An editorial project by Matter in partnership with Şişecam Flat Glass, PRAXIS investigates the work and positions of diverse contemporary architecture practices in India. Pooja Khairnar of the Nashik-based pk_iNCEPTiON speaks about a certain mutability of ideas holding deep personal and professional significance that travelled through time, experiences and cultures to shape ‘architecture’ for her. With careful definition and constant reflection, a vivid map of interactions with the city, meaningful dialogues with mentors, and self-introspective journey emerges to conceptually anchor and create a scaffolding for the studio’s growing body of work to be understood. The repertoire of projects thus created across scales demonstrate a sustained emphasis on multiple ways of cultivating cultural and aspirational exchange with communities, and on the notion of ‘expanding’ a brief based on a critical evaluation of what the project impacts and what is a ‘necessity’.

EXCERPTS FROM THE INTERVIEW:

PK: Pooja Khairnar

FOUNDATIONS

<00:00:30>

PK: My architecture journey began with an IQ test I did when I was in 12th standard. Before that, in my family this profession was very new to us. Because of that IQ test, we got introduced to the new course called ‘architecture’ and I got admitted into the college called MVPS’s Sharadchandraji Pawar College of Architecture, Nashik (CANS). The college was amazing. It had a beautiful culture of learning. […] We learned to be curious all the time, to ask lot of questions, to be consistently hardworking, to be observant, to move around, to look at things which are there in the context. Thus, the base was very interestingly formed.

One incident that left a lasting impression happened when I was in third year of college. Few of my classmates and I went on a documentation tour in Gujarat. While coming back we got caught in the Mumbai floods that had happened in 2005. We were stuck there for four days. We saw people drowning, we saw people suffering; we saw the bad condition of the city which was a very traumatising experience for me. When I came back, I decided that I am going to do something about this and do a thesis project on it. When I discussed this with people, I got to know that it was not actually a natural disaster, but a man-made disaster. And we as designers, at some points of time, are responsible for developing a city so unreasonably.

This incident stuck with me for so long that I designed a Tsunami Memorial in Chennai. Through my project, I tried to show that we can make people realise how natural disaster can be tackled by structural systems.

Can people remember, can my spaces give people the remembrance of what happened, what people have suffered and why we have to be very conscious about our context, sustainability and nature? I think at some point, sensibility started developing when I did the project.

Fortunately, the project got selected for Kurula Varkey Design Forum (KVDF) and I went to CEPT University to present in front of a jury. Parallelly, the masters’ review was also happening, and I ended up listening to all the juries there. A programme called ‘Theory in Design’ got me very interested. The process that was displayed, and what they were discussing got me interested in the programme and I decided to join that course.

PK: The two years I spent in the programme of Theory in Design was life changing and I think my practice has the most impact of what I learned through it. In the first semester, we were introduced to word ‘Paradox’. We were looking for paradox everywhere – in paintings, in books, in buildings, in any art-form. Later, they asked us to design a Prison and Rehabilitation Centre. We were new to these kinds of concepts, reading the theories first and trying to do it in the design. And we were looking for how the paradox can be achieved in a prison.

Some of my friends and I used to go to Adalaj Stepwell often. One day I was just sitting on one of the hanging bridges there and took pictures of people that are moving around at the bottom. Some of them were talking to their family, some were laughing with their friends, some were sitting with their partners, some kids were playing, and I was observing this. The idea that occurred to me was can we put a prisoner onto these hanging bridges so that he can constantly overlook to see what he is missing? That was a very crazy idea, but I thought why not do it, and I went straight to my mentors, Prof K B Jain and Prof Snehal Shah. They accepted the idea to see what kind of built form this will lead to. There, I came up with a barrier free cell as a paradoxical concept for a prison. I think that was the point where my belief systems changed; that how the out-of-the box concept has a power.

It was not me who had this idea; it was the methodology in which our mentors made us think. That was the miraculous thing that happened to me – that every time, the first thought I have is – let’s have a paradoxical idea for a project and then come down to a very functional thing.

[…] I have had an amazing time, best mentors and best bunch of people in CEPT. Very interestingly, the name of my firm has also come from my thesis project at the CEPT. I was doing research on generic essence and my mentors were Prof K B Jain and Prof Leo Peirera. The generic essence is about finding a gene into any creation. When you find a gene, you plant it or put it in another context. So that gene is going to get developed according to the surroundings, the conditions and the future requirements.

That made me realise that putting the idea first before architecture or before built form is extremely important and thus the name ‘Inception’ came to this.

PK: According to me, to develop good architecture, one requires good heart and thinking, rather than intelligence or a good mind. I am not saying that intelligence is not important, but I would like to quote what Roger Federer says in one of his interviews: “Yes, talent matters but talent has broad definitions, discipline is a talent, patience is a talent, trusting yourself is a talent, embracing the process and loving the process is a talent. Some people might be born with it, but others have to work for it.”

Similarly, in architecture, I think good intention to build is extremely important. What are we forming when we start the project? This intention has to be placed much before the thought of how the building will look like. This is an important intention we have to follow. We address it through a certain set of questions. We have not set those questions, but they arrive in many of our conversations.

We ask very prominently, ‘Is it necessary?’

When you ask this, ‘Are we building correct? Are we building unnecessarily? Are we not doing something which is not our aspiration?’ That is the first question.

Second is ‘Is it supporting and helping the larger surrounding?’ When you talk about the larger surrounding, you talk about the impact of your project on the context.

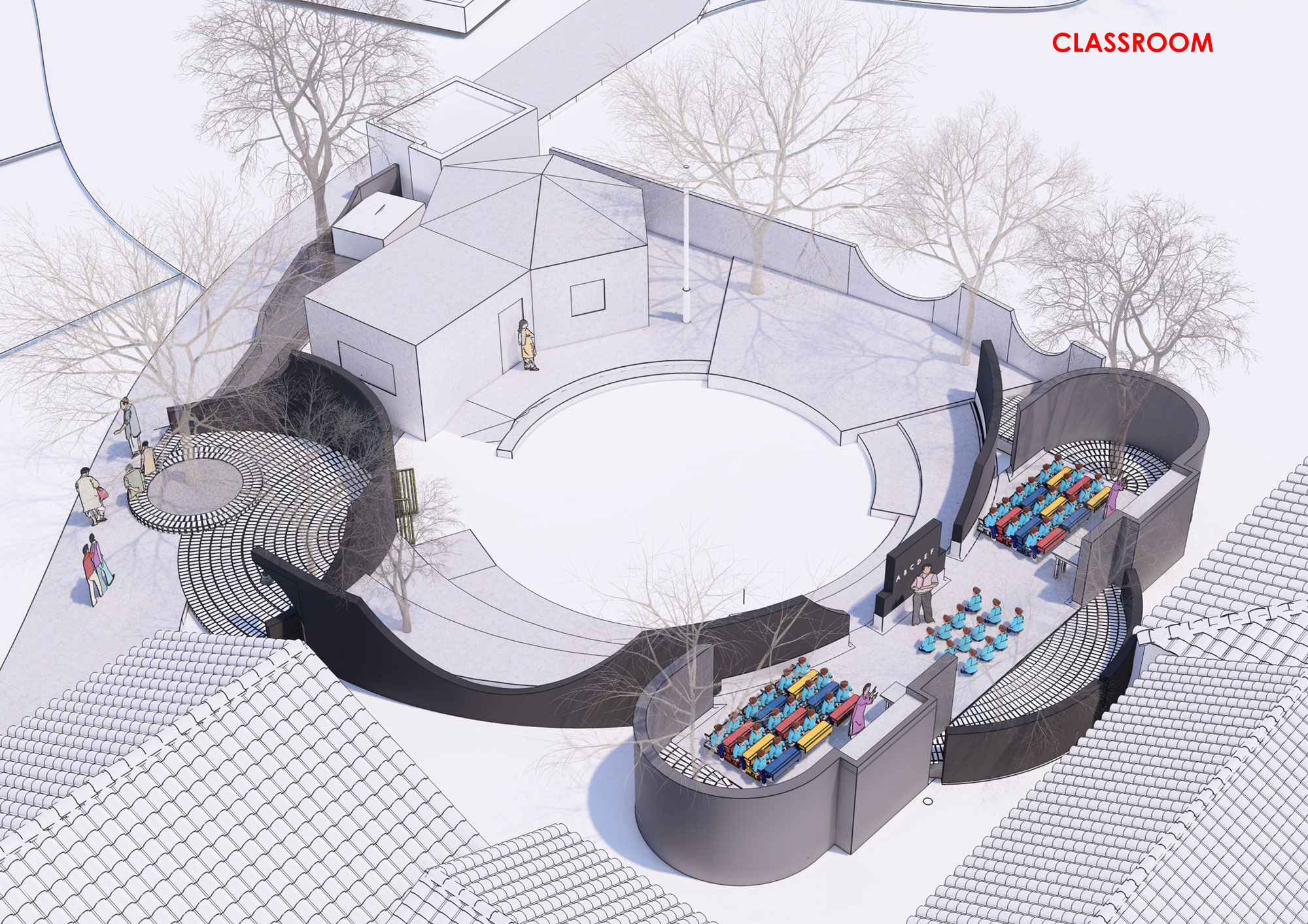

[…] One important question we ask many times is, ‘Is it a multifunctional space or is it an expandable space?’ In Indian tradition, I always feel that spaces should be modifiable. Those should be incremental, expandable, and accommodative in nature. We see to it that these questions are addressed in the central idea that we are trying to put in that project. We try to go as close as possible to respond this question.

Another very important factor is, we feel that our building should be very grounded and simple. It should reflect the ease of life, and not the glamour. For example, we work mostly with monochromatic, minimal colour and material palette, as I think that monochrome allows you to discover more. The simple and minimal approach allows one to experience the real essence of the space and that is important for us.

An important thing we look for as a practice is the greater agenda of the project. Is our building participating for the larger context. For that, we ask and deliberately discuss things like ‘Is our building talking to its neighbours? Is our building inclusive in nature? Where will the people meet? Where will they sit? Where will they celebrate?’

Lastly, this particular factor I wanted to share is, when we were designing House 20 by 22, the client wanted the house to be very secure and closed. We strategically made the folds in the walls and with the help of vertical openings, the house becomes inward looking while it is still connected. With this composition, it gets connected to the neighbours.

The only thing we realised is that this house does not look like one from the context. We had a lot of debate in our team, ‘do we have to reciprocate it to the context?’ This idea of contextualism, when we talk, we cannot forget that when you are thinking about the context, we also have to think that we are creating one, so we are more responsible towards what we are going to create. And that is why we stick to the idea, because our project was responding to the life, the way people are behaving.

CULTURE

<00:12:34>

PK: We are six to seven people working together, three to four architects, three to four trainees. We work like a team and there is no such hierarchy between us. Whenever any project comes, all of us sit together and discuss the project. Afterwards, everyone comes up with their ideas, puts them across the table, and we discuss it. That time it feels as though everybody is almost leading the project. It is not that I am a lead architect, and I have to give certain things, so everybody puts in their ideas, they feel equally responsible for that project, and they give a hundred percent to what they think about that. These ideas, we try to generate into a step further, we do not hold onto something that this idea has not been taken ahead. We try to see that all the ideas will be taken ahead.

What I really feel is, we actually work like a family; we laugh together and work together. For the projects which have come, everyone is equally passionate to make it more interesting. I strongly believe that the good and responsible work happens only when there is trust. Our entire team, we are like family members, we have lot of trust between each other. While choosing the team members we mostly see the intention and passion for architecture because I feel skill sets can be developed. We are fortunate to have the best team associated for pk_iNCEPTiON.

When a project comes, there is a process happening. There is the key idea of the project that you are making, transferring it into an actual built form. It requires a lot of deliberation, lots of discussion, lots of different perspectives, lots of revisions. That intensive process requires equally dedicated and passionate members, otherwise, I do not think it is possible to continuously do such rigorous process alone.

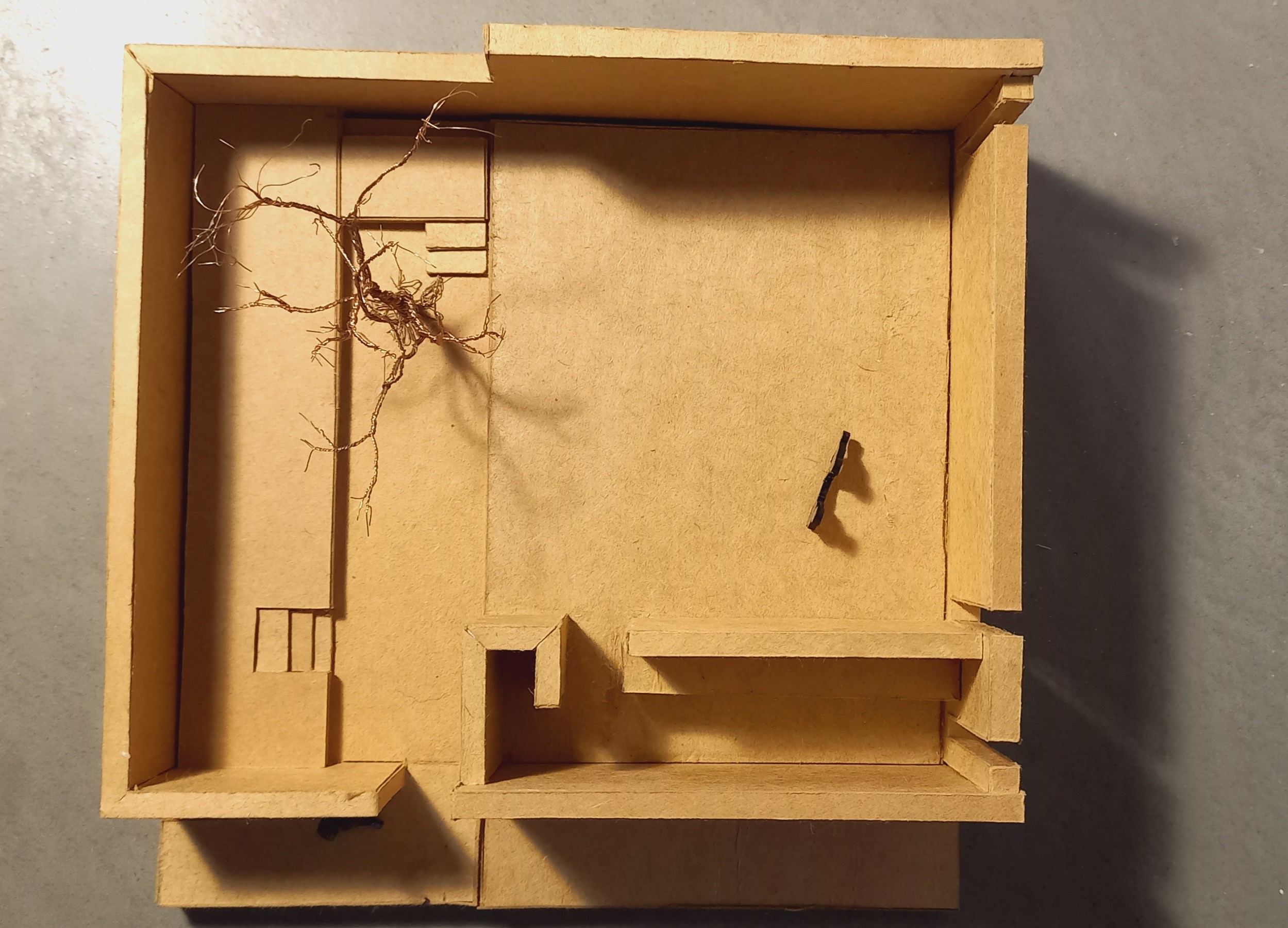

PK: The passionate approach and comprehensive thought process requires a best collaboration, so we also have people collaborate like our engineers, our contractors, all are a part of the team. ‘The Community Canvas’ project in a village. The contractor is from the village side. For him to understand, we give them a model where he would use the model to measure. My team member used to go to the village (we have setup of the office there on the site and everybody is actually working there like a worker). We try to associate with the people outside, so we ask the carpenter to come to the office, discuss the detailing with them. It is not that we are leading it, and we are giving the detail saying this is what you have to do.

This learning happens when this collaboration is very free. The hierarchy that I mentioned in the first place, is not only till the office but we see that the clients are also equally talking; ‘Let’s do this, let’s have it, can we walk and see to it.’ We go together to see the certain projects and experience and discuss it. This is how I think the collaboration happens in the office.

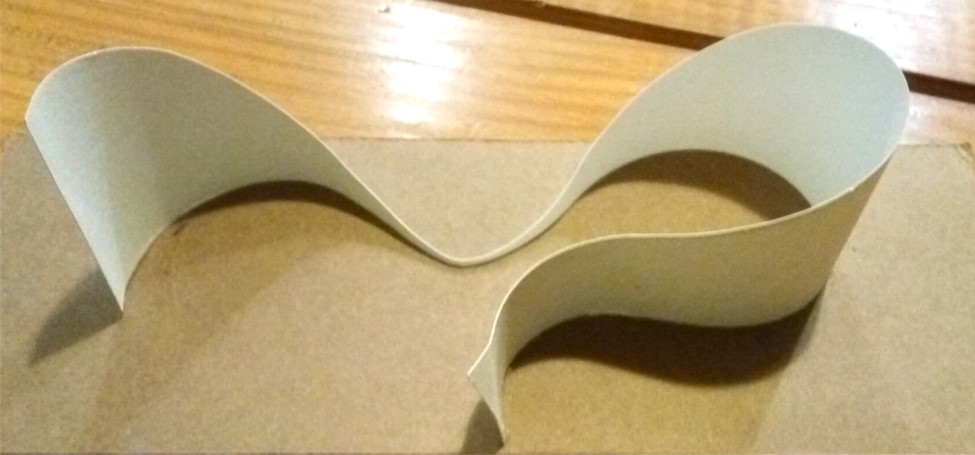

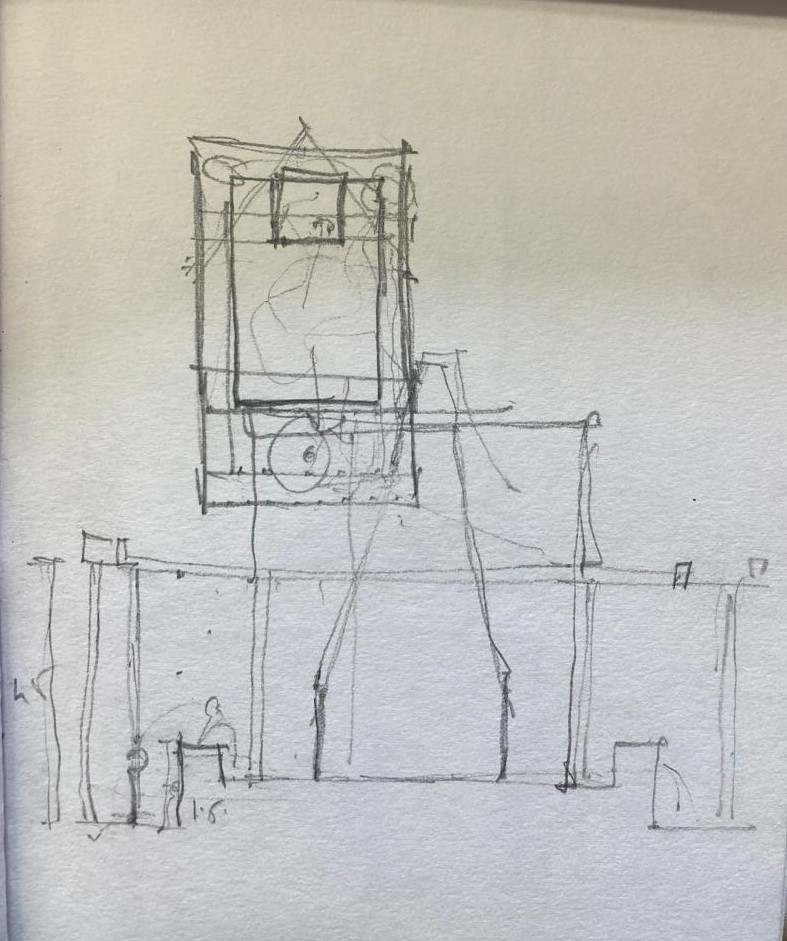

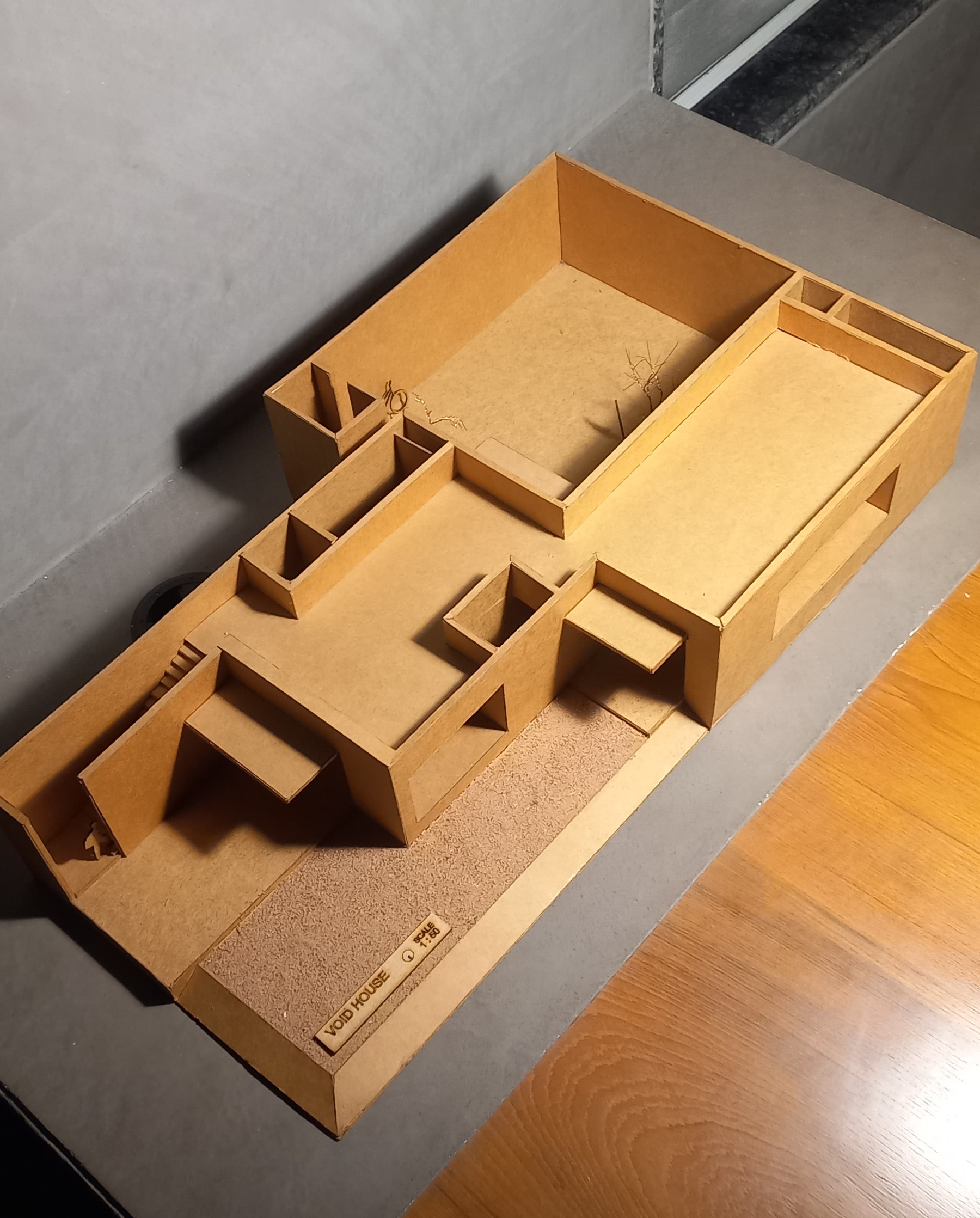

We make conceptual models of every idea; we do not think if the idea is well described or if it will be a good project. We generally start by making folly models – very conceptual models of every idea, whatever everybody has come up with. And then we sit together again and discuss about what the expression of that physical form of the model is telling us – whether it is conveying the idea of what it has been put into. Further, two to three ideas may be picked up, we think that it has more potential to develop further. Then we develop a better model where we think about the function and the placement of the spaces and the volumetric organisation.

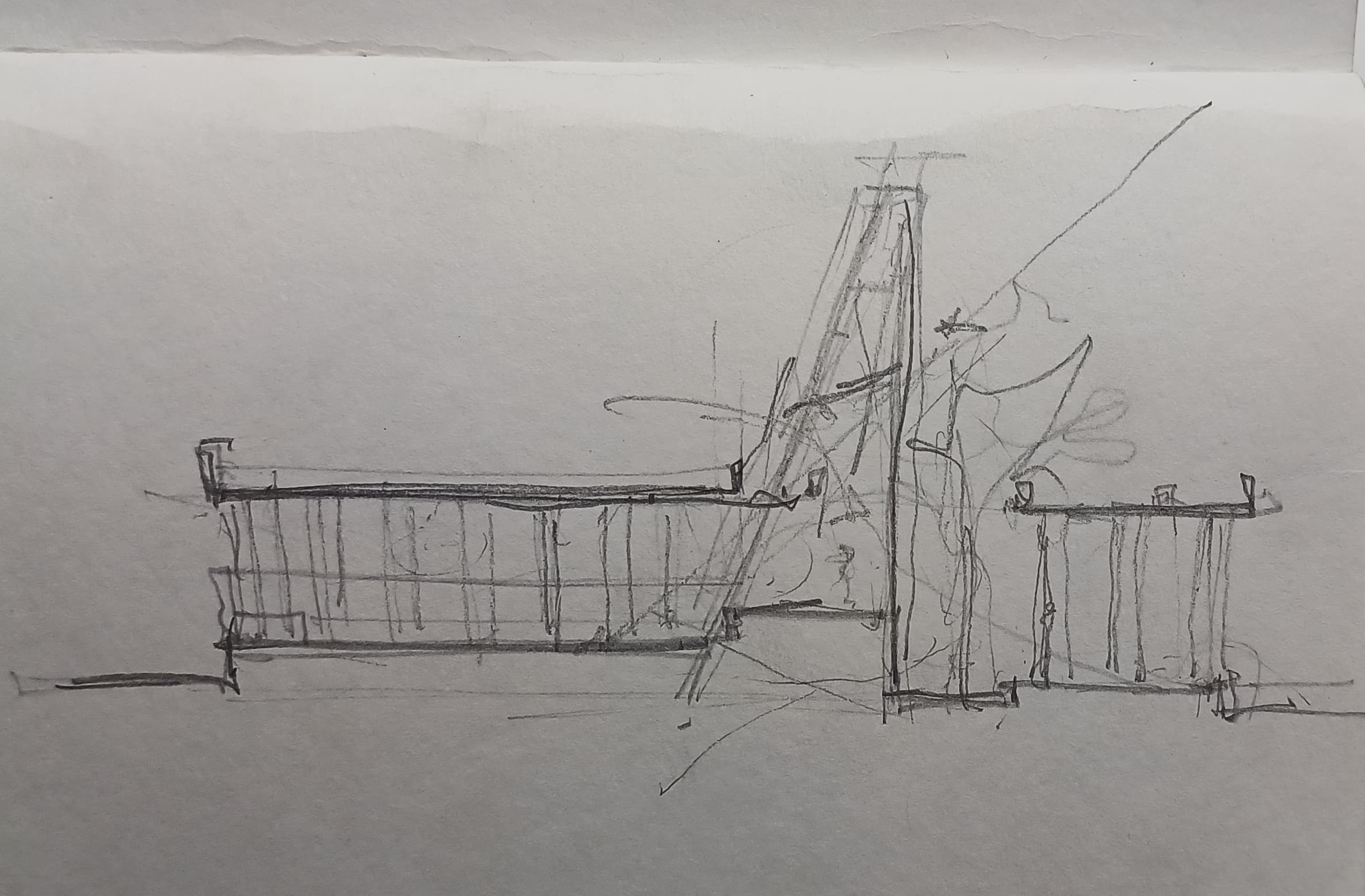

Those models then transfer into sketches. Generally, I sketch plans or a section. We develop a section first, so that the volume and the spaces have been crafted into it. Then we move to the plans. These drawings are then converted into drawings in the softwares. These set of drawings are converted into a bigger model of about 1:50 scale, something which we are comfortable with. Then we make a bigger model of that. That model then gives us a better idea of what we have started with. If the idea we had the first time, the core concept, is being reflecting or not. This process is very rigorous to do it. And this is how the team becomes important because everybody has a role. They have to do these revisions again and they are equally involved in the process.

PROCESS

<00:16:03>

PK: The typologies we are dealing with are mostly residential projects, the habitable spaces. Another important typology we have is educational typology where we are doing schools in an urban context as well as in the rural context. We are designing libraries and community spaces. Of course, there are a certain amount of commercial and residential interior projects also.

The scale of the projects have changed a lot nowadays.

The scale itself does not matter much. The idea we have to invest, takes equal energy for every project.

[…] We have also got a project where we design just a room called ‘anganwadi’. We have to design for Zilla Parishad. They wanted to have a prototype which can be repeated in 200 different places every year. That prototype requires a very universal approach because we do not know where it is going to be placed, how the context is. We had a very rigorous approach to the concept, making the project work as a universal idea. That took a lot of efforts, and a lot of ideas were invested. If we consider the scale, what I find is all the projects are equally exciting for us.

I think the opportunity to generate with any chance that comes your way makes the excitement for the project.

For example, this ongoing project, the ‘Hiwali School’ is located into the rural area, almost in the hilly side. It is a remote location, so the concept has also been developed similar to that. When the entire set of built expressions has been decided, how the space will behave and what kind of spaces will be designed, everything will be finalised. Then, we were looking for the material palette that would go with this concept. Because the material has to inform the context, it should inform how the users are going to use it, it should inform how it is going to last longer, because the maintenance becomes very difficult, reaching out there is very difficult. I just came across in one of my readings where Louis Kahn has spoken about ‘the idea of making structures as heritage, so can we really make our building look like ruins’, that was what I got out of it. Can we make our buildings look like ruins, where it looks like they have been there since long? It is not something new that has been coming up. The building should behave timeless in space and also the kind of aging the building is going to get.

Even before starting to think about what the actual architecture of the project would be, finding out an intent or having an enquiry for that particular programme is the prime focus for us. I always believe in the concept called ‘unsaid briefs’.

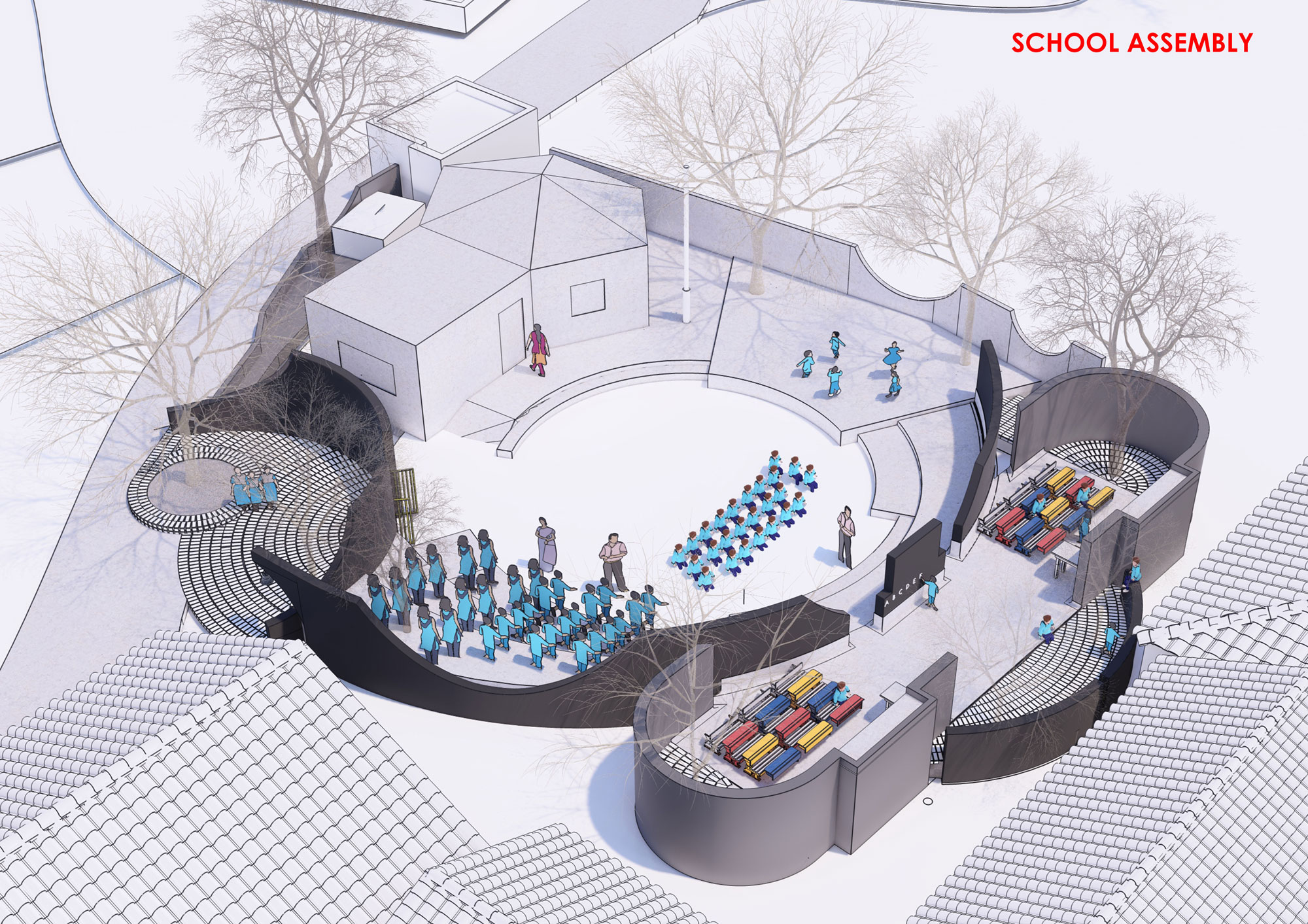

[…] To give an example of Community Canvas, the project was to design a compound wall and one classroom. We can call the typology of the project as a school. We were looking at a very free and open spaces, understanding how the kids will play. We developed a model which is very playful, which relates to these primary school kids. But COVID happened and I have seen how the villagers were suffering. There were no COVID centres, there were no extra facilities in the village where people can get space to have disaster management. For example, to celebrate something, to conduct marriages, to get together, to have public activities, the spaces to have this is missing from the village. These people do not even have the basic infrastructure. So, looking for something which is higher aspiration is difficult.

An idea that had come across was: can we make this project a community space? During daytime, it could run as a school, in the evening or in another time, it could be a social space or a public gathering space. It can be convertible; it can be made into a flexible space which can be converted into the hospital if needed. It can be converted into the visitor’s centre if needed. This is how the entire project has changed. I think that unsaid brief is what drove the entire project.

PK: In the cities, people are getting more and more private, and secluded by building very close to each other and in restrictive spaces. If you see the rural areas, spaces are more open and more humble in nature. But because of the concept of ‘Pakka Makan’, those people are also getting diluted. This way, the upcoming projects are coming towards rural areas.

I think it is the designer’s responsibility to make people aware of how the inclusive nature of architecture is important for everyone, it is not only for a particular project.

Slowly we are developing a city out of it. Even if you talk about a single project, can we talk and think about how the edge can be designed? Can we think about how the threshold has to be taken care of? Can it be of inclusive nature? When we are talking about privacy, we are not compromising on any of their aspiration but there are certain responsibilities that come with being a citizen or by staying in that area, by being part of a society. How our design is integrated is part of our project? Even if you are doing a commercial project or a private residence, we see to it that the compound wall belongs to both the sides and not just the house.

Another factor is to educate your clients. I always feel that designers should keep their personal aspirations and agendas aside. We should listen more to the client, if the client is coming with very irrelevant and temporary ideas, educate them, try to make them understand about how meaningful spaces will improve life for them. If whatever they are saying about the programme, if it is making any sense, then give your hundred percent to respond to what they are saying.

Very interestingly, when we were doing the school, everywhere we went, we used to take our models and go to site. Generally, in the school everybody participates, and the kids come, and they discuss about the project. Of course, their questions are very different than what we seek. One of the girls we had spoked to asked us, ‘can we climb on the wall?’ I reacted by saying, ‘No – you have floors, you have ramps where you can climb.’ But that question stuck with me. Why must she have asked this? While we were making the clay models in the office, we thought of these inverted arches where we sliced the walls in the shape of inverted arches and thought, ‘Yes, she can climb the walls now.’

Looking back, I think I did not find that question irrelevant. We responded to what she said. I am not saying every question is relevant but at least give it a thought and that is how you can accommodate everyone in the project. This is also I call a collaboration. She may be participating indirectly, but she participated, she made that project, she made those inverted arches that they are now climbing onto, that they are sliding onto.

PK: I have been following Louis I Kahn’s architecture since the very beginning of my practice. The inferences of what he says started coming into my projects when I started reading about him. This influence has come from my mentor, Prof K B Jain who worked with Louis Kahn. He used to tell us a lot of stories about how the design process for Louis Kahn would happen in their studio, what he woud talk about, what his perception is about a particular project, and then in the process when they used to make huge models and Louis Kahn used to sleep on the floor, take his head inside the model and see the light coming in and how the volume behaves. It was very inspiring to me.

Somewhere, after reading all this, looking at all the projects, and looking for the inferences has given me the concept called ‘Beyond Necessities’. Beyond necessities, for me, is to look beyond a function, it is to look for a higher aspiration of a client. Maybe they have not said about it, a higher aspiration of the surroundings is important for that. One of Louis Kahn’s quote says “When you make a building, you make a life, it comes out of the life. But when you only have the comprehension of a function of the building, it would not become an environment of a life”.

I also feel that we should go beyond a function. Of course, function is there, but what is that factor we are offering to make meaningful spaces better and how the concept of Beyond Necessities is important for us. How do we come to it?; it seems very philosophical to talk about. I have a very simple ways to do this, I ask my students, imagine a chair. What will their imagination be? Maybe four legs, a backrest, a chair with the hand rest or without a hand-rest, maybe with wheels or without wheels. There are certain aspects that comes in your head, but then when you ask them to imagine a seating – it can be a tree branch, it can be a stone, it can be a staircase, it can be a simple step, it can be a horizontal rod, it can be anything that can behave like a seating. I think when you change the vocabulary of your programme, we do not call it ‘a bedroom,’ we call them resting areas or sleeping areas. The bedroom focuses on putting the bed in front, so changing the vocabulary helps coming down to a better functional aspect. When we go to a volume or making a space, we also have the certain aspects for this. For example, this concept that I coined during my thesis project is Grey Spaces. The grey spaces if you see, is the white, black and grey spaces everywhere. White is of course open to the sky, grey is semi-covered, and black is which is completely covered space.

[…] Of course, we still have challenges when you come up with abstract things. Many times, we do not agree with a lot of ideas. We have done this house called Void House, which has also been published. There, we wanted to create a space for the family to come together. There is a lot of built crowd around. We wanted to make a secluded space for the family. So, we have built 30 feet x 33 feet of a courtyard, which goes up to 7 to 8 meters high. So initially, after looking at the models, they agreed to the concept. But when we were building the walls on site, the client came and saw the walls, and said that the walls are looking as if the space was a prison, and they asked us not to build such big walls.

At that point, we also questioned ourselves. But we were making a big decision for the project because we believed in something. So, we guaranteed them saying, let this be built. If they felt the same way after we had made it on the site, then it would be our responsibility to take it down. But for that you need to have a conviction on your idea. And that is how we try to see the challenges and that it can be solved without crossing anybody’s aspiration about their own space.

Being a teacher, it always takes you back to the time when you actually started asking a question, to a very initial phase.

I am involved in teaching for the last ten years, and I will not say that I was actually doing the teaching, but it was more like sharing with the students. Otherwise, every day you are coming to office, you are looking at your projects, discussing and trying to resolve something. But when we go to college, we go to that zone of discussing something with the students. I find freedom there. I find that we can discuss a lot of abstract ideas. We can bring up the paradox concept on the table. Students are curious. They are questions. We always see that they have a very different perspectives on many things.

That gives a lot of inferences for me to cross check my thought process. That helped develop me. Constantly being in teaching has evolved the thought process, it makes you read, it makes you have the patience, it develops the concept or the philosophy into very simple words. You have to be very expressive in asking somebody to imagine and then develop their own thought process. Another important thing is that I have been doing training since my third year. When I was a student, after college hours, I would go to one of our senior architects’ offices and work there. Whatever they are giving, even if it was a small drawing of a toilet, I would do it for about 10 – 12 days. I was doing it constantly. I was just observing what is happening in the office, how they would talk to the client, the complexities the team is having?

Our office has a similar system too. My teammates, almost all of them have been working since their second year with me. They are coming to the office, they are working three to four hours in the evening. They are equally participating in all the projects, and then they end up joining the team after graduating.

All of us, together, are getting developed.

CONTEXT

<00:45:20>

PK: I never thought about having any particular style. Not even now, we look like we are following certain things and of course, some of our projects may look like contemporary projects. But that is not something that has been informed deliberately. It may look contemporary, but the ideas come from history or the heritage or the origin of that particular context. For example, the ‘wadas’ of Nashik have these vertical windows. When you place the openings vertically, you have this cold wind coming inside from the lower part. Then you can have the four flaps and when you want to have privacy, you can close the lower two flaps. When you open up all of the four flaps, it becomes almost like a standing balcony. And that aspect you will see in two to three of our projects.

The House 20 x 22 is a vertical house. It is a complete cuboid, crafted with the white, folded walls. The vertical openings have come from the ‘wada’. Even the appearance of the verandas that we developed could be contemporary, but the sense of the place or the way we want the user to use it belongs to the historical way or to the traditional way of using it.

Regionalism is something we are really looking for. Bijoy Jain is one of the architects I look up to. I think he is one of the people who has expressed regionalism in a very strong format. He inspires me to look at the way he organises the things. The first time I went to Palmyra House, which is a place in Alibag, for a second I stopped breathing. That is mesmerising for me. How can somebody place two rectangles, perpendicular to the sea-facing view and still give the entire essence of the context when you enter inside? I think the amazing sense of composition and scale is what inspired me to follow Bijoy Jain.

My next inspiration would be the theories of Aldo Rossi. I read a lot of Aldo Rossi and Louis I Kahn. Aldo Rossi has designed one project. The project is not built. It is called a Cuneo monument. That monument has been a memorial for the soldiers who have given their life in war against the Nazis. In this simple cuboid, there is a steep flight of steps and there is this landing, which is almost compressing that space. This shows the burden on the soldier when you are actually climbing it, and once you finish climbing, you open up into the open-to-sky courtyard which expresses freedom. This theory has been manifested into a simple cube that inspires me. […]

For us, belonging to the context, responding to the futuristic need, making it more usable, expandable so that it can be convertible and to look timeless. That is the contemporariness for me and that is how I look. A very famous quote by Jan Gehl which I follow a lot is where he says,

“First life, then spaces, then buildings.

The other way around never works”

And that is the end line for whatever we try do in our practice.

Images and Drawings: © pk_iNCEPTiON

Filming: SBFlix Visuals; Sagar Bondarde

Editing: Gasper D’souza, White Brick Post Studio

PRAXIS is editorially positioned as a survey of contemporary practices in India, with a particular emphasis on the principles of practice, the structure of its processes, and the challenges it is rooted in. The focus is on firms whose span of work has committed to advancing specific alignments and has matured, over the course of the last decade. Through discussions on the different trajectories that the featured practices have adopted, the intent is to foreground a larger conversation on how the model of a studio is evolving in the context of India. It aims to unpack the contents, systems that organise the thinking in a practice.

The third phase of PRAXIS focuses on experimental vectors of practice and explorative models that support thought-provoking ideas and architectural processes.

Praxis is an editorial project by Matter in partnership with Şişecam Flat Glass.