country.

Graphic design, so essential to communication through the early exhibitions, produced at NID symbols that soon became part of India’s (referring to images 53 and 54) visual landscape, many of these symbols originating as student and faculty projects.

The seventies were a period of consolidation. The School Leavers Programme was started. By 1974, some NID faculty had moved out of NID and opened India’s second design school at the Indian Institute of Technology in Powai, the Industrial Design Centre which took user-centered industrial design education into the heart of engineering studies. During this period, interesting things were happening. Gautam Sarabhai wrote a seminal document called ‘National Institute of Design – Internal Organization, Structure and Culture’ to articulate what this new educational system was attempting and what this new profession required as its basis. Romesh Thapar wrote a paper for UNESCO – ‘A Design for Living, A Design for Development’ (referring to image 57). NID received the first international recognition for the quality of its work through the Philips organization and the International Council for Industrial Design (ICSID).

[35:36] Before that milestone, NID would have to endure an administrative crisis so severe that there were suggestions to close down the NID entirely. The Sarabhais left NID. What was to happen now, amidst all this negativity? Very few still understood an experience new not just to India but globally. Indira Gandhi was one of the few, supported in her office by H Y Sharada Prasad who had worked as editor on the Nehru exhibition. The Prime Minister asked Romesh Thapar “What happens now?”. Romesh Thapar put together a group of people (among them, Charles Correa, Gerson da Cunha and Sharada Prasad) to investigate the crisis and to suggest options for the future. Their Thapar Review Committee Report was a resounding affirmation of what NID was trying to do. The Committee protected the Institute and insisted that this Indian experiment in education should expand, grow, and spread. Thanks to Mrs Gandhi‘s understanding of what was at stake, the collective wisdom of the Thapar Committee, and Pupul Jayakar’s tenacious advocacy, NID survived. That is what brought me to NID in 1975.

With international recognition in the seventies, came an invitation from the United Nations to hold the first and so far, only United Nations conference on design at the NID campus. This was suggested in order that the design world come to India, understand a pedagogical experiment and the context within which it was unfolding, and test its relevance, not just to the developing world but to others as well. The UNIDO-ICSID-India 1979 Conference culminated in the Ahmedabad Declaration with its Major Recommendations; to this day the most convincing articulation of the role design can and should play in the global development process.

During this decade, all kinds of other things were happening. NID got a chance to work with the Indian Space Research Organisation’s seminal SITE experiment. A huge exhibition was held in the Hall of Nations at Pragati Maidan, Agri Expo 1979, mobilizing the entire Institute. The teaching of every discipline was done through one year of concentrated work at the Agri Expo. Every student (except freshers), and every teacher worked together with subject experts to communicate agriculture as India’s lifeline. Not just an exhibition on agriculture, but for NID an immersion into India’s largest industry, and its rural context.

At the same time, in the middle of the seventies, the first graduating batch was ready to emerge from NID. Would they get jobs? It may be recalled that India was a protected market with a limited understanding of design as a profession, with little competition as an incentive for design and in which copying from Western models was widespread. The first job offers came predictably from sectors where competition was already a force demanding creativity and innovation for survival and growth – exports, advertising, and handicrafts. With that foot in the door, placement became a major NID responsibility, taking design advocacy to every level of industry and into the social sector. The need was to test the relevance of the design process. An opportunity soon emerged, taking design educators and students into the realities of Indian poverty. ,

NID and IIMA under the leadership of Ravi Matthai moved into a desperate corner of Rajasthan for what was to be called the Rural University experiment. In Jawaja, the two institutions broke away from conventional clients to work instead with communities so deprived that some would be eating a square meal once every two days. Was there anything that managers and designers could share from their disciplines that could help this community to eat twice in one day, and to do so without dependency on outsiders? Perhaps even more important, what could these disciplines learn from traditional wisdom and experience that could enable them into the service of India’s vast majority? Although the movement to Jawaja was not intended as a craft experiment, but rather as one of education toward self-reliance, artisans and their crafts moved into the centre of this experiment as a resource for change. For almost fifty years we have been colleagues together, learning together, through different generations of teachers, students, and artisans. All that is another story. Yet it was underway when the world came to NID to understand India’s design efforts and the range of its concerns from space exploration at one end and the deprivation of poverty at the other. At the UNIDO/ICSID India 1979 conference on ‘Design for Development’, a culminating Ahmedabad Declaration for Design for Development has proved as a global landmark. Although the Declaration did not get as much traction in India, elsewhere in the world it did. Decades later there would be indicators from other parts of the world of the impact of the Ahmedabad Declaration as articulating the deepest aspirations within the design community. What remains particularly striking about the Declaration is that it was the outcome of reflections by designers – professionals, students, educators, and clients – coming together in India, stimulated by its diversity to think not just of one country but through it, to find relevance to the world. The Ahmedabad Declaration has within it the essence of the Sustainable Development Goals which decades later would be established by the United Nations as benchmarks for human progress. Looking back, the Declaration offers an example of the power of design as a way of understanding the world and of making it a better place, just as the Rural University experiment attempted to do in a corner of Rajasthan’s desert.

[41:11] This is the Jawaja block (referring to image 58). NID faculty and NID students (referring to images 59, and 60), working with the leather workers, and weavers of this region (referring to images 61 and 62).

As in all efforts for real change, the years at Jawaja have been full of problems, failures, as well as iconic products (referring to image 63), that have found their place in world markets. Yet the challenges of justice and opportunity continue in Jawaja as elsewhere, compounded by new realities of climate change, social and political conflict and changing aspirations. Perhaps here was the real learning for designers, recalling Romesh Thapar’s great essay ‘A Design for Living, A Design for Development’ – “But at the end of the day if the designer is going to do anything for three-quarters of the globe, we have to be able to lift people to a better quality of life and to dignity”. Back again, to Charles Eames and the ethic of service, dignity, and love – taking strength from a realization in one corner of the Rajasthan desert that design as a discipline and profession has within its power the ability to encourage change and to offer hope.

And in this area, is where the Bauhaus system had its most crucial test. I would say it is the most crucial test anywhere in the world because we were mocked when we went to Jawaja. ‘What are you guys going to do there with your fancy European ideas? You can do nothing. But that group, working with designers as equals, is today a thriving community, but still at the bottom of our social structure, but that is another long story.

The products they brought out (referring to images 64 and 65). The leather products and the rugs that you see here (referring to image 66) are designs created by the artisans from their own inspiration. And the first kick in the pants we got when these products came out was that they were referred to as Scandinavian designs. “It must be that Helena woman who has gone down and given them designs”, they said. The only one to support this whole thing was John Bissell of Fabindia. He said, “If that is what they are saying to you, that is the sign of your success because your artisans have a palette and they have a vision, which is as contemporary as anything that Europe can give.” So, that is the message for the artisans, and these designs have lasted for years, and that process is still going on.

[45:30] In the seventies, NID also moved into a partnership with architects in what would be India’s first experiments in Integrated Area Development Plans for places of archaeological and heritage importance. The first was Fatehpur Sikri (referring to image 67). That story is linked to architect Satish K Davar, who started this project and then died suddenly in London, leaving the Institute stranded with no access to any of his materials. Professor Kulbhushan Jain of the School of Architecture in Ahmedabad then came on board, and NID made this (referring to Image 68) a series of projects which soon moved into the national discourse on conservation, through central Ministries, INTACH (Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage) and other organizations.

At the same time, NID went to the north-east (referring to images 69, 70 and 71), working there with tribal communities in another incredible opportunity for students and teachers, leading to craft documentation models which have stood the test of time, pioneered by M P Ranjan and other pioneering scholars of design.

The 1980s brought profound change. Socialist India began its move into market-driven economics. A new era of liberalisation was symbolized by the Asian Games, colour television, the opening of markets to imports, growing competition and the acknowledgement of the power and indispensability of design in international trade. Fashion entered as a concept and practice, becoming the dominating image of design among aspiring youth. In that decade the term designer moved from a noun to an adjective and with that semantic move came perhaps the greatest challenge to the ethics and the values on which NID was founded: designer clothes, designer lifestyles, designer products with driving implications of style, affluence and profit. ‘Designer’ as a term, was no longer an evocation of service, but rather of affluence, style, and fashion. The arrival of the fashion industry encouraged new institutions of design education including the network across India of design schools established under the umbrella of the National Institute of Fashion Technology (NIFT) and a major emphasis on apparel in emerging curricula.

The eighties and nineties saw new design schools emerging all over the country. From two in the seventies, one would soon find over two hundred names, including such outstanding entrants as Srishti in Bengaluru, the Industrial Design Centre in Guwahati, and the Pearl Academy network. In 2014, an Act of Parliament declared NID as an institution of national importance that would henceforward grant degrees, not ‘mere’ diplomas. NID was given the mandate to spread out over the country. The pressure everywhere was to build the number of admissions and to enlarge the number of graduates in response to the Indian industry’s need to build its competitive strength at home and overseas. Few paused to ask where and how design teachers were to be built in this number-driven context, or how to sustain quality within the rust to numbers.

It should be kept in mind that NID’s journey as a design leader has so far taken place outside the conservative Ministry of Education. That Ministry with its University Grants Commission (UGC) could not tolerate NID’s open culture of learning by doing and demonstrating — no exams, no marks, no ranking. All this made NID heretics, yet heretics who had demonstrated (with the support of ministries of industry) that there was another way, that there was a mode of education that was an Indian response to the challenge of modernity, that was Indian on its own terms (in the tradition perhaps of Tagore and Gandhi), respected for its credibility by the global community. Today design education in India follows the norms established by the UGC, the very system from which NID had escaped in the sixties. What is to happen to ‘that’ quality of design education for which the world came to India in 1979? Can NID continue to attract brilliant designers who may never have finished school or university? Can it employ faculty who do not have a PhD but who can deliver design service of the highest global standard? Or who have not published yet have created, inspired and influenced India’s finest designers?

My last slide is the 2017 destruction overnight of the Hall of Nations (referring to images 72 and 73), to be replaced we are told by a convention centre of international standards. The Hall of Nations was evidence of Indian ingenuity in design and technology to create something unique, contemporary and Indian. It has now vanished as a symbol of modern India. Why? Perhaps because when we build and if what we build succeeds, then we have to show how clever we are by fixing what is not broken. By bringing things down, rather than improving what exists and learning from both success as well as from failure. And today in design education as in so many other domains, there is this terrible urge, as in the case of the Hall of Nations: this need to be seen as ‘world-class’. We are told today that design education in India must be ‘world-class.’

So, the question that I ask after forty years in this sector is, what was design education in India if it was not ‘world-class’, responding not only to India’s perceived needs but to those of the planet? The world came to India in 1979 because they saw India as a leader. Yesterday we were respected leaders. Today, in 2019, we are asked to follow others in the pursuit of ‘world-class’. Is there a message in that? ♦

Prof Ashoke Chatterjee received his education at Woodstock School (Mussoorie), St Stephen’s College and Miami University (Ohio). He has a background in the engineering industry, international civil service, India Tourism Development Corporation, and 25 years in the service of the National Institute of Design (Ahmedabad) where he was Executive Director, Senior Faculty, Distinguished Fellow, and Professor of Communication and Management. He has served a range of development institutions in India and overseas, particularly in the sectors of drinking water, sanitation, disability, livelihoods, and education as well as worked with artisans in many parts of the country. He was Hon President of the Crafts Council of India for over twenty years and continues to serve CCI. He lives in Ahmedabad with his son Keshav, daughter-in-law Prativa, and grandchildren Kabir and Alisa.

FRAME is an independent, biennial professional conclave on contemporary architecture in India curated by Matter and organised in partnership with H & R Johnson (India) and Takshila Educational Society. The intent of the conclave is to provoke thought on issues that are pertinent to pedagogy and practice of architecture in India. The first edition was organised on 16th, 17th and 18th August 2019.

Organisation and Curation: MATTER

Supported by: H & R Johnson (India) and Takshila Educational Society